News

Newswise — BOSTON —

An epidemiological analysis of data from more than 6,000 American and Canadian women with breast cancer finds that post-diagnosis consumption of foods containing isoflavones—estrogen-like compounds primarily found in soy food—is associated with a 21 percent decrease in all-cause mortality. This decrease was seen only in women with hormone-receptor-negative tumors, and in women who were not treated with endocrine therapy such as tamoxifen.

The study, led by nutrition and cancer epidemiologist Fang Fang Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., from the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, was published March 6 in Cancer.

“At the population level, we see an association between isoflavone consumption and reduced risk of death in certain groups of women with breast cancer. Our results suggest, in specific circumstances, there may be a potential benefit to eating more soy foods as part of an overall healthy diet and lifestyle,” said Zhang, who is also the 2016-2017 Miriam E. Nelson Tisch Faculty Fellow at the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life and an adjunct scientist in nutritional epidemiology at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts.

“Since we only examined naturally occurring dietary isoflavone, we do not know the effect of isoflavone from supplements. We recommend that readers keep in mind that soy foods can potentially have an impact, but only as a component of an overall healthy diet,” she adds.

Isoflavones have been shown to slow the growth of breast cancer cells in laboratory studies, and epidemiological analyses in East Asian women with breast cancer found links between higher isoflavone intake and reduced mortality. However, other research has suggested that the estrogen-like effects of isoflavones may reduce the effectiveness of endocrine therapies used to treat breast cancer. Because of this double effect, it remains unknown whether isoflavone consumption should be encouraged or avoided by breast cancer patients.

In the current study, Zhang and her colleagues, including Esther John, Ph.D., senior cancer epidemiologist at the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, analyzed data on 6,235 American and Canadian breast cancer patients from the Breast Cancer Family Registry, a National Cancer Institute-funded program that has collected clinical and questionnaire data on enrolled participants and their families since 1995. Women were sorted into four quartile groups based on the amount of isoflavone they were estimated to have consumed, calculated from self-reported food frequency questionnaires. Mortality was examined after a median follow-up of 9.4 years.

The team found a 21 percent decrease in all-cause mortality among women in the highest quartile of intake, when compared to those in the lowest quartile. The association between isoflavone intake and reduced mortality was strongest in women with tumors that lacked estrogen and progesterone receptors. Women who did not receive endocrine therapy as a treatment for their breast cancer had a weaker, but still significant association. No associations were found for women with hormone-receptor-positive tumors and for women who received endocrine therapy.

While the study categorized women in the highest quartile as those who consumed 1.5 milligrams or more of isoflavone per day—equivalent to a few dried soybeans—the authors caution that individuals tend to underestimate their food intake when filling out questionnaires.

“The comparisons between high and low consumption in our study are valid, but our findings should not be interpreted as a prescription,” Zhang said. “However, based on our results, we do not see a detrimental effect of soy intake among women who were treated with endocrine therapy, which has been hypothesized to be a concern. Especially for women with hormone-receptor-negative breast cancer, soy food products may potentially have a beneficial effect and increase survival.”

The large size and diverse racial/ethnic makeup of the Breast Cancer Family Registry allowed the researchers to evaluate mortality risk across different subtypes of breast cancer and subgroups of patients, and adjust for confounding factors. However, the authors note that dietary isoflavone intake was correlated with socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, which may also play a role in lowering mortality. In particular, women who consumed higher levels of dietary isoflavone were more likely to be Asian Americans, young, physically active, more educated, not overweight, never smokers, and drink no alcohol. Although the team controlled for these factors in the analyses, the possibility of a partial confounding effect on the associations identified in the study cannot be ruled out.

“Whether lifestyle factors can improve survival after diagnosis is an important question for women diagnosed with hormone-receptor negative breast cancer, a more aggressive type of breast cancer. Our findings suggest that survival may be better in patients with a higher consumption of isoflavones from soy food,” John said.

Additional authors on this study are Danielle E. Haslam, nutritional epidemiology doctoral candidate at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, Mary Beth Terry, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology at Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, Julia A. Knight, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto and senior investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Sinai Health System in Toronto, Irene L. Andrulis, Ph.D., professor of molecular genetics at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto and senior investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Sinai Health System in Toronto, Mary Daly, M.D., Ph.D., chair and professor in the department of clinical genetics and director of risk assessment program at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Saundra S. Buys, M.D., medical director of Huntsman Cancer Institute's high risk breast cancer clinic and a professor in the department of medicine at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

This work was supported by an award from National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (CA164920).

Zhang, F. F., Haslam, D. E., Terry, M. B., Knight, J.A., Andrulis, I. L., Daly, M., Buys, S.S., and John, E. M. (2017). Dietary isoflavone intake and all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors: the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer. Published online: March 6, 2017. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.30615. URL upon publication: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/cncr.30615

About the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University

The Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University is the only independent school of nutrition in the United States. The school’s eight degree programs – which focus on questions relating to nutrition and chronic diseases, molecular nutrition, agriculture and sustainability, food security, humanitarian assistance, public health nutrition, and food policy and economics – are renowned for the application of scientific research to national and international policy.

###

Newswise — CHAPEL HILL, NC –

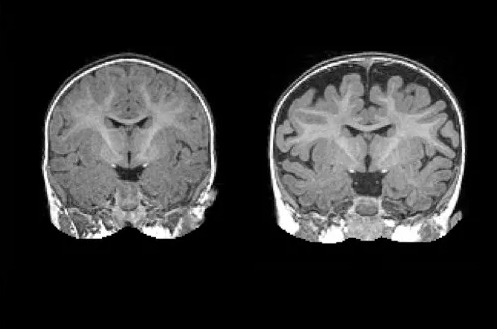

A national research network led by UNC School of Medicine’s Joseph Piven, MD, found that many toddlers diagnosed with autism at two years of age had a substantially greater amount of extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) at six and 12 months of age, before diagnosis is possible. They also found that the more CSF at six months – as measured through MRIs – the more severe the autism symptoms were at two years of age.

“The CSF is easy to see on standard MRIs and points to a potential biomarker of autism before symptoms appear years later,” said Piven, co-senior author of the study, the Thomas E. Castelloe Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry, and director of the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities (CIDD). “We also think this finding provides a potential therapeutic target for a subset of people with autism.”

The findings, published in Biological Psychiatry, point to faulty CSF flow as one of the possible causes of autism for a large subset of people.

“We know that CSF is very important for brain health, and our data suggest that in this large subset of kids, the fluid is not flowing properly,” said Mark Shen, PhD, CIDD postdoctoral fellow and first author of the study. “We don’t expect there’s a single mechanism that explains the cause of the condition for every child. But we think improper CSF flow could be one important mechanism.”

Until the last decade, the scientific and medical communities viewed CSF as merely a protective layer of fluid between the brain and skull, not necessarily important for proper brain development and behavioral health. But scientists then discovered that CSF acted as a crucial filtration system for byproducts of brain metabolism.

Every day, brain cells communicate with each other. These communications cause brain cells to continuously secrete byproducts, such as inflammatory proteins that must be filtered out several times a day. The CSF handles this, and then it is replenished with fresh CSF four times a day in babies and adults.

In 2013, Shen co-led a study of CSF in infants at UC Davis, where he worked with David Amaral, PhD, co-senior author of the current Biological Psychiatry study. Using MRIs, they found substantially greater volumes of CSF in babies that went on to develop autism. But they cautioned the study was small – it included 55 babies, 10 of whom developed autism later – and so it needed to be replicated in a larger study of infants.

When he came to UNC, Shen teamed up with Piven and colleagues of the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS), a network of autism clinical assessment sites at UNC, the University of Pennsylvania, Washington University in St. Louis, and the University of Washington.

In this most recent study of CSF, the researchers enrolled 343 infants, 221 of which were at high risk of developing autism due to having an older sibling with the condition. Forty-seven of these infants were diagnosed with autism at 24 months, and their infant brain MRIs were compared to MRIs of other infants who were not diagnosed with autism at 24 months of age.

The six-month olds who went on to develop autism had 18 percent more CSF than six-month olds who did not develop autism. The amount of CSF remained elevated at 12 and 24 months. Infants who developed the most severe autism symptoms had an even greater amount of CSF – 24 percent greater at six months.

Also, the greater amounts of CSF at six months were associated with poorer gross motor skills, such as head and limb control.

“Normally, autism is diagnosed when the child is two or three years old and beginning to show behavioral symptoms; there are currently no early biological markers,” said David G. Amaral, director of research at the UC Davis MIND Institute. “That there’s an alteration in the distribution of cerebrospinal fluid that we can see on MRIs as early as six months, is a major finding.”

The researchers found that increased CSF predicted with nearly 70 percent accuracy which babies would later be diagnosed with autism. It is not a perfect predictor of autism, but the CSF differences are observable on a standard MRI. “In the future, this sort of CSF imaging could be another tool to help pediatricians detect risks for autism as early as possible,” Shen said.

Piven added, “We can’t yet say for certain that improper CSF flow causes autism. But extra-axial CSF is an early marker, a sign that CSF is not filtering and draining as it should. This is important because improper CSF flow may have downstream effects on the developing brain; it could play a role in the emergence of autism symptoms.”

The National Institutes of Health, Autism Speaks, and the Simons Foundation funded this research.Other researchers included Sun Hyung Kim, Hongbin Gu, Heather C. Hazlett, Robert W. Emerson, Meghan R. Swanson, and Martin A. Styner at the University of North Carolina; Christine W. Nordahl at UC Davis; Robert C. McKinstry and Kelly N. Botteron at Washington University; Dennis Shaw, Stephen R. Dager, and Annette M. Estes at the University of Washington; Jed T. Elison at the University of Minnesota; Vladimir S. Fonov and Alan C. Evans at McGill University; Guido Gerig at New York University; Sarah Paterson at Temple University; Robert T. Schultz at the University of Pennsylvania; and Lonnie Zwaigenbaum at the University of Alberta.

Newswise —

Since the early seventies, scientists have been developing brain-machine interfaces; the main application being the use of neural prosthesis in paralyzed patients or amputees. A prosthetic limb directly controlled by brain activity can partially recover the lost motor function. This is achieved by decoding neuronal activity recorded with electrodes and translating it into robotic movements. Such systems however have limited precision due to the absence of sensory feedback from the artificial limb. Neuroscientists at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, asked whether it was possible to transmit this missing sensation back to the brain by stimulating neural activity in the cortex. They discovered that not only was it possible to create an artificial sensation of neuroprosthetic movements, but that the underlying learning process occurs very rapidly. These findings, published in the scientific journal Neuron, were obtained by resorting to modern imaging and optical stimulation tools, offering an innovative alternative to the classical electrode approach.

Motor function is at the heart of all behavior and allows us to interact with the world. Therefore, replacing a lost limb with a robotic prosthesis is the subject of much research, yet successful outcomes are rare. Why is that? Until this moment, brain-machine interfaces are operated by relying largely on visual perception: the robotic arm is controlled by looking at it. The direct flow of information between the brain and the machine remains thus unidirectional. However, movement perception is not only based on vision but mostly on proprioception, the sensation of where the limb is located in space. “We have therefore asked whether it was possible to establish a bidirectional communication in a brain-machine interface: to simultaneously read out neural activity, translate it into prosthetic movement and reinject sensory feedback of this movement back in the brain”, explains Daniel Huber, professor in the Department of Basic Neurosciences of the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE.Providing artificial sensations of prosthetic movements

In contrast to invasive approaches using electrodes, Daniel Huber’s team specializes in optical techniques for imaging and stimulating brain activity. Using a method called two-photon microscopy, they routinely measure the activity of hundreds of neurons with single cell resolution. “We wanted to test whether mice could learn to control a neural prosthesis by relying uniquely on an artificial sensory feedback signal”, explains Mario Prsa, researcher at UNIGE and the first author of the study. “We imaged neural activity in the motor cortex. When the mouse activated a specific neuron, the one chosen for neuroprosthetic control, we simultaneously applied stimulation proportional to this activity to the sensory cortex using blue light”. Indeed, neurons of the sensory cortex were rendered photosensitive to this light, allowing them to be activated by a series of optical flashes and thus integrate the artificial sensory feedback signal. The mouse was rewarded upon every above-threshold activation, and 20 minutes later, once the association learned, the rodent was able to more frequently generate the correct neuronal activity.

This means that the artificial sensation was not only perceived, but that it was successfully integrated as a feedback of the prosthetic movement. In this manner, the brain-machine interface functions bidirectionally. The Geneva researchers think that the reason why this fabricated sensation is so rapidly assimilated is because it most likely taps into very basic brain functions. Feeling the position of our limbs occurs automatically, without much thought and probably reflects fundamental neural circuit mechanisms. This type of bidirectional interface might allow in the future more precisely displacing robotic arms, feeling touched objects or perceiving the necessary force to grasp them.

At present, the neuroscientists at UNIGE are examining how to produce a more efficient sensory feedback. They are currently capable of doing it for a single movement, but is it also possible to provide multiple feedback channels in parallel? This research sets the groundwork for developing a new generation of more precise, bidirectional neural prostheses.

Towards better understanding the neural mechanisms of neuroprosthetic control

By resorting to modern imaging tools, hundreds of neurons in the surrounding area could also be observed as the mouse learned the neuroprosthetic task. “We know that millions of neural connections exist. However, we discovered that the animal activated only the one neuron chosen for controlling the prosthetic action, and did not recruit any of the neighbouring neurons”, adds Daniel Huber. “This is a very interesting finding since it reveals that the brain can home in on and specifically control the activity of just one single neuron”. Researchers can potentially exploit this knowledge to not only develop more stable and precise decoding techniques, but also gain a better understanding of most basic neural circuit functions. It remains to be discovered what mechanisms are involved in routing signals to the uniquely activated neuron.

Newswise —

Patients treated at mobile health clinics report a high level of engagement in their care and the motivation to pursue healthy behaviors, according to the results of a qualitative study led by Zoe Bouchelle, Harvard Medical School Class of 2017, and communications scholar Heather Carmack of James Madison University.

The findings of the analysis suggest mobile clinics are a powerful tool to engage patients in care and to encourage more active participation in their own treatment, the researchers said. The study, which involved in-depth interviews with 25 patients, ages 19 to 72 treated at Family Van mobile clinic, was published online Feb. 14 in Communication Quarterly.

Mobile health clinics bring free health care services to underserved communities whose residents may lack the means and transportation to visit a regular clinic or a hospital.

“Mobile health clinics are emerging as vital players in the process of rebalancing our health system towards those who have a harder time accessing care,” said study senior author Nancy Oriol, faculty associate dean for community engagement in medical education at HMS. “Such clinics seek to shift the power imbalances and prioritize marginalized voices by listening to patients’ needs and involving them more actively in their own care.”

The Family Van provides a range of services, including blood pressure, blood glucose and cholesterol screenings, vision exams, HIV and STI testing, low-cost dental care and counseling, and referrals. It has served more than 100,000 people since its inception 25 years ago.

The following dominant themes emerged from participant interviews:

• Promoting generosity and inclusion: Participants viewed the Family Van as a vehicle for social justice by helping those in need; providing a safe, welcoming space; and creating a sense of inclusion. Such a view, the researchers point out, underscores the power of mobile health clinics to provide an environment that fosters relationships with patients, which can be difficult to achieve in traditional clinical settings.

• Activating an interest in health by sheer presence: Participants reported that the mere presence of the van and the convenience of being able to simply walk in and get tested stimulated their interest in their own health. Patients reported that they were stimulated to seek care due to the fact that services were provided for free, citing co-pays as a major deterrent to seeking care in a standard setting.

• Fostering motivation for behavior change: Patients also reported feeling empowered to take an active role in their health as a result of health-related education provided by the mobile clinic staff. In addition to administering tests and screenings, the staff provides recommendations and counseling for long-term care and follow-up.

Additionally, many patients reported a desire to encourage family members and friends to be more proactive about their care.

Past research has shown that mobile health clinics can help improve blood pressure outcomes among return patients screened, potentially averting dangerous and costly complications. Chronically elevated blood pressure, or hypertension, is a leading cause of stroke, heart disease and kidney damage.

More than 2,000 mobile health clinics in the United States provide basic screening and health services, including chronic disease management, prenatal care and pediatric care. There are some 6.5 million visits a year to mobile clinics across the U.S. Researchers estimate that on average, mobile health clinics prevent 600 visits to emergency rooms each year.

For more information on the impact of mobile health clinics, visit: http://www.mobilehealthmap.org/impact-report

Newswise — ANN ARBOR, Mich. -

For patients affected by lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis and others, cures for their diseases are incredibly rare, if not nonexistent.

“We really have no option, but to offer them a lung transplantation,” says Vibha Lama, M.D., a professor of internal medicine and associate chief of basic and translational research at Michigan Medicine’s Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine.

“Survival of lung transplantation is worse than all other solid organ transplants,” she says. “The five-year survival rate is only 50 percent, and the 10-year survival rate is as low as 20 percent. For me to tell my patient that this second chance at life comes with this critical limitation is incredibly hard.”

Lama explains that in many lung transplant patients, the body will chronically reject the new lung.

“Small airways of the transplanted lung, or graft, begin scarring and slowly become completely scarred and close up. This process is called bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS),” she says. “The patient will begin to have shortness of breath again, like they did before the transplant, and this scarring can lead to graft problems and ultimately death in some patients. Right now we have nothing to prevent or stop this scarring process once it begins.”

Lama is the senior author on a new paper, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, which examined the scarring process in transplanted lungs in hopes of identifying novel therapies to stop scarring before it starts.

Analyzing cells and their environment

“This study is unique because it actually started from our patients,” Lama says. “Samples were collected from lung transplant patients by going into the lung with a small scope that helps us to insert a liquid into the lung and draw it back, allowing us to study the internal environment of the transplanted organ. This procedure, called bronchoalveolar lavage, is routinely done to rule out acute rejection or infection.”

In 2007, in a study published in JCI, Lama’s team demonstrated that they could isolate novel mesenchymal stem cells from this bronchoalveolar lavage.

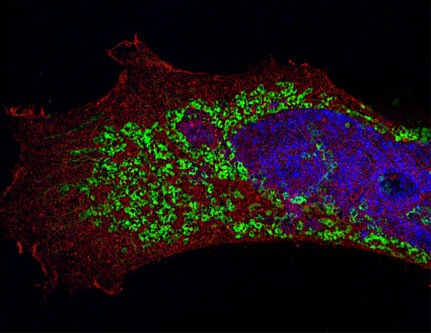

In this new study, Lama and team focused on cells harvested from lung transplant patients who had BOS and those who did not.

“We started investigating cells in patients who have BOS and found that even after being removed from the fibrotic graft, these cells stayed activated, making more collagen, which explained their ability to promote relentless scarring,” Lama says.

As the team dug into what keeps these cells activated, they discovered a chain of upstream signals starting with autotaxin, an enzyme which acts on the cell membrane to generate lysophosphatidic acid. This potent lipid mediator was signaling the cells to produce more collagen, as well as indirectly increased autotaxin levels.

“We found that these cells could regulate themselves by increased autotaxin production, which was being further enhanced by an autocrine loop,” Lama says. “What’s so fascinating about this is that it means the cell no longer needs an inflammatory environment, or stimulation in its environment, to produce the collagen. That’s extremely novel because we have never thought of these cells as essentially cancer cell-like in nature, but they are regulating their own behavior like a cancer cell does.”

She adds, “The dysregulated behavior of these cells essentially makes them become autonomous in behavior and helps us further understand why we can’t stop the scarring process just by changing the environment around the cell, which does not make a difference. They have already begun not listening to anything around them.”

Lama explains that this finding led the team to investigate new therapies.

“If we interrupt this pathway, we could potentially stop further development of lung scarring and save the graft,” she says.

Therapeutic treatments

Building on these findings, Lama and team examined two new therapeutic treatments for their potential in interrupting the pathway.

One treatment, PF-8380, targeted the enzyme, while the other treatment, AM095, targeted the receptor for lysophosphatidic acid.

Using a novel mouse lung transplant model of chronic rejection their laboratory developed, they were able to test if the drugs would decrease the scarring process.

Lama and team found that the mouse models treated with these orally administered drugs were protected from the scarring process of chronic rejection with significantly less fibrosis noted in their transplanted lungs.

The team hopes that these findings will lay the foundation for future clinical trials.

“Drugs targeting this pathway, such as autotaxin inhibitors and LPA1 receptor antagonists, have already been developed and are in clinical trials for other fibrotic conditions of the lung, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” Lama explains. “Now we hope that we can consider similar therapies in BOS, a disease where we have no therapeutic options.”

Lama also explains that these findings should encourage the transplant community in general to consider anti-fibrotic treatments in patients with chronically rejected lungs, instead of just immune suppressive drugs that were given in the past.

“These findings suggest that understanding the pathways that activate a mesenchymal cell and targeting them is crucial if we want to contain the progression of BOS,” Lama says. “We hope this work, which started from the bedside when we examined the lavage fluid from our lung transplant recipients, will be able to be translated back from the bench to the bedside to make an impact on the lives of our patients.”

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — PHILADELPHIA –

Since the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, which provided access to health insurance to millions of previously uninsured adults in the United States, the availability of appointments with primary care physicians has improved for patients with Medicaid and remains unchanged for patients with private coverage, according to new research led by the Perelman School of Medicine and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. The study, which compared new patient appointment availability in 10 states between 2012/13 (before the Affordable Care Act came into effect) and 2016, is published today in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The study found appointment availability for Medicaid enrollees jumped from 57.9 percent to 63.2 percent between 2012/2013 and 2016. “Results of our study should ease concerns that the Affordable Care Act would aggravate access to primary care,” said lead author Daniel Polsky, PhD, a professor of Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine and Health Care Management in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and the executive director of Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. “The finding that more doctors are accepting patients with Medicaid, not fewer, is particularly timely given the active health care reform debate as offers evidence contradicting that the stated criticism of Medicaid that ‘more and more doctors just won’t take Medicaid.”

The study included two waves of data collection, from November 2012 to April 2013 and from February to June 2016. Simulated patients differing in age, sex, race, and ethnicity were randomized to an insurance type (Medicaid or private coverage) and clinical scenario (hypertension or check-up). Participants called in-network primary care practices in Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas, then requested the earliest available appointment with a randomly selected primary care provider. Researchers compared results of the two time periods to determine changes in appointment availability. They also estimated changes in the probability of short wait times (seven days or less) and long wait times (more than 30 days).

In addition to an increase in appointment availability, patients with Medicaid and private coverage experienced somewhat longer wait times. Medicaid callers faced a 6.7 percentage point decrease in short wait times and, among privately insured callers, the share of short wait times decreased 4.1 percentage points and the share of long wait times increased 3.3 percentage points. The authors say the absorption of new patients may explain the increase in wait times, which was similarly observed in Massachusetts after it expanded Medicaid in 2006.

Some initiatives to strengthen primary care delivery, such as raising Medicaid reimbursement rates to Medicare levels for some primary care providers in 2013 and 2014, increasing funds for federally qualified health centers, and expanding the penetration of Medicaid managed care, may explain the findings. Additionally, the authors suggest changes beyond Affordable Care Act initiatives, including team-based clinics, retail clinics, and data sharing, may have expanded capacity in some practices.

Since this study focused solely on new patient appointment requests at in-network offices, further research is needed to determine how health system changes have affected established patients. Additionally, though the 10 states were selected specifically for their diversity along a number of dimensions, the results may not be generalizable to other settings.

Additional authors on the study include Molly Candon from Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, Brendan Saloner from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Katherine Hempstead from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Douglas Wissoker and Genevieve M. Kenney from the Urban Institute, and Karin Rhodes from the Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine. The study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

###

Newswise — La Jolla, Calif., February 27, 2016 (embargoed until 11:00 A.M. EST) — Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) have identified a new regulator of the innate immune response—the immediate, natural immune response to foreign invaders. The study, published recently in Nature Microbiology, suggests that therapeutics that modulate the regulator—an immune checkpoint—may represent the next generation of antiviral drugs, vaccine adjuvants, cancer immunotherapies, and treatments for autoimmune disease.

“We discovered that a protein called K-homology splicing regulatory protein (KHSRP) weakens the immune response to viral RNA,” says Sumit Chanda, Ph.D., director of the Immunity and Pathogenesis Program at SBP, and senior author of the study. “Depleting KHSRP improved immune signaling and reduced viral replication in cell culture and in vivo, suggesting that drugs inhibiting the protein may have therapeutic value.”

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against pathogens—a one-size-fits-all attack on viruses, bacteria, and pretty much anything that looks like an invader. But innate immunity must be carefully regulated. If the response is too slow or too weak, infections can run rampant, and if the trigger is too sensitive or the response is too strong, excessive inflammation or autoimmune diseases can arise.

“That’s where KHSRP comes in,” explains Chanda. “It physically interacts with a protein called retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) to apply the brakes to the innate immune response.”

RIG-I receptors initiate antiviral immunity by detecting viral RNA in the cytoplasm of cells. When they bind viral RNA, they turn on signaling that leads to the production of interferon, a strong inflammatory signal that helps kill viruses, as well as the induction of other antiviral responses. RIG-I receptors also coordinate signaling with other immune factors to modulate the adaptive immune response—the acquired, specialized response that develops after the innate response and provides long-term immunity.

“We identified KHSRP by systematically testing every human proteins to identify those that impact RIG-I signaling,” says Stephen Soonthornvacharin, a recent Ph.D. graduate from the Chanda lab. “We found about 240 proteins, but we focused on KHSRP because it was the only one of the 240 that was found to inhibit the very early steps of RIG-I signaling.”

“Molecules that block KHSRP’s actions could serve as adjuvants—components that heighten the immune response—to vaccines against influenza or hepatitis C, as antiviral drugs, or even next-generation cancer immunotherapies,” Soonthornvacharin adds. “Also, among the 240 RIG-I regulators we identified, 125 appear to activate RIG-I, so finding drugs that inhibit these proteins may be a way to treat autoimmune conditions involving too much interferon, like type 1 diabetes or lupus. Figuring out which ones are promising requires further investigation.”

“We think KHSRP protects against autoimmunity,” adds Chanda. “RIG-I normally recognizes RNA molecules that arise during viral infections, but it can also mistakenly sense RNA present in normal cells. Without KHSRP, the innate immune response could be erroneously turned on when there’s no virus. Increasing the activity of KHSRP might therefore be a way to treat autoimmunity.”“Next, we plan to figure out more of the details of how KHSRP regulates RIG-I,” says Sunnie Yoh, Ph.D., staff scientist in the Chanda lab and a key contributor to the research. “That’s the information that will move us in the direction of developing therapies.”

This research was performed in collaboration with scientists at the Novartis Research Foundation, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Oregon State University Corvallis, the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, and the University of California San Francisco. Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health and the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

# # # #

Newswise — NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. -

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJUH) is the first hospital in New Jersey to offer the Leksell Gamma Knife Icon, the most precise stereotactic radiosurgery system (SRS) currently available to patients diagnosed with primary and secondary brain tumors, vascular disorders, refractory pain, and movement disorders.

Treatments using the new Icon System are available at the hospital's New Brunswick campus and can now be planned and guided by a frameless approach, when appropriate. The frameless mask solution is one of several new features of Icon and is integrated with a high-definition motion management system.

“Increasing the precision of cranial stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is essential for effectively targeting tumor tissue while protecting healthy brain tissue from damage,” said Shabbar Danish, MD, FAANS, Chief of Neurosurgery for Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey; Director of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery Director at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and Director of the Gamma Knife Center at RWJUH. “The new Gamma Knife Icon System now provides the most accurate motion tracking during treatment. Additionally with Gamma Knife, there is a two-to-four fold improvement in sparing normal brain tissue compared to other linear accelerator technologies.”

Nearly 78,000 new cases of primary brain tumors (including cancerous and non-cancerous tumors) were diagnosed in 2015, and today nearly 700,000 people in the U.S. alone are living with primary brain and CNS tumors including malignant tumors, benign tumors, functional disorders (such as essential tremor and severe facial pain (trigeminal neuralgia) vascular disorders and ocular disorders.

Primary and metastatic brain tumors are challenging to treat. While surgery is an effective option, great care must be taken to minimize damage to normal surrounding brain tissue, and patients are at risk for surgical complications such as infection, post-surgical bleeding, and complications due to anesthesia. Traditional radiation therapy delivered to the brain may cause damage to healthy tissue within the brain and other parts of the body, leading to side effects such as hair loss, skin problems, neurocognitive decline and fatigue. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is a non-invasive treatment that focuses multiple beams of radiation to specific areas within the brain, destroying diseased tissue with precision while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissue. The procedure typically involves a single, outpatient session of radiation.

“As a major academic medical center, we are proud to make the latest generation of this technology available to our patients,” explains Kimyatta Washington, MHSA, Assistant Vice President of Oncology Services for RWJUH. “Adoption of this latest advance in SRS technology is consistent with our mission to offer our patients the highest level of care for neurological disorders. Adding Gamma Knife Icon to our multi-disciplinary approach to treating brain cancer and complex neurological disorders in partnership with Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and our other highly advanced cancer treatment centers within RWJBarnabas Health System, will allow us to offer the benefits of cranial SRS to a broader population of patients with brain disease, and to provide these patients with the most precise targeting technology available.”

About Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJUH) is a 965-bed academic medical center with campuses in New Brunswick and Somerville, NJ. Its Centers of Excellence include cardiovascular care from minimally invasive heart surgery to transplantation, cancer care, stroke care, neuroscience, joint replacement, and women’s and children’s care including The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children’s Hospital at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (www.bmsch.org).

As the flagship Cancer Hospital of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and the principal teaching hospital of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, RWJUH is an innovative leader in advancing state-of-the-art care. A Level 1 Trauma Center and the first Pediatric Trauma Center in the state, RWJUH’s New Brunswick campus serves as a national resource in its ground-breaking approaches to emergency preparedness.

RWJUH has been ranked among the best hospitals in America by U.S. News & World Report seven times and has been selected by the publication as a high performing hospital in numerous specialties. The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children’s Hospital has been ranked among the best hospitals in America by U.S. News & World Report three times. In addition, RWJUH was named among the best places to work in health care by Modern Healthcare magazine and received the Equity Care of Award as Top Hospital for Healthcare Diversity and Inclusion from the American Hospital Association.

Both the New Brunswick and Somerset campuses have earned significant national recognition for clinical quality and patient safety, including the prestigious Magnet® Award for Nursing Excellence and “Most Wired” designation by Hospitals and Health Networks Magazine. The Joint Commission and the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services have designated the New Brunswick Campus as a Comprehensive Stroke Center and the Somerset Campus as a Primary Stroke Center.

The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer has rated RWJUH New Brunswick among the nation’s best comprehensive cancer centers and designated the Steeplechase Cancer Center at RWJ Somerset as a Comprehensive Community Cancer Center. The Joint Surgery Center at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Somerset has earned the Joint Commission’s Gold Seal of Approval for total knee and total hip replacement surgery.

Newswise —

Two drugs used to treat asthma and allergies may offer a way to prevent a form of pneumonia that can kill up to 40 percent of people who contract it, researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine have found.

Influenza pneumonia results when a flu infection spreads to alveolar air sacs deep within the lungs. Normally, a flu infection does not progress that far into the lower respiratory tract, but when it does, the results can be deadly. “If infection is severe enough, and the immune response is potent enough, you get injury to these cells and are no longer able to get sufficient oxygen exchange,” explained UVA researcher Thomas J. Braciale, MD, PhD. “As a result of the infection of the cells, you can develop lethal pneumonia and die.”

But early administration of the two asthma drugs, Accolate and Singulair, could prevent the infection of the alveolar cells deep in the lower respiratory tract, Braciale’s research suggests. “The excitement of this is the possibility of someone coming to see the physician with influenza that looks a little more severe than usual and treating them with the drugs Singulair or Accolate and preventing them from getting severe pneumonia,” he said. “The fatality rate from influenza pneumonia can be pretty high, even with all modern techniques to support these patients. Up to 40 percent. So it’s a very serious problem when it occurs.”

Ounce of prevention

Unlike bacterial pneumonia, influenza pneumonia is caused by a virus. That makes it very difficult to treat – and makes the possibility of prevention all the more tantalizing.

“When we look at pandemic strains of influenza that have high mortality rates, one of the best adaptations of those pandemic viruses is their ability to infect these alveolar epithelial cells,” explained researcher Amber Cardani, PhD. “It’s one of the hallmarks for certain strains that cause the lethality in these pandemics.”

Once influenza spreads deep into the lungs, the body’s own immune response can prove harmful, resulting in severe damage to the alveolar air sacs. “It’s an important observation the field is coming to,” Cardani said. “We really need to limit the infection of these lower respiratory airways.”

Stopping the flu virus

The researchers determined that the alveolar epithelial cells are typically protected from influenza infection by immune cells called alveolar macrophages. In some instances, however, the flu virus can prevent the macrophages from carrying out their protective function, allowing the epithelial cells to become vulnerable to infection. “It’s not as though they lack alveolar macrophages, it’s just that their alveolar macrophages don’t work right when they get exposed to the flu,” Braciale said. “And those are the types of patients, who potentially would eventually go to the intensive care unit, that we think could be treated early in infection with Accolate or Singulair to prevent infection of these epithelial cells and prevent lethal infection.”

For their next steps, the researchers are consulting with colleagues to determine if patients being treated with Accolate and Singulair are less likely to develop influenza pneumonia during flu outbreaks.

“This was a totally unexpected observation,” Braciale said. “When I told multiple colleagues who are infectious disease or pulmonary physicians, they were absolutely flabbergasted.”

Findings published

The findings have been published online by the scientific journal PLOS Pathogens. It was written by Cardani, Adam Boulton, Taeg S. Kim and Braciale.

Braciale and Cardani are both part of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology and UVA’s Beirne B. Carter Center for Immunology Research. Braciale’s primary appointment is with the Department of Pathology.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant R01AI015608-35, and the NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grants T32 GM007055 and T32 GM007055.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — Research Triangle Park, NC—

Pot brownies may be a thing of the past as there are new edible marijuana products, or edibles, on the market, including chocolates, candies, and cookies. These products are legally sold in Colorado and Washington, and according to a new study conducted by RTI International, changes to their labels are needed to ensure people know what they are consuming and that they are safely consuming the products.

The new study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, found that many of the adults who participated in the study are not reading labels, and if they are, information is often hard to decipher.

“We discovered that people think there is too much information listed on the labels of edibles, thus potentially overlooking important information on consumption advice” said Sheryl C. Cates, corresponding author of the study and senior research policy analyst at RTI. “Our study also determined that labels often do not make it clear that the product contains marijuana, which can lead to accidental ingestion.”

Researchers conducted four focus groups in Denver and Seattle with 94 adult consumers and nonconsumers. Participants revealed concerns with edible labels, and suggested that more needs to be done to inform and educate consumers and nonconsumers about the possible risks of edibles.

In 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first two states in the United States to legalize marijuana for recreational use with retail sales starting in 2014. According to the Colorado Department of Revenue, edibles accounted for nearly half of total marijuana sales in the state for 2014. In Washington, edibles accounted for about 40 percent of marijuana sales according to Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (reported in 2016).

“As the popularity of edibles grow, it is important that labels clearly and concisely provide consumers important information,” Cates said. “Web- and video-based education and using graphics on labels may be easy, cost-effective ways to inform buyers and the public.”

Since conducting this research, the states of Colorado and Washington have changed some of the requirements for labeling of edibles based on increasing public concern. Lessons learned from Colorado and Washington, can help inform the labeling of edibles as additional states allow the sale of edibles for recreational use.

To learn about RTI’s marijuana research, visit our Emerging Issues page.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY