News

Newswise — New Brunswick, N.J. –

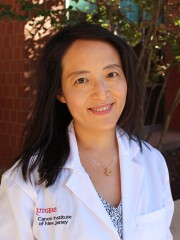

Research from investigators at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and Princeton University has identified a new approach to cancer therapy in cutting off a cancer cell’s ‘fuel supply’ by targeting a cellular survival mechanism known as autophagy. Rutgers Cancer Institute Deputy Director Eileen P. White, PhD, distinguished professor of molecular biology and biochemistry in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and Rutgers Cancer Institute researcher‘Jessie’ Yanxiang Guo, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, are the co-corresponding authors of the work published in the August 10 edition of Genes & Development (doi: 10.1101/gad.283416.116). They share more about the research, which focused on lung cancers driven by the Kras protein:

Q: Why is this topic important to explore?A: Between 85 to 90 percent of lung cancers are non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and response to standard treatment is typically poor. Some subsets of patients with metastatic disease have seen improved survival thanks to recently developed therapies that target particular lung cancer mutations in the EGFR, MAPK, and PI3K signaling pathways. Mutations in the Ras protein family – including Kras – are frequently detected in NSCLC, but drugs directly targeting Ras mutations in NSCLC have not been effective. Understanding the critical cellular process of autophagy and its role in Kras-driven tumor cells may lead to new therapeutic approaches for NSCLC.

Q: What is autophagy and how does this process relate to what we already know? A: Cells eat themselves in times of starvation and stress by a process called autophagy. It was long believed that autophagy allows cells to digest and recycle part of themselves to support their metabolism and survive interruptions in their supply of nutrients. But whether this is true, and what the recycling was needed for, was not known. Cancer cells turn on autophagy and use it to survive too, even more so than normal cells. Previously, the White and Guo groups discovered that cancer cells activated by the Ras protein family require autophagy for cell maintenance, metabolic stress tolerance and tumor development. When Ras proteins are ‘switched on,’ they have the ability to turn on other proteins that can activate genes responsible for cell growth and survival. Therefore, understanding what autophagy does can reveal an inherent weakness exploitable for cancer therapy.

Q: How did your team approach the work and what did you learn?A: The Guo, Chang and White groups at Rutgers worked together with the Rabinowitz group at Princeton University to find out how autophagy enables cancer cells to survive stress. Using the tumor derived cell lines generated from genetically engineered mouse models for Kras-driven NSCLC, we traced the path of intracellular components cannibalized by autophagy through an analytical laboratory technique known as mass spectroscopy. We found that cancer cells do indeed breakdown and recycle themselves to survive starvation. This cannibalization of cellular parts provides fuel to the powerhouses of the cell, the mitochondria, to maintain their energy levels. Thus, blocking autophagy cuts off the fuel supply to the powerhouses, creating and energy crisis and ultimately cancer cell death.

Q: What is the implication of this finding?A: This finding suggests that cutting of ‘fuel’ to cancer cells by blocking autophagy may be a potential therapeutic strategy for Kras-driven lung cancers. Future research should clarify if the autophagy pathways identified in Kras-driven lung cancers can be applied to other forms of cancer.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants: R01 CA130893, R01 CA188096, R01 CA193970, R01 CA163591, K22 CA190521, P30 CA072720; and the Functional Genomics shared resources of Rutgers Cancer Institute for mitochondrial DNA extraction and DNA sequencing.

###

Newswise —

As humans evolved over many thousands of years, our bodies developed a system to help us when we start running and suddenly need more oxygen. Now, using that innate reflex as inspiration, UCLA researchers have developed a noninvasive way to treat potentially harmful breathing problems in babies who were born prematurely.

The technique uses a simple device that tricks babies’ brains into thinking they are running, which prompts them to breathe.

Each year, about 150,000 babies are born after only 23 to 34 weeks of gestation, which puts them at risk for apnea of prematurity, a condition in which breathing stops, often for several seconds, accompanied by severe falls in oxygenation.

The condition occurs because — in infants whose systems not yet fully formed — the respiratory system ignores or cannot use the body’s signals to breathe. Compounding the danger, premature newborns’ lungs are not fully developed, and therefore do not have much oxygen in reserve. When breathing stops in these periods of apnea, the level of oxygen in the body goes down, and the heart rate can drop. That combination can damage the lungs and eyes, injure the nerves to the heart, affect the hormonal system (which can lead to diabetes later in life), or injure the brain (which can result in behavioral problems later in life).

Hospitals use a range of approaches to minimize the duration of premature babies’ breathing pauses — placing them on their stomach, forcing air into the lungs with a facemask and giving caffeine to stimulate the brain — but none is perfect and each carries other risks.

According to Dr. Ronald Harper, a distinguished professor of neurobiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, even newborns have the innate mechanism that triggers increased breathing.

“When our feet hit the ground running, we flex muscles and joints that have nerve fibers leading to the brain which signal that the body is running,” he said. “This message is coupled with another set of fibers to parts of the brain that regulate breathing and sends a signal that those parts need to increase breathing. Fortunately, that coupling exists even in extremely young infants.”

The idea to use an external breathing device to treat apnea of prematurity arose over a cup of coffee between Harper and Dr. Kalpashri Kesavan, a neonatologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA, when the conversation turned to how a baby’s breathing could be supported if the brain was told the baby was running or walking.

Harper’s lab, which focuses on brain mechanisms that drive breathing during sleep, had already developed a device that he had intended to test for treating people with breathing problems. The device is a pager-sized box with wires that connect to small disks which are placed on the skin over the joints of the feet and hands. (Placing them on the hands is another nod to how the human body evolved: Early humans ran on all fours, so nerves in the hands are still involved in signaling the brain that the body is running.) Once the battery-powered machine is turned on, the disks gently vibrate, which triggers nerve fibers to alert the brain that the limb is moving.

“We thought that if this reflex were going to work for any kind of sleep disorder with breathing problems, then premature infants would be the No. 1 target, because breathing stoppages are so common and have the potential to do so much injury,” Kesavan said. “It’s almost like it was naturally made for them.”

The researchers tested the device on 15 premature infants who were born after 23 to 34 weeks of gestation, and who were experiencing breathing pauses and low oxygen. The disks were placed on one hand and one foot, and the device was turned on for six hours at a time, followed by six hours off, for a total of 24 hours.

The scientists compared the babies’ vital signs during the periods when the device was on with the times when it was off. They found that when it was on, the number of incidents when babies’ oxygen levels were low was reduced by 33 percent and the number of breathing pauses was 40 percent lower than when it was off. The device also reduced low–heart-rate episodes by 65 percent, which is especially significant because slow heart rate can impair the flow of blood to vital tissues. The findings were published online in the Journal PLOS One.

The researchers now plan to study the approach on a larger number of patients and over a longer period of time. They’ll also study the effects of the device on blood pressure and other cardio-respiratory measures, as well as its impact on sleep quality. Breathing stoppages typically wake infants, and reducing the number of pauses in their breathing should lead to less disturbed sleep.

While most premature babies eventually grow out of their breathing problems, it can take weeks to months before their respiratory systems develop sufficiently to allow them to breathe on their own at all times.

“Long-term use of the device could decrease breathing pauses, maintain normal oxygen levels, stabilize the cardiovascular system and help improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants,” Kesavan said. “We may be able to bring about this change with something that is noninvasive, drug-free and has no side effects, and there is nothing better than that.”

Harper is also testing the device on adolescents who suffer breathing problems due to spinal cord injuries and adults with sleep-disordered breathing, including obstructive sleep apnea.

The University of California has applied for a patent for the device, and is discussing its commercialization with several companies.

The study’s other authors are Paul Frank, Daniella Cordero and Dr. Peyman Benharash, all of UCLA, and the research was supported by grants from the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute.

Justin Stephens/Mattel Children's Hospital UCLA

A Simple Treatment for Common Breathing Problem of Premature Infants | UCLA Health Newsroom

Newswise — MADISON, Wis. —

Imbed Biosciences today received clearance from the Food and Drug Administration to market its patented wound dressing for human use. The dressing it calls Microlyte Ag is a sheet as thin as Saran Wrap and can conform to the bumps and crevices of a wound, says company CEO Ankit Agarwal.

The dressing is now cleared by the FDA as a class II medical device, for prescription and over-the-counter use.

Like many dressings now used to treat burns and other persistent wounds, Microlyte Ag contains silver to kill bacteria – but in much smaller quantities."Silver is an excellent antimicrobial agent," says Agarwal, a co-founder of the company in the Madison suburb of Fitchburg, "as it is active against a broad range of bacteria and yeast. But the large silver loads found in conventional silver dressings can be toxic to skin cells. Our dressing uses as little as 1 percent as much silver as the competition, and yet the tests we submitted to the FDA showed that Microlyte kills more than 99.99 percent of bacteria that it contacts."

That kill ratio even appeared in tests against some of the nastiest hospital-acquired superbugs, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.

Microlyte overcomes a key problem with existing dressings: stiffness. Under a low-power microscope, a wound has bumps and fissures — hiding places for bacteria. The Microlyte dressing inherently adheres to moist surfaces and is so flexible that it drops into the fissures, leading to the sweet combination of greater destruction of bacteria at much lower doses of silver.Microlyte has several other advantages, Agarwal says. It retains moisture yet is ultrathin and breathable, allowing oxygen to reach the wound and gases to exit, all factors that promote healing. The slow release of the silver means the dressing can remain in place for at least one day. And because the material is a hydrogel (a water-based gel), it can simply be rinsed off as needed before replacement.

Experience with animals shows that the ultra-thin dressing simply sloughs off as the wound heals. All of these advantages should reduce the need to change dressings, which can be so painful that sedation is needed, especially for children.

“Reducing or eliminating dressing changes reduces the pain that the patient experiences,” says co-founder Michael Schurr, chair of general surgery at the Mountain Area Health Education Center in Asheville, North Carolina, and adjunct professor of surgery at the University of North Carolina. “It also reduces costs in supplies and reduces the burden to the health care system that supplies visiting nurses to do the dressing changes.”

"We are seeing in a limited number of cases that it does provide us with a remarkable new tool for dealing with chronic wounds" in dogs and cats treated at the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, says Jonathan McAnulty, chair of the Department of Surgical Sciences. "We certainly have no reason to think that this will be different with humans,” adds McAnulty, who is also a company co-founder. “The principles are the same, and a lot of the problems are the same."

The dramatic closure of wounds that have resisted months of conventional treatment "suggests that chronic bacterial contamination of the wound surface, even when it looks relatively healthy, is a significant factor inhibiting healing in many cases," McAnulty says. "Once we treat with our dressing, we start to see very dramatic closure of these wounds."

McAnulty says he’s starting to use Microlyte earlier in treatment. "Certainly it seems appropriate for prevention of infection as well as treatment."The ultra-thin dressing material was invented in the lab of Nicholas Abbott, a UW–Madison professor of chemical and biological engineering, when Agarwal was a postdoctoral fellow and where he is now an honorary associate scientist. The dressing will compete in the $2 billion market sector of "advanced wound dressings," which are used to treat diabetic ulcers, venous ulcers, burns, bedsores and other difficult wounds.

Imbed has 10 employees. The company is developing other ideas for wound treatment and discussing commercial-scale production of Microlyte. Currently, it plans to reach the market through licensing agreements with hospital suppliers.

# # #

Newswise — Boston, MA--

In a retrospective study analyzing patients' medical records, researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital found that patients' race significantly affected their longevity by increasing the likelihood of death after receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). ADT was used to reduce the size of the prostate to make a patient eligible for prostate brachytherapy. These findings are published in the August 4, 2016 issue of Cancer.

Konstantin Kovtun, MD, a resident at BWH, Anthony D'Amico, MD, PhD, chief of Genitourinary Radiation Oncology at BWH, and colleagues, analyzed the medical records of over 7000 men from the Chicago Prostate Cancer Center who had low or favorable-intermediate risk prostate cancer, 20 percent of whom were treated with ADT in order to reduce the size of their prostate gland to make them eligible for brachytherapy. They found that African-American men who were treated with ADT had a 77 percent higher risk of death when compared to non-African American men, the causes of which were not due to prostate cancer.

"When African-American men were exposed to an average of only four months of hormone therapy, primarily used to make the prostate small enough for brachytherapy, they suffered from higher mortality rates due to causes other than prostate cancer than non-African American men," Kovtun explained. "This leads us to believe that there may be something intrinsic to the biology of African-American men that predisposes them to this increased risk of death and that this deserves further study."

ADT is an antihormone treatment that lowers a man's testosterone level, and been used to reduce the size of the prostate and in turn make the subsequent brachytherapy treatment possible. This team of BWH researchers is the first to observe the negative effects of ADT in the context of racial differences, specifically comparing African-American men to non-African American men after adjusting for age, comorbidities such as heart disease and established prostate cancer prognostic factors.

"These results show that careful consideration should be taken by physicians when recommending treatment for low or favorable-intermediate prostate cancer, a cancer that very few men die of even without treatment," D'Amico said. "There is no evidence that ADT followed by brachytherapy increases the chance of cure in comparison to other treatments, such an external beam radiation therapy alone, in these men with favorable risk prostate cancer. The subsequent risks of ADT, specifically linked to African-American men, deserve further study."

Future research is indicated to explore the basis for the observation of shortened survival in African-American men following ADT use with the hope of developing effect and personalized treatments for all men with prostate cancer.

Investigators report no funding sources for this research.

###

Newswise —

Escherichia coli K1 (E. coli K1) continues to be a major threat to the health of young infants. Affecting the central nervous system, it causes neonatal meningitis by multiplying in immune cells, such as macrophages, and then disseminating into the bloodstream to subsequently invade the blood-brain barrier. Neonatal and childhood meningitis in particular results in long-term neurological problems such as seizures or ADHD in up to half of the survivors.

Meningitis can be caused by bacterial, fungal or viral pathogens. One hallmark of bacterial meningitis is reduced glucose levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients, which allows a physician to quickly begin appropriate antibiotic treatment.

The reason for the reduced glucose levels associated with bacterial meningitis was believed to be the need for glucose as fuel by infiltrating immune cells in response to infection. However, the possibility that the bacteria itself could manipulate glucose concentrations in the brain had not been explored before now.

Scientists at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) report that glucose transporters, which transfer glucose from the blood to the brain, are inhibited by E. coli K1 during meningitis.

“We found that expression of glucose transporters is completely shut down by bacteria, leaving insufficient fuel for the immune cells to fight off the infection,” said the study’s first author, Subramanian Krishnan, PhD, of the Division of Infectious Diseases at CHLA.

Specifically, the study – reported online in The Journal of Infectious Diseases – shows that E. coli K1 modulates the protein peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) and glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) levels at the blood-brain barrier in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. This causes inhibition of glucose uptake and the disruption of the blood-brain barrier integrity.

The suppression of PPAR-γ and GLUT-1 levels in mouse models of bacterial meningitis caused extensive neurological effects. The researchers showed that a two-day treatment regimen with partial or selective PPAR-γ agonists (Telmisartan and Rosiglitazone – both FDA-approved drugs) ameliorated the pathological outcomes of infection in mice by inducing expression of glucose transporters.

“Modulation of PPAR-γ and GLUT-1 levels may boost the immune system to fight infection,” said principal investigator Prasadarao V. Nemani, PhD of CHLA and the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. “Our findings could lead to a novel way of treating children with meningitis and reducing long-term neurological problems.”

Additional contributors to the study include Alexander C. Chang, PhD of CHLA and Professor Brian M. Stoltz of the California Institute of Technology. This work was supported by funds from NIAID (AI40567) and NICHD (NS73115).

Newswise — DALLAS – Relying on readings from smart phone health apps may not be a smart idea.Examining 100 healthy volunteers, Dr. John Alexander, Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology and Pain Management at UT Southwestern Medical Center, compared vital signs readings from four smart phone apps with readings from a standard medical monitor and found worrisome differences.

The four routine measurements taken were heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Researchers found substantive differences in all four types of readings by the apps.

“The lack of correlation suggests that the applications do not provide clinically meaningful data,” Dr. Alexander said.

Particularly concerning was the fact that the gap between app-reading and standard monitor-reading for blood pressures widened as blood pressure numbers increased, suggesting that hypertensive patients who need to monitor their blood pressure more frequently are also the most likely to get inaccurate readings from apps. “It’s not surprising that these apps did not perform as well as standard medical equipment,” Dr. Alexander said. “When you think about it, in a clinical setting you wrap a blood pressure cuff around the arm and you are actually measuring the pressure of the blood flowing through the arm, so you would expect that to be more accurate than touching your finger to a phone.”

The study appeared in the Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing.

Essential oils a poisoning danger for young childrenDALLAS – Essential oils, popular home remedies for everything from digestive ailments to insomnia, increasingly are being accidentally ingested by small children, sending them to emergency care, a new study found.

A study of calls to the Texas Poison Control Center Network found more than 1,200 calls concerning exposure to essential oils during a recent 10-year period, with the incidence continuing to rise, according to Dr. Kurt Kleinschmidt, Professor of Emergency Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health & Hospital Systems. The oils, which are highly concentrated “essence” of the flowers, herbs, and trees they are extracted from, have pleasant aromas that can be alluring to children. “The oils often smell very nice – they may even smell like food – which can lead kids to drink them. But then the taste is bitter so they often choke and aspirate them into their lungs,” Dr. Kleinschmidt says.

Taking these liquids into the lungs can lead to pneumonia.

There are scores of essential oils, and while some may be relatively harmless when swallowed, many can have serious consequences, including agitation, hallucinations, liver damage, and seizures. Even skin exposure can, in some cases, be harmful to children, who have thinner skin than adults and may absorb them more easily into the blood stream.

To be safe, Dr. Kleinschmidt says, treat essential oils as you would medicine. Refrain from using essential oils on children and, most important, store them safely in a place where young children cannot get to them. Phosphates in processed foods may hike blood pressure

DALLAS – A diet high in phosphates, which are often present in large quantities in processed foods and cola drinks, may lead to increases in blood pressure, especially during exercise.Dr. Wanpen Vongpatanasin, a hypertension specialist at UT Southwestern Medical Center, said the typical American diet includes about double the amount of phosphate as recommended. “Inorganic phosphates are added in large quantities to processed foods as preservatives and flavor enhancers,” says Dr. Vongpatanasin, Professor of Internal Medicine. Phosphates occur naturally in many foods, including dairy products, meat, fish, and baking powder, but it is the consumption of fast foods, processed foods, and bottled drinks that can push phosphate levels up, she says. For example, a block of Parmesan cheese contains phosphates, but when Parmesan is sold in a grated or shredded form, additional phosphates may be added to keep it from sticking.

When examining food labels, look for anything that contains “phos,” such as calcium phosphate, disodium phosphate, or monopotassium phosphate. Dr. Vongpatanasin holds the Norman and Audrey Kaplan Chair in Hypertension

Gotta wear shadesDALLAS – Ophthalmologists at UT Southwestern Medical Center remind everyone to protect their eyes from the sun. The surface of the eye and the cornea are particularly vulnerable to the sun’s rays.

“Excessive exposure may increase the risk for the formation of a fleshy tissue over the cornea, some forms of cataract, and possibly macular degeneration,” says Dr. V. Vinod Mootha, a specialist in cornea and external disease, as well as refractive and cataract surgery. “Sunglasses should be used by adults and children when outdoors for prolonged periods of time. For eyeglass wearers, polycarbonate lenses, which are thin and shatterproof, offer protection from ultraviolet radiation.”

UVB exposure is higher on sunny days (especially at noon) and low-ozone days. UT Southwestern is spreading sun safety awareness with sunglass photos on Facebook. To join, snap a selfie wearing your favorite pair of sunglasses and post it with the hashtag #utswshades.

6 Ways to save summer skinDALLAS – As temperatures peak this summer, UT Southwestern cancer specialists remind you to protect your skin.Skin cancer, caused by damaging ultraviolet radiation from the sun, is the most common of all cancers in the U.S. Fortunately, it’s also one of the most preventable forms of the disease.

“Overexposure to ultraviolet radiation is the most preventable risk factor for skin cancer, but skin cancer’s incidence rates continue to rise,” says Dr. Rohit Sharma, a surgeon at UT Southwestern Medical Center who specializes in melanoma and soft-tissue sarcoma.

To be safe in the sun, Dr. Sharma recommends:• Generously apply sunscreen to all exposed skin using a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects against both UVA and UVB rays and has a SPF of at least 30. • Be sure to use enough sunscreen for adequate protection. The skin should be reasonably saturated to assure an adequate amount has been applied—typically a shot glass full for lotions.• Pay attention to the water resistant profile of the individual sunscreen. When exercising or swimming, you will need to observe this time frame for reapplication. At a minimum, reapply every two hours, even on cloudy days. This applies to both lotions and sprays.• Avoid tanning outdoors and tanning beds indoors. Ultraviolet light from tanning beds and the sun causes skin cancer and wrinkling. Use a sunless self-tanning product instead.• Wear protective clothing, including long sleeves, sunglasses, and a hat that shades the face.• Seek shade and remember that the sun’s rays are strongest between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.

About UT Southwestern Medical CenterUT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution’s faculty includes many distinguished members, including six who have been awarded Nobel Prizes since 1985. The faculty of almost 2,800 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide medical care in about 80 specialties to more than 100,000 hospitalized patients and oversee approximately 2.2 million outpatient visits a year.

###

Newswise — LOS ANGELES —

A cardiac imaging study led by Hossein Bahrami, MD, PhD, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC), along with investigators from Johns Hopkins University and five other institutions, showed a correlation between higher inflammatory biomarkers and an increased prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). CAD is a narrowing of the arteries, likely due to the presence of calcified and non-calcified plaque. The findings were published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) on June 27, 2016.

Researchers examined nearly 925 men, 575 of whom were infected with HIV, from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. The researchers used computed tomography (CT) angiography to detect signs of subclinical CAD, such as narrowed arteries and the amount, density and calcification of plaque. Participants were also measured for the presence of seven inflammatory biomarkers. This study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is the largest coronary CT scan imaging study on men infected with HIV to date.

“We found that men infected with HIV had higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers than men who were not infected,” said Bahrami. “There was a strong, independent association between the presence of these inflammatory biomarkers and subclinical CAD detected by CT scan. Although this study does not definitely prove the causal relationship between these markers and heart disease, it is suggestive of a possible role that persistent inflammation (even in HIV infected patients that are under appropriate treatments) may play in increasing the risk of heart disease in these patients.”

HIV-infected individuals are at an estimated twofold higher risk of CAD compared to those who are not infected with HIV. The development of antiretroviral therapy has significantly prolonged the lifespans of those living with HIV infection. However, they are more prone to chronic illness, such as cardiovascular disease and CAD, and they present at a younger age. These factors combined have made research into treating chronic illness in men with HIV all the more important.

The CT imaging was crucial to this study, as researchers were able to detect subclinical CAD in a younger population rather than waiting until participants exhibited clinical symptoms. Moreover, researchers were using a broader set of inflammatory markers than in past studies, which provides more information about inflammatory pathways involved and potential causes for inflammation.

“Inflammation has only recently been studied as a possible reason for chronic heart disease,” said Bahrami. “Confirming the relationship between HIV-related inflammation and the marked increase of CAD among men infected with HIV allows us to move forward in our attempts to better manage the health of these patients according to their specific medical needs.”

In ongoing research efforts at the Keck School, Bahrami and team are also using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study the changes in heart muscle, as well as details of coronary artery function in men affected by HIV. This advanced form of imaging evaluates several features of the heart that could not be evaluated with cardiovascular CT scans. This ongoing project is significant, as HIV-infected patients appear to have even higher risk of abnormalities in the heart muscles compared to their increased risk of coronary artery disease. Bahrami’s research hopes to illuminate what causes HIV-related inflammation, as well as identify specific pathways involved and the best means of treatment or management of heart diseases in HIV patients.

###

Should we be warning consumers about over-consumption of meat as well as sugar?

Newswise —

That's the question being raised by a team of researchers from the University of Adelaide, who say meat in the modern diet offers surplus energy, and is contributing to the prevalence of global obesity.

Comparative anatomy and human evolution experts from the University's School of Medicine have been studying the correlation between meat consumption and obesity rates in 170 countries.

"Our findings are likely to be controversial because they suggest that meat contributes to obesity prevalence worldwide at the same extent as sugar," says Professor Maciej Henneberg, head of the Biological Anthropology and Comparative Anatomy Research Unit.

"In the analysis of obesity prevalence across 170 countries, we have found that sugar availability in a nation explains 50% of obesity variation while meat availability another 50%. After correcting for differences in nations' wealth (Gross Domestic Product), calorie consumption, levels of urbanization and of physical inactivity, which are all major contributors to obesity, sugar availability remained an important factor, contributing independently 13%, while meat contributed another 13% to obesity.

"While we believe it's important that the public should be alert to the over-consumption of sugar and some fats in their diets, based on our findings we believe meat protein in the human diet is also making a significant contribution to obesity," Professor Henneberg says.

The research has been conducted by PhD student Wenpeng You, who recently presented the findings of his work at the 18th International Conference on Nutrition and Food Sciences in Zurich, Switzerland. This research has also formed the basis of two papers on the issue, published in BMC Nutrition and the Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences.

"There is a dogma that fats and carbohydrates, especially fats, are the major factors contributing to obesity," Mr You says.

"Whether we like it or not, fats and carbohydrates in modern diets are supplying enough energy to meet our daily needs. Because meat protein is digested later than fats and carbohydrates, this makes the energy we receive from protein a surplus, which is then converted and stored as fat in the human body."

Mr You says there have been several other academic papers showing that meat consumption is related to obesity, but the authors have often argued that it's the fat content in meat that contributes to the problem. "On the contrary, we believe the protein in meat is directly contributing to obesity," Mr You says.

Professor Henneberg says: "It would be irresponsible to interpret these findings as meaning that it's okay to keep eating a diet high in fats and carbohydrates. Clearly, that is not okay, and this is a serious issue for our modern diet and human health.

"Nevertheless, it is important that we show the contribution meat protein is making to obesity so that we can better understand what is happening. In the modern world in which we live, in order to curb obesity it may make sense for dietary guidelines to advise eating less meat, as well as eating less sugar," he says.

Newswise — PHILADELPHIA –

Today, researchers presented findings at the 68th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting that DNA found circulating in the bloodstream—known as cell-free DNA—can be used to identify liver transplant patients with acute rejection with greater accuracy than conventional liver function tests. This cell-free DNA test could help liver transplant patients receive crucial treatment for rejection faster, and has the potential to improve the prognosis of kidney and heart transplant patients as well.

Episodes of acute rejection—rejection that takes place in the first few months after an organ transplant—are relatively common. In liver transplant patients in particular, acute rejection develops in about 20% of those treated with standard immunosuppressive therapy. Monitoring for the onset of rejection so that healthcare providers can swiftly counteract it is therefore critical for the long-term survival of organ transplant recipients. However, the gold standard for identifying rejection is biopsy, which is expensive and invasive, and at present there are no effective blood tests to take its place.

A team of researchers led by Ekkehard Schütz, MD, PhD, from Chronix Biomedical in Göttingen, Germany set out to determine whether a blood test for graft-derived cell-free DNA—which is cell-free DNA from a transplanted organ—could identify liver transplant patients with acute rejection. In a first-of-its-kind prospective multicenter trial, they monitored graft-derived cell-free DNA in the blood of 106 adult liver transplant recipients for at least one year post transplant. They found that in the 87 stable patients with no signs of graft injury and who were negative for hepatitis C virus infection, the median graft-derived cell-free DNA percentage decreased within the first week to a baseline level of <10% of total cell-free DNA concentrations. However, in the 20 patients with samples drawn during biopsy-proven acute rejection periods, graft-derived cell-free DNA levels were about 10-fold higher than those observed in the stable patients.

Overall, Schütz and colleagues determined that by testing for graft-derived cell-free DNA levels >10%, they were able to identify more than 90% of liver transplant patients with acute rejection—which is a substantially higher percentage than what conventional liver function tests can identify. They also believe that this test could detect heart and kidney transplant rejection, and are conducting additional studies to confirm this.

“This is really a universal test—you can use it for all kinds of solid organ transplantation since it’s just detecting the graft DNA, and it’s independent of what graft you are looking at,” said Schütz. “It will allow us to start treating these patients as early as possible, which not only impacts the acute situation that the patient is suffering at the time, but also impacts the long term survival of the graft. If we are able to diagnose rejection quickly enough—within a day or one and a half days—and the treating physician can react, then we can avoid really high-grade rejections further down the line.”

In addition to this study, researchers will present the latest in cell-free DNA tests at the AACC Annual Scientific Meeting & Clinical Lab Expo, including:

• Research demonstrating that a blood test for genetic mutations in the cell-free DNA of lung cancer patients can be used to inform treatment selection and serve as an alternative to tissue biopsy. “EGFR analysis in cfDNA reflects tumor heterogeneity and has prognostic value in non-small cell lung cancer” (A-013)

• New findings that elevated levels of cell-free DNA in prostate cancer patients could predict which patients have a lower chance of survival and need more aggressive treatment. “Circulating free DNA assessment of prognostic biomarkers in prostate cancer” (A-019)

• A next-generation sequencing test for graft-derived cell-free DNA that can also be used for organ transplant surveillance. “Analytical validation of a clinical-grade next-generation sequencing assay for assessing allograft injury in solid organ transplant recipients” (B-365)

________________________________________

Session InformationAACC Annual Scientific Meeting registration is free for members of the media. Reporters can register online here:https://www.xpressreg.net/register/aacc0716/media/landing.asp

Abstract A-121: Graft-derived cell-free DNA – a promising rejection marker in liver transplantation – results from a prospective multicenter trialwill be presented during Session 32101: Hot Topics in Clinical ChemistryMonday, August 110:30 a.m. – Noon114 Lecture Hall

Scientific Posters A-013 and A-019Tuesday, August 29:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. (presenting authors in attendance from 12:30–1:30 p.m.)Terrace Ballroom

Scientific Poster B-365Wednesday, August 39:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. (presenting author in attendance from 12:30–1:30 p.m.)Terrace Ballroom

All sessions and scientific posters will be presented at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia.

About the 68th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting & Clinical Lab ExpoThe AACC Annual Scientific Meeting offers 5 days packed with opportunities to learn about exciting science from July 31–August 4. Plenary sessions feature the latest research on the use of and testing for cannabis, combating premature death due to preventable causes such as tobacco and alcohol, the development of an “intelligent” surgical knife, programmable bio-nano-chips, and the epigenetic causes of disease.

At the AACC Clinical Lab Expo, more than 750 exhibitors will fill the show floor of Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Convention Center, with displays of the latest diagnostic technology, including but not limited to mobile health, molecular diagnostics, mass spectrometry, point-of-care, and automation.

About AACCDedicated to achieving better health through laboratory medicine, AACC brings together more than 50,000 clinical laboratory professionals, physicians, research scientists, and business leaders from around the world focused on clinical chemistry, molecular diagnostics, mass spectrometry, translational medicine, lab management, and other areas of progressing laboratory science. Since 1948, AACC has worked to advance the common interests of the field, providing programs that advance scientific collaboration, knowledge, expertise, and innovation. For more information, visit www.aacc.org.

Newswise — BINGHAMTON, NY –

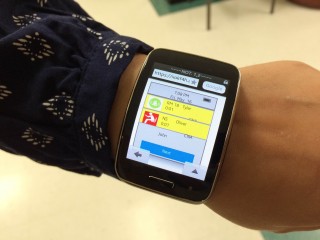

Poor communication systems at nursing homes can lead to serious injury for residents who are not tended to in a timely manner. A new smartwatch app being developed at Binghamton University could help certified nursing assistants (CNAs) respond to alerts more quickly and help prevent falls.

Binghamton University researchers Assistant Professor of Systems Science and Industrial Engineering Huiyang Li and PhD candidate Haneen Ali are developing a smartwatch application to improve communication and notification systems for nursing homes, which are often faulty and inefficient. The proposed design integrates all of the existing safety systems at nursing homes—e.g., call lights, chair and bed alarms, wander guards, calling-for-help functions—and provides alerts to users. Through a process of iterative design and evaluation with prospective users, a final design was well received by nursing experts in geriatric care, and at local nursing homes. An on-going evaluation study shows that using this system reduces staff response time to alarms.

“The problem associated with not responding in time is that residents tend to stand up or go to the bathroom by themselves. If they’re not strong enough, they can’t support the weight. And if they have to wait, they will just get up and go. And that leads to falls,” said Li. “We wanted to design a better system that improves notification and also, potentially, communication in nursing homes. The improvement of notification will potentially help staff to do a better job and, eventually, improve patient safety. Whenever residents need help, they have a way to call for help, and messages will be delivered to staff in an effective way.”

Most nursing homes use a call light system, where residents push a button inside of their room to send an alert, and bed and chair pads with pressure sensors that send an alert when a resident sits or stands up. When nurses are working down the hallway, they might not hear or see these alerts. “With our system, we provide an informative and customized message for different alarms. The message contains the resident’s name, the type of alarm, the room number and the CNA who is responsible. The smartwatch will be on the CNA’s wrist, so it’s accessible all the time. They can see the message, hear the alarm, and feel the vibration, whether they are working down the hallway or inside the rooms,” said Li.

Every CNA who uses the app sees a different display, as it is personalized to the user’s specific task assignment. When CNAs start their shift, they will sign in and add their assigned residents. When a resident triggers an alert, a message will pop up on everyone’s screen indicating who the resident is, their room number, and the type of alert (e.g., an exit from a chair).

“The alert message is more informative than the existing system and, at the same time, it will help nurses to prioritize. We will mark or highight alarms from residents who are actually assigned to whoever is using the app,” said Li.

“The CNAs are exited about this idea and they are interested in this device. They would like to see the adoption of new technologies in their working environment because all of the problems in their current situation,” said Ali.

Li and Ali hope to test the system in the future using a high-fidelity prototype at real nursing homes. While buying a smartwatch for every employee would be an added expense to nursing homes, the researchers believe that the benefits of this app would far outweigh the cost, particularly with the increasing availability of low-cost smartwatches.

“Falls, skin problems—these kind of facility acquired conditions can cost a hospital a lot of money. If the system can actually reduce falls, reduce adverse events, improve patient safety, and also improve quality of care, hospitals will save money.”

The paper, “Designing a Smart Watch Interface for a Notification and Communication System for Nursing Homes,” was presented at the Human-Computer Interaction International Conference 2016.