News

Newswise — DALLAS – April 10, 2017 – UT Southwestern Medical Center pediatric researchers have harnessed an analytical tool used to predict the weather to evaluate the effectiveness of therapies to reduce brain injury in newborns who suffer oxygen deprivation during birth.

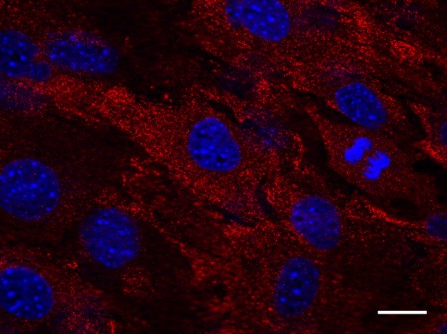

The analytical tool, called wavelet analysis technology, is best known for predicting long-term weather patterns, such as El Nino. UT Southwestern researchers say this same analytical tool can help improve assessment and treatment of newborns with asphyxia, which is when the baby’s brain is deprived of oxygen due to complications during birth. The non-invasive method produces real-time heat maps of the infant’s brain that doctors can use to determine whether therapies to prevent brain damage are effective.

“These are babies to whom something catastrophic happened at birth. What this technology does is measure physiologic parameters of the brain – blood flow and nerve cell activity – to produce a real-time image of what we are calling ‘neurovascular coupling.’ If there is high coherence between these two variables, you know that things are going well,” said Dr. Lina Chalak, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at UT Southwestern and lead author of the study.

The wavelet analysis correlates information from two non-invasive technologies that are currently used on a day-to-day basis in neonatal intensive care: amplitude EEG and near infrared spectroscopy. The approach combines the results from these commonly done tests in a sophisticated way and creates a new proxy measure of brain health called neurovascular coupling. When neuronal activity and brain perfusion are synchronized – as indicated by large areas of red on heat maps created by this method – treatment is working well.

About 12,000 newborns experience oxygen deprivation (asphyxia) during birth in the U.S. each year, according to a 2010 article in Lancet. This can occur for a number of reasons, such as the cord being wrapped around the baby’s neck, a difficult breech birth, or the separation of the placenta from the uterus too soon, Dr. Chalak explained. These infants are at high risk of developing serious consequences such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and cognitive deficits.

No treatments were available until about 10 years ago when a national study in which UT Southwestern participated, showed that reducing the baby’s core temperature could counteract the impact of birth asphyxia for some infants. The cooling blankets are now standard treatment, but only about half of babies treated with a cooling blanket benefit.

Until the adaptation of the wavelet technology, doctors couldn’t determine which infants were benefitting from cooling treatment and which babies may need additional therapies, which are being developed.

Wavelet analysis information also can help in evaluation of new therapies. Dr. Chalak plans to use wavelet analysis as part of the HEAL study, a large clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of erythropoietin, a hormone that promotes the formation of red blood cells, to treat newborns with asphyxia. Wavelet analysis will be used to evaluate infants who are part of the HEAL study at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, Parkland Hospital, and Children’s Medical Center.

Wavelet technology also may help determine which children should be treated.

“Of the babies who are oxygen-deprived, some don’t qualify for cooling because their brain damage or encephalopathy is judged to be mild. Yet some of these children have adverse outcomes. This technology may help us identify who needs cooling,” said Dr. Rashmin Savani, Chief of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine and Professor of Pediatrics and of Integrative Biology, who holds The William Buchanan Chair in Pediatrics.

It could also lead to other discoveries.

“Understanding of brain blood flow regulation and its impact on brain function in newborns with asphyxia using this novel technology has great potential for developing new sensitive biomarkers for clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for these sick babies, which is desperately needed in the field,” said co-author Dr. Rong Zhang, Associate Professor of Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, and of Internal Medicine, and a member of the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at UT Southwestern.

The research appears in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

Other UT Southwestern researchers who contributed to this paper are Dr. Beverley Adams-Huet, Assistant Professor of Clinical Sciences and of Internal Medicine; Diana Vasil, research nurse; and Dr. Takashi Tarumi, Instructor in Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, along with Dr. Fenghua Tian, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at UT Arlington. The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Chalak said the new tools represent a paradigm shift for physicians who treat oxygen-deprived newborns. “Hopefully, the future will be bright for babies who suffered asphyxia, differing from the bleak prognoses of the past.”

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution’s faculty has received six Nobel Prizes, and includes 22 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 18 members of the National Academy of Medicine, and 14 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. The faculty of more than 2,700 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide care in about 80 specialties to more than 100,000 hospitalized patients, 600,000 emergency room cases, and oversee approximately 2.2 million outpatient visits a year.

###

Newswise —

A 5K fun run shouldn’t involve more physical preparation than major surgery, but that’s the disconnect Michael Englesbe, M.D., sees all too often.

Just as an athlete might work to build up stamina before a race, a person entering the hospital also can benefit from prepping the mind and body. Even minor adjustments to diet and mental health could help some individuals go home sooner — and, in turn, save hospitals and insurance companies money.

But for many health care providers, that concept isn’t always put into practice.

“We do a lot in medicine to get people ready for surgery, but they’re primarily administrative tasks — checking off boxes that don’t necessarily make a patient better,” says Englesbe, a Michigan Medicine transplant surgeon who has studied and championed the idea for nearly a decade.

“The more you can do to manage your status preoperatively, the quicker you’ll be able to bounce back.”

In February, Englesbe, colleague Stewart Wang, M.D., Ph.D., FACS, and several other authors confirmed their longtime hunch: A study published in Surgery found that basic fitness and wellness coaching, administered in advance, could reduce a surgical patient’s average hospital stay two days, from seven down to five, when compared to a control group.

And, in a benefit to patients and providers alike, the regimen cut medical costs 30 percent.

Moreover, the participation rate among the study’s 641 subjects was high — about 80 percent, far better adherence than what might follow a typical medical appointment.

“As a physician, you always tell people to quit smoking and exercise,” says Englesbe, “but the compliance rates are notoriously abysmal.”

The prospect of serious surgery, he notes, can be a change agent in itself: “Big health crises can scare people straight, so to speak, and change their lifestyle.”

Still, the researchers say, promoting healthful habits in advance of an operation is a measure that should be just as crucial as any other step in the admittance process.

Adds Wang: “The condition of the body is so important. It’s so much common sense that people often fail to recognize it.”

A virtual coach

The recent study marks the third time Englesbe and Wang have examined the idea of athletic training applied to surgical preparation, which they call “prehab.” Hospitalization times and cost savings were consistent among the analyses.

Each review followed the Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP), an initiative aimed at helping patients target and strengthen weaknesses before surgery. A web-based risk assessment tool using a person’s existing data enables shared decision-making between patient and physician and helps identify patients who will best benefit from MSHOP.

Elements of the program include improving one’s diet, reducing stress, breathing exercises and smoking cessation, and, most crucial, an emphasis on light physical activity — with the latter reinforced via daily notifications.

Most MSHOP patients are advised to log 12 miles of walking per week, or about an hour a day. Each participant is given a pedometer to track progress.

It sounds simple, but it can pay off: Walking aids blood flow and speeds healing.

“The vast majority of the program benefits come from the walking,” says Wang, endowed professor of burn surgery and director of the Morphomic Analysis Group at Michigan Medicine.

Early MSHOP efforts encouraging patients to boost their steps involved personal phone calls, a method ultimately revised due to staffing requirements and, given the demands of patients’ work and personal lives, subpar reach.

The system now relies on automated daily text messages or automated phone calls to deliver a reminder. Program facilitators worked to craft notes with positive, natural-sounding language to make the exchanges personal and more effective.

That way, “the patient feels like someone is actually paying attention to them,” says June Sullivan, the technology director for MSHOP, noting that any replies are monitored and logged.

“And, they respond with things like ‘This is a great program’ or ‘Sorry I didn’t do well today — I’ll try harder.’”

Training to win

If surgeries were races, the procedures MSHOP patients received — liver, gastrointestinal, pancreas and thoracic surgery; organ transplant; and esophageal resection, among other operations — might be likened more to triathlons than turkey trots.

“They were pretty big operations,” Englesbe says.

Because the analyzed cases were elective, as about 90 percent of all surgeries in the United States are, the notion of prehab based on the study’s findings could spur some doctors to more carefully evaluate a patient’s readiness (and perhaps delay plans if warranted).

“Surgery is basically controlled injury,” says Wang, whose background is in trauma medicine. “You’re ‘whacking’ patients and hoping that in the end they do better overall because you’ve interrupted the disease process.”

No matter the circumstance, be it a car crash or a kidney transplant, a patient’s strength can dictate their path going forward.

People with weak psoas muscles, for instance, “did terribly after surgery,” Wang says of the findings that led to the creation of MSHOP.

And MSHOP components can not only boost physical healing, but also provide emotional benefits in the days before the procedure — and, ideally, beyond.

“Patients don’t care about costs or how long they’re going to be in the hospital; they just want to get through the experience,” Englesbe says. “This is an empowering tool that helps them do something positive in the face of a very negative event.”

Growing the franchise

Since its establishment five years ago, the MSHOP curriculum is now offered in more than 20 hospitals and 30 practices across Michigan.

Despite plenty of positive feedback and proof of prehab’s benefits, the practice encompasses just a sliver — about 1,250 patients — of the 65,000 surgeries performed annually at Michigan Medicine.

Debate about logistics and wider implementation also remain among medical professionals.

“First, we hear that everyone thinks it makes sense for their patients,” says Englesbe. “Second, it’s really hard to change clinical practice, especially among busy surgeons. It’s essentially adding work to the busiest people.”

Although the cost benefits are notable, that factor doesn’t necessarily register with clinicians, the researchers note. And, says Sullivan, the technology director, surgeons must be the ones to start the dialogue: “They have to deliver the message; that’s who the patient believes.”

Still, the MSHOP movement has caught the attention of insurance payers that might be able to help facilitate a wider reach.

“Once it’s a billable service, it will really take off,” Englesbe says.

Because current prehab guidelines are somewhat general, there also is room to grow.

They could one day be tailored to address more specific scenarios, such as prescribing certain exercises prior to a joint replacement surgery.

“The technology is scalable,” Wang says. “Expected complications or recovery difficulties could be addressed in advance with targeted training. This is just the beginning.”

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

Researchers in Germany have developed a transgenic mouse that could help scientists identify new influenza virus strains with the potential to cause a global pandemic. The mouse is described in a study, “In vivo evasion of MxA by avian influenza viruses requires human signature in the viral nucleoprotein,” that will be published April 10 in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Influenza A viruses can cause devastating pandemics when they are transmitted to humans from pigs, birds, or other animal species. To cross the species barrier and establish themselves in the human population, influenza strains must acquire mutations that allow them to evade components of the human immune system, including, perhaps, the innate immune protein MxA. This protein can protect cultured human cells from avian influenza viruses but is ineffective against strains that have acquired the ability to infect humans.

To investigate whether MxA provides a similar barrier to cross-species infection in vivo, Peter Staeheli and colleagues at the Institute of Virology, Medical Center University of Freiburg, created transgenic mice that express human, rather than mouse, MxA. Similar to the results obtained with cultured human cells, the transgenic mice were resistant to avian influenza viruses but susceptible to flu viruses of human origin.

MxA is thought to target influenza A by binding to the nucleoprotein that encapsulates the virus’ genome, and mutations in this nucleoprotein have been linked to the virus’ ability to infect human cells. Staeheli and colleagues found that an avian influenza virus engineered to contain these mutations was able to infect and cause disease in the transgenic mice expressing human MxA.

MxA is therefore a barrier against cross-species influenza A infection, but one that the virus can evade through a few mutations in its nucleoprotein. Staeheli and colleagues think that their transgenic mice could help monitor the potential dangers of emerging viral strains. “Our MxA-transgenic mouse can readily distinguish between MxA-sensitive influenza virus strains and virus strains that can evade MxA restriction and, consequently, possess a high pandemic potential in humans,” Staeheli says. “Such analyses could complement current risk assessment strategies of emerging influenza viruses, including viral genome sequencing and screening for alterations in known viral virulence genes.”

Deeg et al., 2017. J. Exp. Med. http://jem.rupress.org.cgi/doi/10.1084/jem.20161033?PR

# # #

Newswise — ANN ARBOR, Mich. –

Researchers at Michigan Medicine have found the livers of patients with a rare disease that affects metabolism have responded positively to leptin therapy.

In an open-label study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, the research team predicted the response of 23 patients with partial lipodystrophy-associated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (fatty liver) to metreleptin, a man-made version of the naturally occurring hormone leptin, which regulates fat and glucose metabolism.

The researchers reported patients with a lower baseline leptin level had a higher response rate after one year of treatment with metreleptin, a pharmaceutical produced by Novelion Therapeutics’ subsidiary. They presented their findings today at ENDO 2017, the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society, in Orlando, Florida.

Lipodystrophy is a group of rare diseases that share in common the selective loss of fat tissue from the body. Patients affected by the diseases generally have severe insulin resistance, high lipids in their blood and fatty liver. The condition highlights how important fat cells are to regulating a person’s metabolism.

Generalized lipodystrophy results in fat loss throughout the entire body. Partial lipodystrophy results in fat loss typically in the arms, legs, head and torso, and fat accumulation in the neck, face and intra-abdominal areas of the body. Metreleptin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014 to treat generalized lipodystrophy, but has not been approved to treat partial lipodystrophy.

“Fatty liver, or excess fat building up in the liver, is a common metabolic disturbance seen in patients with lipodystrophy,” says Elif Oral, M.D., associate professor of endocrinology at Michigan Medicine and principal investigator of the study. “The underlying metabolic disturbances seen in this patient population can be difficult to manage with traditional therapies.”

The partial lipodystrophy study participants underwent two liver biopsies, one at the beginning of the trial and after one year of treatment. Investigators observed their NASH score, a numerical score for progression of fatty liver disease in patients, and their NAS score, a numerical score for progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Of the 23 patients enrolled in the study, 22 were treated with at least one dose of metreleptin at baseline. Of the 18 patients who completed treatment after one year, NASH scores improved from a mean of 6 at baseline (showing moderate to advanced disease) to a mean of 5. NAS scores also improved from a mean of 5 at baseline to a mean of 4 after 12 months of treatment.

The researchers noted that these changes were statistically significant in the patient group.

“About half of the patients had scores that lowered by two points or more, which is clinically significant in patients with this disease,” says Oral. “Generally, that type of drop is only seen with 10 percent or more sustained weight loss in the common form of fatty liver disease, which usually only occurs with metabolic surgery.”

Patients that experienced the two-point or greater reduction improvement in their scores from treatment had a lower baseline leptin level of 14.5 ng/mL versus non-responders whose average leptin level at baseline was 25 ng/mL.

In addition, some patients saw reductions in glucose control and lipid levels, but the differences noted in the entire cohort did not attain statistical significance. The most frequently reported adverse events in the study, occurring in more than 20 percent of the patients, were upper respiratory infections, hypoglycemia and diarrhea.

“The liver disease at baseline is quite significant among the patients in this study, which showed a significant degree of inflammation and fibrosis, even in the absence of liver test abnormalities,” says Nevin Ajluni, M.D., assistant professor of endocrinology at Michigan Medicine and the presenting author of the study. “This highlights the importance of screening for this complication.”

About lipodystrophy research at Michigan Medicine

The Michigan Medicine Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes, and the Brehm Center for Diabetes Research collectively host a major referral center for the study of lipodystrophy syndromes. The Division houses a clinical program to deliver state-of-the-art care for atypical forms of diabetes that aims to improve the lives of patients afflicted with these unusual diseases. The program also supports discovery research for uncovering new disease mechanisms and possible new drugs for these disorders. For more information, contact Adam Neidert at (734) 615-0539.

About Michigan Medicine

At Michigan Medicine, we create the future of healthcare through the discovery of new knowledge for the benefit of patients and society; educate the next generation of physicians, health professionals and scientists; and serve the health needs of our citizens. We pursue excellence every day in our three hospitals, 40 outpatient locations and home care operations that handle more than 2.1 million outpatient visits a year. The U-M Medical School is one of the nation’s biomedical research powerhouses, with total research funding of more than $470 million. For more information, please visit: www.michiganmedicine.org.

Newswise — BIRMINGHAM, Ala. –

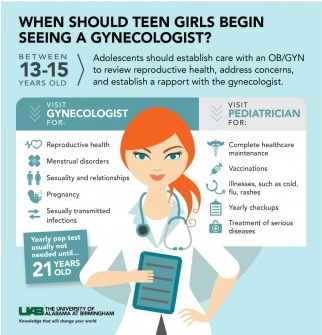

For a parent of a girl, it is important to teach proper health care practices. Part of this is maintaining proper gynecological and reproductive care upon puberty. Two major questions that come up in regard to an adolescent’s seeing a gynecologist are when and why.

“Having an open conversation with your daughter about her overall health is important at any age,” said Janeen Arbuckle, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatric obstetrician and gynecologist in the University of Alabama at Birmingham Division of Women’s Reproductive Healthcare. “We provide gynecological care to girls from birth to age 21.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that adolescents establish care with an OB/GYN between the ages of 13 and 15. This visit serves primarily as an opportunity for the adolescent to review her reproductive health, address any concerns she may have and establish a rapport with the gynecologist. Depending on her individual needs, she may then be seen periodically by the gynecologist.

“Timing can always be addressed with your child’s pediatrician,” Arbuckle said. “An adolescent should receive care from both pediatricians and gynecologists. Parents can help reassure their adolescent that her pediatrician and gynecologist work in collaboration to assure her overall health.”

A pediatrician provides more complete health care maintenance, while the gynecologist focuses on the reproductive health of the patient. Adolescents are often referred by their pediatricians to an OB/GYN for the evaluation and management of menstrual disorders, concerns regarding reproductive anatomy or for the initiation of contraception.

Gynecologists often address sensitive and private information with their patients, which is kept confidential. As the adolescent ages, she may elect to maintain her relationship with her gynecologist.

Common reasons for patients to pursue care with a gynecologist are concerns regarding pubertal development, abnormal periods, vaginal discharge and sexual behavior.

An important part of gynecological health is having a yearly Pap test. This is not typically necessary until age 21. However, an adolescent could see a gynecologist to address issues she may not be comfortable discussing with her parents or pediatrician, ensuring that her overall health is intact, including periods, sexuality and relationships, pregnancy, and sexual transmitted diseases.

OB/GYNs can help a young woman’s overall health by maintaining a healthy body weight and encouraging confidence in her body, identifying healthy habits for healthy bones, addressing urinary tract infections, and offering treatment for vaginal itch, discharge or odor.

Puberty brings on many unanswered and embarrassing questions for an adolescent. Seeing an OB/GYN provides a platform to talk about what is normal versus abnormal, including pain, flow of periods, cycle length, bleeding in between periods and ways to deal with premenstrual syndrome.

Another uncomfortable conversation for adolescents as their bodies are changing is sexuality and relationships. An OB/GYN can evaluate relationships with a boyfriend or girlfriend and know if these relationships are threatening or harmful. They can also talk about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender topics.

“Most importantly, we can help an adolescent think things through before an adolescent has sex for the first time,” Arbuckle said. “Knowing the challenges and risks ahead of time could help an adolescent in the future. We can address emotional stress, safe sex, and the potential for an unwanted pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections.”

Adolescents should be informed when it comes to pregnancy — from conversations on why the adolescent should be on birth control to planning ahead for a safe, healthy pregnancy, to knowing what to do if you become pregnant.

“It is important that adolescents know how to prevent pregnancy, but also how to handle it if they do become pregnant,” Arbuckle said. “They should know when and how to test for pregnancy, as well as what their options are should they become pregnant.”

Additional dangers of being sexual active are sexually transmitted infections. An adolescent should be educated on the types of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus that can become contracted when one is sexually active. By using the proper protection, the risk of becoming infected can be significantly reduced.

An OB/GYN can help determine if the human papillomavirus vaccine is appropriate for a young woman based on her sexual activity.

“If adolescents are sexually active, they should know the risks and should get tested for STIs and HIV,” Arbuckle said. “Our job as an OB/GYN is to inform patients of the risks of being sexually active with multiple partners, but also provide resources for adolescents to protect themselves, while being a confidante and protecting their privacy.”

Depending on their insurance, they may require a referral from their pediatrician. It is helpful but not required for the patient’s medical records to be available for review at the time of her first visit. These can either be brought with the patient at the time of the visit or faxed to the office by the referring physician.

Newswise — ORLANDO—

Insufficient sleep, a common problem that has been linked to chronic disease risk, might also be an unrecognized risk factor for bone loss. Results of a new study will be presented Saturday at the Endocrine Society’s 99th annual meeting in Orlando, Fla.

The study investigators found that healthy men had reduced levels of a marker of bone formation in their blood after three weeks of cumulative sleep restriction and circadian disruption, similar to that seen in jet lag or shift work, while a biological marker of bone resorption, or breakdown, was unchanged.

“This altered bone balance creates a potential bone loss window that could lead to osteoporosis and bone fractures,” lead investigator Christine Swanson, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Colorado in Aurora, Colo., said. Swanson completed the research while she was a fellow at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Ore., with Drs. Eric S. Orwoll and Steven A. Shea.

“If chronic sleep disturbance is identified as a new risk factor for osteoporosis, it could help explain why there is no clear cause for osteoporosis in the approximately 50 percent of the estimated 54 million Americans with low bone mass or osteoporosis,” Swanson said.

Inadequate sleep is also prevalent, affecting more than 25 percent of the U.S. population occasionally and 10 percent frequently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report.

The 10 men in this study were part of a larger study that some of Swanson’s co-authors conducted in 2012 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Mass. That study evaluated health consequences of sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Swanson defined circadian disruption as “a mismatch between your internal body clock and the environment caused by living on a shorter or longer day than 24 hours.”

Study subjects stayed in a lab, where for three weeks they went to sleep each day four hours later than the prior day, resulting in a 28-hour “day.” Swanson likened this change to “flying four time zones west every day for three weeks.” The men were allowed to sleep only 5.6 hours per 24-hour period, since short sleep is also common for night and shift workers. While awake, the men ate the same amounts of calories and nutrients throughout the study. Blood samples were obtained at baseline and again after the three weeks of sleep manipulation for measurement of bone biomarkers. Six of the men were ages 20 to 27, and the other four were ages 55 to 65. Limited funding prevented the examination of serum from the women in this study initially, but the group plans to investigate sex differences in the sleep-bone relationship in subsequent studies.

After three weeks, all men had significantly reduced levels of a bone formation marker called P1NP compared with baseline, the researchers reported. This decline was greater for the younger men than the older men: a 27 percent versus 18 percent decrease. She added that levels of the bone resorption marker CTX remained unchanged, an indication that old bone could break down without new bone being formed.

“These data suggest that sleep disruption may be most detrimental to bone metabolism earlier in life, when bone growth and accrual are crucial for long-term skeletal health,” she said. “Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to explore if there are differences in women.”

This study received funding from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute on Aging and the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon.# # #

Newswise —

Genetic testing of tumor and blood fluid samples from people with and without one of the most aggressive forms of skin cancer has shown that two new blood tests can reliably detect previously unidentifiable forms of the disease.

Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center and its Perlmutter Cancer Center, who led the study, say having quick and accurate monitoring tools for all types of metastatic melanoma, the medical term for the disease, may make it easier for physicians to detect early signs of cancer recurrence.

The new blood tests, which take only 48 hours, were developed in conjunction with Bio-Rad Laboratories in Hercules, Calif. Currently, the tests are only available for research purposes.

The new tools are the first, say the study authors, to identify melanoma DNA in the blood of patients whose cancer is spreading and who lack defects in either the BRAF or NRAS genes, already known to drive cancer growth. Together, BRAF and NRAS mutations account for over half of the 50,000 cases of melanoma diagnosed each year in the United States, and each can be found by existing tests. But the research team estimates that when the new tests become available for use in clinics, the vast majority of all melanomas will be detectable.

“Our goal is to use these tests to make more informed treatment decisions and, specifically, to identify as early as possible when a treatment has stopped working, cancer growth has resumed, and the patient needs to switch therapy,” says senior study investigator and dermatologist David Polsky, MD, PhD.

Polsky presents his team’s latest findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research on April 2 in Washington, D.C.

The new tests, says Polsky, the Alfred W. Kopf, MD, Professor of Dermatologic Oncology at NYU Langone and director of its pigmented lesion section in the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, monitor blood levels of DNA fragments, known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), that are released into the blood when tumor cells die and break apart. Specifically, the test detects evidence of changes in the chemical building blocks (or mutations) of a gene that controls telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), a protein that helps cancer cells maintain the physical structure of their chromosomes.

Polsky says the detected changes occur in mutant building blocks, in which a cytidine molecule in the on-off switch for the TERT gene is replaced by another building block, called thymidine. Either mutation, C228T or C250T, results in the switch being stuck in the “on” position, helping tumor cells to multiply.

According to Polsky, the blood tests may have advantages over current methods for monitoring the disease because the tests avoid the radiation exposure that comes with CT scans, and the tests can be performed more easily and more often.

The Bio-Rad tests, once clinically validated, are also likely to gain widespread use quickly, he says, because his previous research had shown that similar blood tests for BRAF and NRAS mutations worked better in identifying new tumor growth than existing blood tests for the protein lactate dehydrogenase. Lactate dehydrogenase levels may spike during aggressive tumor growth, but can also rise as a result of other diseases and biological functions.

As part of the ongoing study, researchers checked results from the new tests against 10 tumor samples taken from NYU Langone patients diagnosed with and without metastatic melanoma. They also tested four blood plasma samples (the liquid portion of blood) — from NYU Langone patients with and without the disease. Blood test results matched correctly in all cases known to be either positive or negative for metastatic melanoma. Successful detection occurred, they say, for samples with as little as 1 percent of mutated ctDNA in a typical blood plasma sample of 5 milliliters. Meanwhile, TERT mutations were absent in tests of normal blood plasma and tonsil tissue.

Polsky says further study of the new blood tests are planned to gauge their use in monitoring progression of the aggressive cancer, and to more quickly determine when switching to an alternative therapy is warranted, as well as whether the tests can used to detect other types of cancer, such as brain tumors, that also have TERT mutations.

Funding support for the study was provided by National Cancer Institute grant R21 CA198495, with in-kind support from Bio-Rad, which provided chemical supplies.

Besides Polsky, other NYU Langone/Perlmutter researchers involved in the study were lead study investigators Broderick Corless, BS; and Gregory Chang, MBA; and study co-investigators Mahrukh Sayeda, MS; and Iman Osman, MD. Additional research support was provided by study co-investigators Samantha Cooper, PhD; and George Karlin-Neumann, PhD, at Bio-Rad Laboratories.

Media Inquiries: David March212-404-3528david.march@nyumc.org

Newswise — ORLANDO—

Mothers who binge drink before they become pregnant may be more likely to have children with high blood sugar and other changes in glucose function that increase their risk of developing diabetes as adults, according to a new study conducted in rats. The results will be presented Sunday at the Endocrine Society’s 99th annual meeting in Orlando, Fla.

“The effects of alcohol use during pregnancy on an unborn child are well known, including possible birth defects and learning and behavior problems. However, it is not known whether a mother’s alcohol use before conception also could have negative effects on her child’s health and disease susceptibility during adulthood,” said principal investigator Dipak Sarkar, Ph.D., DPhil, a distinguished professor at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., and director of its endocrine research program.

Binge drinking is common in the United States. Among alcohol users 18 to 44 years old, 15 percent of nonpregnant women and 1.4 percent of pregnant women report that they binge drank in the past month, according to a 2012 phone survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For women, binge drinking is the equivalent of four or more drinks in about two hours.

To assess the effects of preconception alcohol use, Sarkar, with doctoral candidate Ali Al-Yasari, MS, and their colleagues, conducted a study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, in rats, whose basic processes of glucose function are similar to those in humans, Sarkar said. For four weeks, they gave female rats a diet containing 6.7 percent alcohol, which raised their blood alcohol levels to those of binge drinking in humans. Alcohol was then removed from the rats’ diet, and they were bred 3 weeks later, equal to several months in humans. Adult offspring of these rats were compared with control offspring: the offspring of rats that did not receive alcohol before conception. (One control group received regular rat chow and water, and the other received a nonalcoholic liquid diet equal in calories to the alcohol feedings.)

After the rats’ offspring reached adulthood, the researchers used standard laboratory techniques to monitor their levels of blood glucose and insulin and two other important hormones, glucagon and leptin. Glucagon stimulates the liver to convert glycogen (stored glucose) into glucose to move to the blood, making blood glucose levels higher. Although the main function of leptin is inhibiting appetite, it also reduces the glucose-stimulated insulin production by the pancreas.

The research team found that, compared with both groups of control offspring, the offspring of rats exposed to alcohol before conception had several signs of abnormal glucose homeostasis (function). Altered glucose homeostasis reportedly included increased blood glucose levels, decreased insulin levels in the blood and pancreatic tissue, reduced glucagon levels in the blood while being increased in pancreatic tissue, and raised blood levels of leptin.

Additionally, the researchers said they found evidence that preconception alcohol exposure increased the expression of some inflammatory markers in pancreatic tissue. Al-Yasari said this might lower insulin production and action on the liver that increases blood glucose levels. The overexpression of inflammatory markers may be how pre-pregnancy alcohol use altered normal glucose homeostasis in the offspring, he stated.

“These findings suggest that [the effects of] a mother’s alcohol misuse before conception may be passed on to her offspring,” Al-Yasari said. “These changes could have lifelong effects on the offspring’s glucose homeostasis and possibly increase their susceptibility to diabetes.”# # #

Newswise — (NEW YORK —)

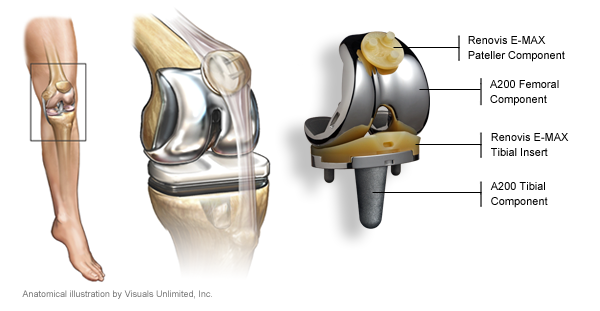

Knee replacement surgery for patients with osteoarthritis, as currently used, provides minimal improvements in quality of life and is economically unattractive, according to a study led by Mount Sinai researchers and published today in the BMJ. However, if the procedure was only offered to patients with more severe symptoms, its effectiveness would rise, and its use would become economically more attractive as well, the researchers said.

“Given its limited effectiveness in individuals with less severely affected physical function, performance of total knee replacement in these patients seems to be economically unjustifiable,” said Bart Ferket, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Population Health Science and Policy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and lead author on the study. “Considerable cost savings could be made by limiting eligibility to patients with more symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Our findings emphasize the need for more research comparing total knee replacement with less expensive, more conservative interventions, particularly in patients with less severe symptoms.”

About 12 percent of adults in the United States are affected by osteoarthritis of the knee. The annual rate of total knee replacement has doubled since 2000, mainly due to expanding eligibility to patients with less severe physical symptoms. The number of procedures performed each year now exceeds 640,000 at a total annual cost of about $10.2 billion, yet health benefits are higher in those with more severe symptoms before surgery.A team of researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, set out to evaluate the impact of total knee replacement on quality of life in people with knee osteoarthritis. They also wanted to estimate differences in lifetime costs and quality adjusted life years or QALYs (a measure of years lived and health during these years) according to level of symptoms.They analyzed data from two U.S. cohort studies: one with 4,498 participants aged 45-79 with or at high risk for knee osteoarthritis from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), and the other involving 2,907 patients from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST). OAI participants were followed up for nine years and MOST patients were followed up for two years. Quality of life was measured using a recognized score of physical and mental function, known as SF-12, and using some osteoarthritis-specific quality of life scores.They found that quality of life outcomes generally improved after knee replacement surgery, although the effect was small. The improvements in quality of life outcomes were found higher when patients with lower physical scores before surgery were operated on.

In a cost-effectiveness analysis, current practice was more expensive and in some cases seemed even less effective compared with scenarios in which total knee replacement was performed only in patients with lower physical function.

“Our findings show opportunity for optimizing delivery of total knee replacement in a cost-effective way, finding the patients who will benefit the most, delivering the treatment at the correct point in their disease progression, and optimizing the cost so we can deliver the benefit to all who need it,” said Madhu Mazumdar, PhD, Director of the Institute for Healthcare Delivery Science at the Mount Sinai Health System, Professor of Biostatistics, Department of Population Health Science and Policy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and co-author of the study.

Funding for the cohort studies used in the analysis was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. Dr. Ferket is supported by the American Heart Association. The researchers have no competing interests to disclose.

About the Mount Sinai Health SystemThe Mount Sinai Health System is an integrated health system committed to providing distinguished care, conducting transformative research, and advancing biomedical education. Structured around seven hospital campuses and a single medical school, the Health System has an extensive ambulatory network and a range of inpatient and outpatient services—from community-based facilities to tertiary and quaternary care.

The System includes approximately 7,100 primary and specialty care physicians; 12 joint-venture ambulatory surgery centers; more than 140 ambulatory practices throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, Long Island, and Florida; and 31 affiliated community health centers. Physicians are affiliated with the renowned Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is ranked among the highest in the nation in National Institutes of Health funding per investigator. The Mount Sinai Hospital is in the “Honor Roll” of best hospitals in America, ranked No. 15 nationally in the 2016-2017 “Best Hospitals” issue of U.S. News & World Report. The Mount Sinai Hospital is also ranked as one of the nation’s top 20 hospitals in Geriatrics, Gastroenterology/GI Surgery, Cardiology/Heart Surgery, Diabetes/Endocrinology, Nephrology, Neurology/Neurosurgery, and Ear, Nose & Throat, and is in the top 50 in four other specialties. New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai is ranked No. 10 nationally for Ophthalmology, while Mount Sinai Beth Israel, Mount Sinai St. Luke's, and Mount Sinai West are ranked regionally. Mount Sinai’s Kravis Children’s Hospital is ranked in seven out of ten pediatric specialties by U.S. News & World Report in "Best Children's Hospitals."

For more information, visit http://www.mountsinai.org/, or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

# # #

Newswise — CLEVELAND—

Bill Kochevar grabbed a mug of water, drew it to his lips and drank through the straw.

His motions were slow and deliberate, but then Kochevar hadn’t moved his right arm or hand for eight years.

And it took some practice to reach and grasp just by thinking about it.

Kochevar, who was paralyzed below his shoulders in a bicycling accident, is believed to be the first person with quadriplegia in the world to have arm and hand movements restored with the help of two temporarily implanted technologies.

A brain-computer interface with recording electrodes under his skull, and a functional electrical stimulation (FES) system* activating his arm and hand, reconnect his brain to paralyzed muscles.

Holding a makeshift handle pierced through a dry sponge, Kochevar scratched the side of his nose with the sponge. He scooped forkfuls of mashed potatoes from a bowl—perhaps his top goal—and savored each mouthful.

“For somebody who’s been injured eight years and couldn’t move, being able to move just that little bit is awesome to me,” said Kochevar, 56, of Cleveland. “It’s better than I thought it would be.”

A video of Kochevar can be found at: https://youtu.be/OHsFkqSM7-AKochevar is the focal point of research led by Case Western Reserve University, the Cleveland Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) Center at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UH). A study of the work will be published in the The Lancet March 28 at 6:30 p.m. U.S. Eastern time.

“He’s really breaking ground for the spinal cord injury community,” said Bob Kirsch, chair of Case Western Reserve’s Department of Biomedical Engineering, executive director of the FES Center and principal investigator (PI) and senior author of the research. “This is a major step toward restoring some independence.”

When asked, people with quadriplegia say their first priority is to scratch an itch, feed themselves or perform other simple functions with their arm and hand, instead of relying on caregivers.

“By taking the brain signals generated when Bill attempts to move, and using them to control the stimulation of his arm and hand, he was able to perform personal functions that were important to him,” said Bolu Ajiboye, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and lead study author.

Technology and training

The research with Kochevar is part of the ongoing BrainGate2* pilot clinical trial being conducted by a consortium of academic and VA institutions assessing the safety and feasibility of the implanted brain-computer interface (BCI) system in people with paralysis. Other investigational BrainGate research has shown that people with paralysis can control a cursor on a computer screen or a robotic arm (www.braingate.org).

“Every day, most of us take for granted that when we will to move, we can move any part of our body with precision and control in multiple directions and those with traumatic spinal cord injury or any other form of paralysis cannot,” said Benjamin Walter, associate professor of Neurology at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Clinical PI of the Cleveland BrainGate2 trial and medical director of the Deep Brain Stimulation Program at UH Cleveland Medical Center.

“The ultimate hope of any of these individuals is to restore this function,” Walter said. “By restoring the communication of the will to move from the brain directly to the body this work will hopefully begin to restore the hope of millions of paralyzed individuals that someday they will be able to move freely again.”

Jonathan Miller, assistant professor of neurosurgery at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and director of the Functional and Restorative Neurosurgery Center at UH, led a team of surgeons who implanted two 96-channel electrode arrays—each about the size of a baby aspirin—in Kochevar’s motor cortex, on the surface of the brain.

The arrays record brain signals created when Kochevar imagines movement of his own arm and hand. The brain-computer interface extracts information from the brain signals about what movements he intends to make, then passes the information to command the electrical stimulation system.

To prepare him to use his arm again, Kochevar first learned how to use his brain signals to move a virtual-reality arm on a computer screen.

“He was able to do it within a few minutes,” Kirsch said. “The code was still in his brain.”

As Kochevar’s ability to move the virtual arm improved through four months of training, the researchers believed he would be capable of controlling his own arm and hand.

Miller then led a team that implanted the FES systems’ 36 electrodes that animate muscles in the upper and lower arm.

The BCI decodes the recorded brain signals into the intended movement command, which is then converted by the FES system into patterns of electrical pulses.

The pulses sent through the FES electrodes trigger the muscles controlling Kochevar’s hand, wrist, arm, elbow and shoulder. To overcome gravity that would otherwise prevent him from raising his arm and reaching, Kochevar uses a mobile arm support, which is also under his brain’s control.

New CapabilitiesEight years of muscle atrophy required rehabilitation. The researchers exercised Kochevar’s arm and hand with cyclical electrical stimulation patterns. Over 45 weeks, his strength, range of motion and endurance improved. As he practiced movements, the researchers adjusted stimulation patterns to further his abilities.

Kochevar can make each joint in his right arm move individually. Or, just by thinking about a task such as feeding himself or getting a drink, the muscles are activated in a coordinated fashion.

When asked to describe how he commanded the arm movements, Kochevar told investigators, “I’m making it move without having to really concentrate hard at it…I just think ‘out’…and it goes.”

Kocehvar is fitted with temporarily implanted FES technology that has a track record of reliable use in people. The BCI and FES system together represent early feasibility that gives the research team insights into the potential future benefit of the combined system.Advances needed to make the combined technology usable outside of a lab are not far from reality, the researchers say. Work is underway to make the brain implant wireless, and the investigators are improving decoding and stimulation patterns needed to make movements more precise. Fully implantable FES systems have already been developed and are also being tested in separate clinical research.

Kochevar welcomes new technology—even if it requires more surgery—that will enable him to move better. “This won’t replace caregivers,” he said. “But, in the long term, people will be able, in a limited way, to do more for themselves.”

The investigational BrainGate technology was initially developed in the Brown University laboratory of John Donoghue, now the founding director of the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland. The implanted recording electrodes are known as the Utah array, originally designed by Richard Normann, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Bioengineering at the University of Utah.

The report in today’s Lancet is the result of a long-running collaboration between Kirsch, Ajiboye and the multi-institutional BrainGate consortium. Leigh Hochberg, MD, PhD, a neurologist and neuroengineer at Massachusetts General Hospital, Brown University and the VA RR&D Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology in Providence, Rhode Island, directs the pilot clinical trial of the BrainGate system and is a study co-author.

“It’s been so inspiring to watch Mr. Kochevar move his own arm and hand just by thinking about it,” Hochberg said. “As an extraordinary participant in this research, he’s teaching us how to design a new generation of neurotechnologies that we all hope will one day restore mobility and independence for people with paralysis.”

Other researchers involved with the study include: Francis R. Willett, Daniel Young, William Memberg, Brian Murphy, PhD, and P. Hunter Peckham, PhD, from Case Western Reserve; Jennifer Sweet, MD, from UH; Harry Hoyen, MD,and Michael Keith, MD, from MetroHealth Medical Center and CWRU School of Medicine; and John Simeral, PhD from Brown University and Providence VA Medical Center.

*CAUTION: Investigational Device. Limited by Federal Law to Investigational Use.

Media contacts:

Bill Lubinger, Case Western Reserve University: 216-368-4443; william.lubinger@case.eduGeorge Stamatis, University Hospitals: 216-346-9323; george.stamatis@uhhosppitals.org

Mary Buckett, Cleveland FES Center: 216-231-3257 or 440-667-5367;mbuckett@FEScenter.org

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY