News

Newswise —

Few threats to public health are as perilous as cigarette smoking, with more than 435,000 Americans dying each year of tobacco-related pulmonary illnesses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD ranks as the third-leading cause of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality worldwide in 2012 and the global cost of illness related to COPD is expected to rise to $4.8 trillion by 2030, yet there are currently no effective medical treatments to cure COPD or stop its progression.

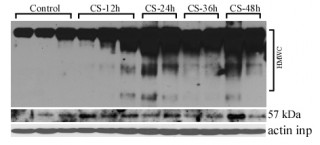

Since the identification of factors contributing to the development of COPD is crucial for developing new treatments, a team of scientists including Anna Blumental-Perry, PhD, from the department of surgery, and Xing-Huang Gao, PhD, from the department of genetics and genome sciences, at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine embarked on a study to examine COPD development at the cellular level. Specifically, Blumental-Perry and her team sought to better understand the mechanisms of a relatively new scientific concept – the smoke induced collapse of protein homeostasis and its contribution to age-dependent onset of COPD. Knowing that upon inhalation of cigarette smoke (CS), the free radicals in it can reach the interior of lung cells where they react with a wide variety of cell proteins and affect their functions, the scientists formed the hypothesis that CS-free radicals can interfere with proper folding of the proteins within the cell.

The scientists’ findings, recently published in The Journal of Biological Chemistry, demonstrated that free radicals—small, unstable molecules present in CS—can reach the endoplasmic reticulum, a cellular organelle that is critical in manufacturing and transporting fats, steroids, hormones and various proteins, and alter its function by oxidizing and damaging its most abundant and crucial to protein folding chaperone, Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI).

Determining that PDI is a critical factor in the development of COPD, the researchers identified for the first time how cells adapt to the presence of less functional PDI, which is by increasing the levels of it through a novel mechanism at the protein synthesis level, as opposed to the level of gene transcription. Since adaptation wears off with age, the researchers have now identified one of the first clues to age-dependency in COPD onset.

“Understanding the mechanisms of the collapse of protein homeostasis in COPD allows us to focus on maintaining functional levels of PDI. This could improve outcomes for the many patients with COPD as well as potentially giving us clues to improve health with aging.” said Blumental-Perry. “We discovered that PDI is a critical new factor in the pathogenesis of COPD, and that protein collapse in COPD is age dependent and unpredictable. Based on these fascinating findings, we plan to conduct future research targeting failed adaptive systems in an effort to maintain functional levels of PDI, and prevent it from acquisitions of ‘bad’ functions – discoveries that could ultimately help us to identify new therapeutic approaches for COPD.”

This research was supported by Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute Young Clinical Investigator Award 092207; National Institute of Health grants 5P20GM103542 from the National Center for Research Resources; COBRE in Oxidants, Redox Balance and Stress Signaling; CO6 RR015455; R37-DK60596 and R01-DK53307.

For more information about Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, please visit: case.edu/medicine.

Newswise —

Researchers at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles have identified a new genetic candidate for testing therapies that might affect fear learning in people with PTSD or other conditions. Results of the study have been published in theJournal of Neuroscience.

Individuals with trauma- and stress-related disorders can manifest symptoms of these conditions in a variety of ways. Genetic risk factors for these and other psychiatric disorders have been established but do not explain the diversity of symptoms seen in the clinic – why are some individuals affected more severely than others and why do some respond better than others to the same treatment?

“People often experience stress and anxiety symptoms, yet they don’t usually manifest to the degree that results in a clinical diagnosis,” says Allison T. Knoll, PhD, post-doctoral fellow at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “We felt that if we could understand differences in the severity of symptoms in a typical population, it might provide clues about clinical heterogeneity in patients.”

The strategy was simple. Instead of focusing on a single gene identified for a given condition, the team at CHLA tried a different approach to discover genes that may impact symptom severity. Using a population-based mouse model, they studied normal variation in how well the mice detected threats and fears. They used mice that are well-characterized for learning behavior, and also exhibit a wide range of “high” and “low” anxiety, modeling the range found in humans. The investigators tested to see how well the mice learned to detect threats, a form of fear learning that all humans and animals do. When this learning is exaggerated in children or adults, symptoms of PTSD and anxiety are expressed.

“By understanding the biological origins of individual behavioral differences – in this case a measure of anxiety – we can move beyond a single disorder diagnosis and treat the dimensions that produce a behavior spanning a multitude of diagnoses,” said Knoll.

Newswise — Using genetic tools, the researchers found a number of candidate genes that might influence learning of fear, and ultimately narrowed down to a single gene, Hcn1. The researchers were able to further demonstrate the impact of the Hcn1 gene on fear learning by interfering with the function of this gene before the learning challenge. They found that the mice did not learn fear. Even when the researchers disrupted gene function after the mice learned the fear, the mice were unable to express it.

“We’re suggesting that instead of focusing only on the genes that are thought to cause a disorder – for example, PTSD or anxiety disorder – it is important to discover those genes that can have a profound effect on how severely an individual is impacted by their disorder,” said Pat Levitt, PhD, Principal Investigator of the study, and the Simms/Mann Chair in Developmental Neurogenetics at CHLA. Levitt is also provost professor of Pediatrics, Neuroscience, Psychiatry and Pharmacy at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Newswise — COLUMBUS, Ohio –

In a surprising twist, benign brain tumors that have previously been tied to obesity and diabetes are less likely to emerge in those with high blood sugar, new research has found.

The discovery could shed light on the development of meningiomas, tumors arising from the brain and spinal cord that are usually not cancerous but that can require risky surgery and affect a patient’s quality of life.

Because previous research had established that the slow-growing tumors are more common among people who are obese and those who have diabetes, researchers led by The Ohio State University’s Judith Schwartzbaum set out to look for a relationship between meningiomas and blood markers, including glucose.

After all, high blood sugar is a component of diabetes and a precursor to its development. Furthermore, Type 2 diabetes and obesity are closely linked.

But when they compared blood tests in a group of more than 41,000 Swedes with meningioma diagnoses 15 or fewer years later, they found that high blood sugar, particularly in women, actually meant the person was less likely to face a brain tumor diagnosis.

“It’s so unexpected. Usually diabetes and high blood sugar raises the risk of cancer, and it’s the opposite here,” said Schwartzbaum, an associate professor of epidemiology and a researcher in Ohio State’s Comprehensive Cancer Center. The work appears this month in the British Journal of Cancer.

“It should lead to a better understanding of what’s causing these tumors and what can be done to prevent them.”

Though meningiomas are rarely cancerous, they behave in a similar way, leading scientists to wonder if some relationships between possible risk factors and tumor development would be similar, Schwartzbaum said.

The researchers, looking at data collected from 1985 to 2012, identified 296 cases of meningioma, more than 61 percent of them in women.

Women with the highest fasting blood sugar were less than half as likely as those with the lowest readings to develop a tumor.

The relationship was not statistically significant when researchers looked at men’s fasting sugar readings and tumor development.

But when they compared the less-reliable non-fasting sugar readings (those taken without a period of no food or drink that could influence the results), they found that both men and women with high blood sugar had a lower likelihood of meningioma diagnosis.

A diabetes diagnosis before meningioma also appeared to decrease the risk of this tumor, although Schwartzbaum said the data likely had incomplete information on diabetes.

The results could lead to a clearer explanation of how the tumors develop and grow and could potentially start researchers down the road to improved diagnostic techniques, Schwartzbaum said.

“These tumors take years to develop, and an earlier diagnosis would certainly lead to better surgical outcomes,” she said.

About seven in 100,000 U.S. residents receive a meningioma diagnosis annually. Meningiomas can cause headaches, weakness in the limbs, seizures, vision problems and personality changes. They represent about a third of all tumors that originate in the brain, according to the American Brain Tumor Association.

Possible explanations for the relationship could be found by closer examination of the role of sex hormones and the interplay between glucose levels and those hormones, Schwartzbaum said. It’s also possible that sugar levels dip during early tumor development because the tumor is using glucose to grow, she said.

“There are so many things still to be learned, but I am glad that people are now serious about studying these so-called benign tumors,” Schwartzbaum said.

Because information in the database is limited, the researchers weren’t able to account for all the confounding factors that could have contributed to their results, including body mass index, blood pressure and hormone levels.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

Schwartzbaum’s collaborators at Ohio State were Brittany Bernardo, Robert Orellana, and Yiska Lowenberg Weisband. Others who worked on the study at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden were Niklas Hammer, Goran Walldius, Hakan Malmstrom, Anders Ahlbom and Maria Feychting.

#

Newswise —

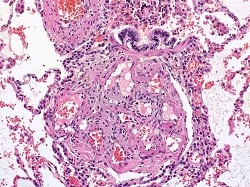

Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers report that rising blood levels of a protein called hematoma derived growth factor (HDGF) are linked to the increasing severity of pulmonary arterial hypertension, a form of damaging high blood pressure in the lungs. Their findings, described online June 2 in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, could, they say, eventually lead to a more specific, noninvasive test for pulmonary arterial hypertension that could help doctors decide the best treatment for the disease.

“This has the potential to be a much more specific readout for the health of the lungs than what we currently measure using invasive cardiac catheterization,” says senior study author Allen Everett, M.D., professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Proteome Center at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “It could really have value in making decisions about when to escalate therapy and when to ease it because at present, it’s difficult to determine whether someone’s disease is getting better or worse, especially in children.”

High blood pressure in the arteries that lead from the heart to the lungs is distinct from the most common forms of high blood pressure and can be difficult to diagnose, with shortness of breath frequently being the first or only symptom. Pulmonary hypertension is more common in women. Unlike many other forms of high blood pressure, the cause of pulmonary arterial hypertension isn’t always clear, but it can be genetic and/or associated with HIV and other infections, congenital heart disease, connective tissue disorders and living at high altitude. It often appears in otherwise healthy young people.

While there’s no cure for pulmonary arterial hypertension — which is estimated to affect 200,000 Americans — there are an increasing number of drugs available to help relax the arteries in the lungs, and lung transplants are a last-resort therapy.

Hoping to change the uncertainty surrounding diagnosis and therapy, Everett and his colleagues developed a new test to measure levels of HDGF in blood, which, Everett says, is a growth factor protein important for the formation of new blood vessels in the lung — a process known to readily occur in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. His research group compared blood samples from 39 patients with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension who had failed treatment for pulmonary arterial hypertension and were waiting for lung transplants, and a control group of 39 age, gender and race-matched healthy volunteers. They found median protein levels were about seven times higher than in controls, with a median of 1.93 nanograms per milliliter in patients and a median of 0.29 nanograms per milliliter in the controls.

When the team followed up the new observation with blood tests of HDGF levels in an additional 73 patients over five years, the results were dramatic, Everett says. Patients with an HDGF level greater than 0.7 nanograms per milliliter had more extensive heart failure and walked shorter distances in a six-minute walking test. HDGF was also lower in survivors than nonsurvivors (0.2 nanograms per millilieter versus 1.4 nanograms per milliliter), with elevated levels associated with a 4.5-fold increased risk of death even after adjusting for age, pulmonary hypertension type, heart function and levels of a protein that in the blood that predicts heart failure. These findings, Everett says, suggest that HDGF has a distinct advantage to current clinical measures for predicting survival in patients with pulmonary hypertension. This kind of “dose response” information is critical to demonstrate in preliminary, proof-of-principle research, he says.

Although the biochemical details of why there is a link between pulmonary arterial hypertension and HDGF remain unknown, Everett suspects levels of the growth factor might increase to spur blood vessel healing when arteries stretch in the lungs due to pulmonary arterial hypertension. HDGF is unique to current clinical measures of pulmonary hypertension, as it does not come from the heart and reflects more specifically how the disease affects the lungs, he says.

Cautioning that the new findings need further examination and confirmation, Everett nevertheless says his team’s early results already point toward the value of using levels of HDGF in diagnosing and tracking pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults. “This could be a cheap and easy way to say: ‘Oh, good, your levels are going down. Let’s try to take away one of your medicines and see how that works,’” he explains. “Or if you know from the very beginning of their treatment that someone isn’t responding to any medicines, you can get them on the list for a lung transplant much sooner.”

More research is needed to reveal whether levels change as drug therapy eases symptoms during the course of a disease, whether the results hold true in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension and whether HDGF can be used to predict patients at risk of developing pulmonary arterial hypertension in the future.

Drug treatment is designed to thin the blood, relax arterial walls, and dilate or open up blood vessels. People with pulmonary arterial hypertension also can benefit from oxygen therapy and surgery to reduce pressure on the right side of the heart. Treatments are complicated and carry numerous serious side effects, Everett says, so finding measures that allow clinicians to minimize drug therapy will reduce side effects and cost.

In addition to Everett, the study’s authors are Jun Yang, Melanie Nies, Zongming Fu, Rachel Damico, Frederick Korley and Paul Hassoun of The Johns Hopkins University; Ivy Dunbar of the University of Colorado; and Eric Austin of Vanderbilt University.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant numbers 1R03HL110830-01, R24HL123767, P50 HL084946/R01 and HL114910); the Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association.

Newswise —

Poor physical fitness and sedentary behaviour are linked to increased pain conditions in children as young as 6-8 years old, according to the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children Study ongoing at the University of Eastern Finland. The findings were published in the Journal of Pain.

The study analysed the association of physical fitness, exercise, physically passive hobbies and body fat content with various pain conditions in 439 children. Out of individual pain conditions, physically unfit children suffered from headaches more frequently than others. High amounts of screen time and other sedentary behaviour were also associated with increased prevalence of pain conditions.

Pain experienced in childhood and adolescence often persists later in life. This is why it is important to prevent chronic pain, recognise the related risk factors and address them early on. Physical fitness in childhood and introducing pause exercises to the hobbies of physically passive children could prevent the development of pain conditions.

The Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) Study carried out by the Institute of Biomedicine at the University of Eastern Finland generates extensive and scientifically valuable public health data on children's lifestyle habits, health and well-being.

###

Newswise — RIVERSIDE, Calif. –

A team of sleep researchers at the University of California, Riverside, led by psychology professor Sara C. Mednick, has found that the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for control of bodily functions not consciously directed (such as breathing, heartbeat, and digestive processes) plays a role in promoting memory consolidation – the process of converting information from short-term to long-term memory – during sleep.

The groundbreaking study, “Autonomic Activity During Sleep Predicts Memory Consolidation in Humans,” appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Mednick and her team demonstrated, for the first time, that increases in autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity during sleep is correlated with memory improvement.

“Sleep has been shown to facilitate the transformation of recent experiences into long-term, stable memories,” explained Mednick. “But, past studies produced contradictory evidence about which specific sleep features enhance memory performance.” According to Mednick, this suggests that there may be unidentified events during sleep that play an important role in this process. Because memory during waking hours is enhanced by ANS activity, Mednick tested whether the ANS could be the missing link that explains how sleep promotes memory consolidation.

To test this idea, Mednick and the team of researchers added a memory component to a well-known creativity test called the Remote Associates Test (RAT). In between two RAT testing sessions, they gave people a nap and measured the quality of sleep and heart activity.

In the first part of the study, 81 healthy individuals were presented with RAT problems consisting of three seemingly unrelated words (e.g., cookies, sixteen, heart) and were required to find another word (e.g., sweet) that links the three words together. Some participants were also asked to complete an unrelated analogy task. The answers to the analogy task served as primes for solving some of the problems in the second RAT test that occurred after the nap. After completing these tasks, 60 of the participants took a 90-minute nap, while the remaining subjects watched a video. Later in the day, all the participants returned to the lab and completed RAT problems for a second time. The problems were either identical to the previous test (repeated condition), completely new (novel condition) or had the same answers as the analogy task (primed condition).

Individuals who had a nap were more likely to answer the creativity problems in the afternoon with words that were primed by the morning analogies task compared with people who didn’t nap. In other words, a nap helped the experimental subjects think more flexibly and combine primed words in “new and useful” combinations. Importantly, while approximately 40 percent of the performance improvement due to the nap could be predicted by the amount of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, when the researchers considered heart rate activity during REM, they could account for up to 73 percent of the performance increases.

“The findings suggest that ANS activity during REM sleep may be an unexplored contributor to sleep-related improvements in memory performance.” said Mednick. These results have implications for understanding the mind/body connection and relationships between sleep, cardiovascular health and cognitive functioning.

Newswise — BIRMINGHAM, Ala. –

Women live longer than men.

This simple statement holds a tantalizing riddle that Steven Austad, Ph.D., and Kathleen Fischer, Ph.D., of the University of Alabama at Birmingham explore in a perspective piece published in Cell Metabolism on June 14.

“Humans are the only species in which one sex is known to have a ubiquitous survival advantage,” the UAB researchers write in their research review covering a multitude of species. “Indeed, the sex difference in longevity may be one of the most robust features of human biology.”

Though other species, from roundworms and fruit flies to a spectrum of mammals, show lifespan differences that may favor one sex in certain studies, contradictory studies with different diets, mating patterns or environmental conditions often flip that advantage to the other sex. With humans, however, it appears to be all females all the time.

“We don’t know why women live longer,” said Austad, distinguished professor and chair of the UAB Department of Biology in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences. “It’s amazing that it hasn’t become a stronger focus of research in human biology.”

Evidence of the longer lifespans for women includes:• The Human Mortality Database, which has complete lifespan tables for men and women from 38 countries that go back as far as 1751 for Sweden and 1816 for France. “Given this high data quality, it is impressive that for all 38 countries for every year in the database, female life expectancy at birth exceeds male life expectancy,” write Austad and Fischer, a research assistant professor of biology.• A lifelong advantage. Longer female survival expectancy is seen across the lifespan, at early life (birth to 5 years old) and at age 50. It is also seen at the end of life, where Gerontology Research Group data for the oldest of the old show that women make up 90 percent of the supercentenarians, those who live to 110 years of age or longer.• The birth cohorts from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s for Iceland. This small, genetically homogenous country — which was beset by catastrophes such as famine, flooding, volcanic eruptions and disease epidemics — provides a particularly vivid example of female survival, Austad and Fischer say. Over that time, “life expectancy at birth fell to as low as 21 years during catastrophes and rose to as high as 69 years during good times,” they write. “Yet in every year, regardless of food availability or pestilence, women at the beginning of life and near its end survived better than men.”• Resistance to most of the major causes of death. “Of the 15 top causes of death in the United States in 2013, women died at a lower age-adjusted rate of 13 of them, including all of the top six causes,” they write. “For one cause, stroke, there was no sex bias, and for one other, Alzheimer’s disease, women were more at risk.”

Cell Metabolism invited Austad to contribute this perspective paper, “Sex differences in lifespan.”

Austad first became interested in the topic when Georgetown University asked him to lecture on it in 2003. Although lab models like the roundworm C. elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the mouse Mus musculus are intensively used in scientific studies, people in those fields are not very aware of how longevity patterns by sex can vary according to genetic backgrounds, or by differences in diet, housing or mating conditions, Austad says.

Those uncontrolled variables lead to different results in longevity research. A survey of 118 studies of laboratory mice by Austad and colleagues in 2011 found that 65 studies reported that males outlived females, 51 found that females outlived males, and two showed no sex difference.

But if variables are carefully controlled, mice may prove to be a useful model to study sex differences in the cellular and molecular physiology of aging, Austad and Fischer write.

This understanding will be helpful as researchers start to develop drugs for human use that affect aging, Austad says. “We may be able to develop better approaches,” he said. “There is some complicated biology underlying sex differences that we need to work on.”

Differences may be due to hormones, perhaps as early as the surge in testosterone during male sexual differentiation in the uterus. Longevity may also relate to immune system differences, responses to oxidative stress, mitochondrial fitness or even the fact that men have one X chromosome (and one Y), while women have two X chromosomes.

But the female advantage has a thorn.

“One of the most puzzling aspects of human sex difference biology,” write Austad and Fischer, “something that has no known equivalent in other species, is that for all their robustness relative to men in terms of survival, women on average appear to be in poorer health than men through adult life.”

This higher prevalence of physical limitations in later life is seen not only in Western societies, they say, but also for women in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, Thailand and Tunisia.

One intriguing explanation for this mortality-morbidity paradox is a possible connection with health problems that appear in later life. Women are more prone to joint and bone problems, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and back pain, than are men. Back and joint pain tends to be more severe in women, and this could mean chronic sleep deprivation and stress. Thus, the sex differences in morbidity could be due to connective tissue maladies in women, and connective tissue in humans is known to respond to female sex hormones.

But this is just one of several plausible hypotheses for the mystery of why women live longer, on average, than men.

Newswise — Washington, DC —

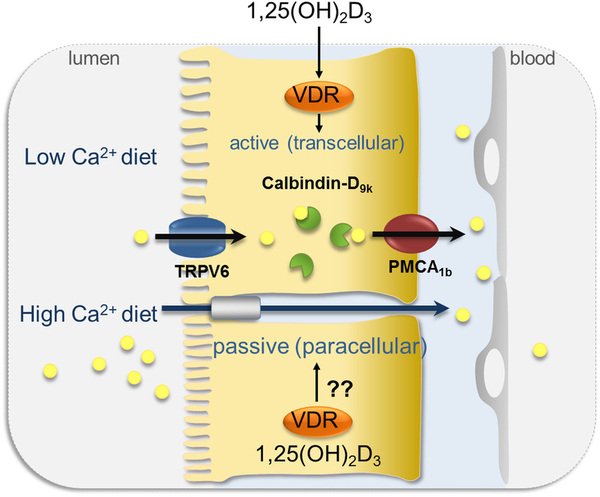

Measuring intestinal calcium absorption may help to identify individuals who are prone to develop kidney stones, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology(CJASN).

Individuals with hypercalciuria have kidneys that put out higher levels of calcium in urine than normal, which increases their risk of developing kidney stones. Only a portion of hypercalciuric individuals will develop stones, however, and there are no criteria to distinguish them from those who remain free of stones.

To look for such distinguishing factors, Giuseppe Vezzoli, MD (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, in Milan, Italy) and his colleagues evaluated absorption of calcium in the first part of the small intestine as well as urinary excretion of calcium in 172 hypercalciuric stone formers and 36 hypercalciuric patients without a history of kidney stones.

The researchers found that both absorption and excretion of calcium were faster in hypercalciuric stone formers than in hypercalciuric patients without a history of stones.

“To our knowledge this is the first study comparing calcium metabolism in hypercalciuric patients with or without calcium stones,” said Dr. Vezzoli. “Its findings identify a characteristic of calcium metabolism that may predispose hypercalciuric patients to calcium stone formation, and highlight the role of intestinal absorption in stone formation.”

Study co-authors include Lorenza Macrina, MD, Alessandro Rubinacci, MD, Donatella Spotti, MD, and Teresa Arcidiacono, MD.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research and from the San Raffaele Scientific Institute.

The article, entitled “Intestinal calcium absorption among hypercalciuric patients with or without calcium kidney stones will appear online athttp://www.cjasn.asnjournals.org/ on June 9, 2016, doi:10.2215/CJN.10360915.

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of The American Society of Nephrology (ASN). Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s). ASN does not offer medical advice. All content in ASN publications is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to cover all possible uses, directions, precautions, drug interactions, or adverse effects. This content should not be used during a medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. Please consult your doctor or other qualified health care provider if you have any questions about a medical condition, or before taking any drug, changing your diet or commencing or discontinuing any course of treatment. Do not ignore or delay obtaining professional medical advice because of information accessed through ASN. Call 911 or your doctor for all medical emergencies.Founded in 1966, and with nearly 16,000 members, the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) leads the fight against kidney disease by educating health professionals, sharing new knowledge, advancing research, and advocating the highest quality care for patients.# # #

Newswise —

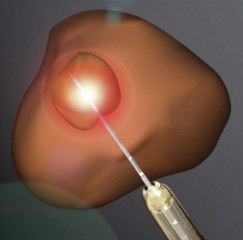

Prostate cancer patients may soon have a new option to treat their disease: laser heat. UCLA researchers have found that focal laser ablation – the precise application of heat via laser to a tumor – is both feasible and safe in men with intermediate risk prostate cancer.

The Phase 1 study, published June 10 in the peer-reviewed Journal of Urology, found no serious adverse effects or changes in urinary or sexual function six months after the procedure. The technique uses magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, to guide the insertion of a laser fiber into cancerous tumors. When heated, the laser destroys the cancerous tissue.

A follow-up study, presented in a poster presentation at the American Urology Association meeting in May, showed the potential to transfer this treatment for the first time into a clinic setting, using a special device (Artemis) that combines both MRI and ultrasound for real-time imaging. The Artemis device arrived at UCLA in 2009. Since then, 2000 image-fusion biopsies have been performed – the most in the U.S. - and this large experience has paved the way for treatment to be done in the same way.

If the laser technique, known as MRI-guided focal laser ablation, proves effective in further studies -- especially using the new MRI-ultrasound fusion machine -- it could improve treatment options and outcomes for men treated for such cancers, said study senior author Dr. Leonard Marks, a professor of urology and director of the UCLA Active Surveillance Program. Historically, prostate cancer has been treated with surgery and radiation, which can result in serious side effects such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

“Our feeling was that if you can see prostate cancer using the fusion MRI and can put a needle in the spot to biopsy it, why not stick a laser fiber in the tumor the same way to kill it,” Marks said. “This is akin to a lumpectomy for breast cancer. Instead of removing the whole organ, target just the cancer inside it. What we are doing with prostate cancer now is like using a sledgehammer to kill a flea.”

Up until now, capturing an image of a prostate cancer has been difficult because prostate tissue and tumor tissue are so similar. Precise, non-invasive surgical treatment has proved difficult as a result.

As the Journal of Urology study shows, however, MRI improves the ability of physicians to perform precise, laser-based treatment. The new fusion-imaging method improves it even further, providing real-time ultrasound that more clearly delineates the tumor. By combining laser ablation with this fusion-imaging technique, the potential of laser ablation grows enormously.

Previous research at UCLA has demonstrated the value of using the same fusion imaging technique to perform biopsies to diagnose prostate cancers in men with rising PSA who had multiple negative conventional biopsies. Such biopsies are usually “blind,” meaning physicians take a tissue sample based on what they believe is the location of a possible tumor.

The new Journal of Urology study provides proof of principle that laser ablation can be done safely and effectively with MRI. In this case, eight men underwent ablation while in an MRI machine. Although none had serious side effects, longer-term follow-up is needed, as is a continued assessment of appropriate treatment margins to ensure cure, the researchers said.

The second study tested the fusion-MRI procedure on 11 men in a clinical setting. That study found the procedure was well -tolerated under local anesthesia and resulted in no side effects. At four months follow-up, there were no changes in urinary or sexual function.

“This focal therapy provides a middle ground for men to choose between radical prostatectomy and active surveillance, between doing nothing and losing the prostate,” Marks said. “This is a new and exciting concept for prostate cancer treatment.”

The laser treatment is not yet approved for use in prostate cancer by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“I think we were so successful in this effort because of the experience we gained doing the targeted biopsies,” Marks said. “That allowed us to go from biopsy to treatment.”

The studies were funded through private philanthropy and by a grant from Medtronic.

For more than 50 years, the urology specialists at UCLA have continued to break new ground and set the standards of care for patients suffering from urological conditions. In collaboration with research scientists, UCLA’s internationally renowned physicians are pioneering new, less invasive methods of delivering care that are more effective and less costly. UCLA’s is one of only a handful of urology programs in the country that offer kidney and pancreas transplantation. In July of 2015, UCLA Urology was ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. For more information, visit http://www.urology.ucla.edu/.

Newswise — DENVER –

Twenty to 50 percent of Americans suffer from acute insomnia each year, defined as difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, three or more nights per week, for between two weeks and three months. Roughly 10 percent of Americans experience chronic insomnia lasting longer than three months. The effects of chronic insomnia (and/or sleep loss) include impaired physical and mental performance, increased risk for mental health disorders (such as, depression and substance abuse), and increased risk for medical diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

Now, preliminary findings from a Penn Medicine study (abstract #0508) presented at SLEEP 2016, the 30th annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC, suggest that what may prevent 70 to 80 percent of individuals with new onset insomnia (acute insomnia) from developing chronic insomnia is a natural tendency to self-restrict time in bed (TIB). For example, if someone goes to sleep at 11 p.m. and wakes up at 5 a.m. (versus an intended 7:30 a.m.), they start their day, rather than lie awake in bed.

Electing to stay awake (rather than staying in bed trying to sleep) is not only a productive strategy for an individual with acute insomnia, but is also one that is formally deployed as part of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia.

Last month, the American College of Physicians recommended Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as the initial, first-line treatment for chronic insomnia, based on data showing the therapy can improve symptoms without the side effects associated with sleep drugs.

By evaluating over a year how time in bed varies in 416 individuals who remain good sleepers (GS), in good sleepers who begin suffering from acute insomnia and then recover (GS-AI-REC), and in good sleepers who transition to acute insomnia and then to long-term chronic insomnia (GS-AI-CI), the study provides the first evidence supporting the significant role that sleep extension – the effort to recover lost sleep by increasing one’s sleep opportunity, or TIB – plays in turning acute insomnia into chronic insomnia. The results from these preliminary data analyses show that 20 percent of the population of good sleepers experience acute insomnia per year, 45 percent of these individuals recover, 48 percent have persistent but periodic insomnia, and 7 percent develop chronic insomnia.

“Those with insomnia typically extend their sleep opportunity,” says Michael Perlis, PhD, an associate professor in Psychiatry and director of the Penn Behavioral Sleep Medicine Program. “They go to bed early, get out of bed late, and they nap. While this seems a reasonable thing to do, and may well be in the short term, the problem in the longer term is it creates a mismatch between the individual’s current sleep ability and their current sleep opportunity; this fuels insomnia.”

The findings offer the first data confirming a theory (the 3P model of insomnia) developed by the late Arthur Spielman in the 1980s, that says the catalyst for the transition from acute to chronic insomnia is “sleep extension,” that is, the tendency to expand sleep opportunity to make up for sleep loss.

Echoing Spielman, Perlis says, “Acute insomnia is likely a natural part of the human condition. If you think about the fight flight response, as trigger for sleeplessness, this makes sense. That is, it shouldn’t matter that it’s 3 a.m. and you’ve been awake for the last 22 hours, if you’re being threatened and you believe there is a threat to your quality of life or existence, it’s not a good time to sleep. It is understandable that sleeplessness has persisted as an adaptive response to such circumstances. In contrast, it’s hard to imagine how chronic insomnia is anything but bad…and the clinical research data support this position given chronic insomnia’s association with increased medical and psychiatric morbidity.”

Co-authors on the study include Ellis J. of the Northumbria Center for Sleep Research (United Kingdom), Knashawn H. Morales from Penn, Michael Grandner of the University of Arizona, and Charles Corbitt, Genevieve Nesom , and Waliuddin Khader from Penn. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01AG041783) and the Economic Social Research Council (RES-061-25-0120-A).

Perlis will present the team’s findings at SLEEP on Wednesday June 15, 2016 at 9:30 am in room 605.

###Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania(founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $5.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 18 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $373 million awarded in the 2015 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center -- which are recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report -- Chester County Hospital; Lancaster General Health; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2015, Penn Medicine provided $253.3 million to benefit our community.