News

Newswise —

To treat or not to treat? That is the question researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) hope to answer with a new advance that could help doctors and their cancer patients decide if a particular therapy would be worth pursuing.

Berkeley Lab researchers identified 14 genes regulating genome integrity that were consistently overexpressed in a wide variety of cancers. They then created a scoring system based upon the degree of gene overexpression. For several major types of cancer, including breast and lung cancers, the higher the score, the worse the prognosis. Perhaps more importantly, scores could accurately predict patient response to specific cancer treatments.

The researchers said the findings, to be published Aug. 31 in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to a new biomarker for the early stages of tumor development. The information obtained could help reduce the use of cancer treatments that have a low probability of helping.

Overtreating Cancer

“The history of cancer treatment is filled with overreaction," said the study's principal investigator, Gary Karpen, a senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Division of Biological Systems and Engineering with a joint appointment at UC Berkeley’s Department of Molecular and Cell Biology. "It is part of the ethics of cancer treatment to err on the side of overtreatment, but these treatments have serious side effects associated with them. For some people, it may be causing more trouble than if the growth was left untreated."

One of the challenges is that there has been no reliable way to determine at an early stage if patients will respond to chemotherapy and radiation therapy, said study lead author Weiguo Zhang, a project scientist at Berkeley Lab.

"Even for early stage cancer patients, such as lung cancers, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy are routinely used in treatment, but overtreatment is a major challenge," said Zhang. "For certain types of early stage lung cancer patients, there are estimates that adjuvant chemotherapy improves five-year survival only about 10 percent, on average, which is not great considering the collateral damage caused by this treatment.”

The researchers noted that there are many factors a doctor and patient must consider in treatment decisions, but this biomarker could become a valuable tool when deciding whether to use a particular therapy or not.

Study co-author Anshu Jain, an oncologist at the Ashland Bellefonte Cancer Center in Kentucky and a clinical instructor at the Yale School of Medicine, added that the real value of this work may be in helping doctors and patients consider alternatives to the typical course of treatment.

“These findings are very exciting,” said Jain. “The biomarker score provides predictive and prognostic information separate from and independent of clinical and pathologic tumor characteristics that oncologists have available today and which often provide only limited clinical value.”

Hunting for New Biomarkers

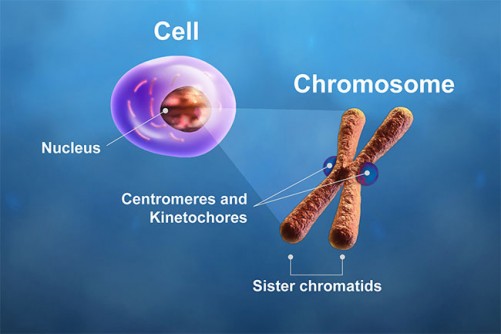

The study authors focused on genes regulating the function of centromeres and kinetochores – the essential sites on chromosomes that spindle fibers attach to during cell division – based upon results from earlier research by the Karpen group and other labs in the field. In normal cell division, microtubule spindles latch on to the kinetochores, pulling the chromosome's two chromatids apart.

What the Karpen team previously found in fruit flies is that the overexpression of a specific centromere protein resulted in extra spindle attachment sites on the chromosomes.

"This essentially makes new centromeres functional at more than one place on the chromosome, and this is a huge problem because the spindle tries to connect to all the sites," said Karpen. "If you have two or more of these sites on the chromosome, the spindles are pulling in too many directions, and you end up breaking the chromosome during cell division. So overexpression of these genes may be a major contributing factor to chromosomal instability, which is a hallmark of all cancers."

This chromosomal instability has long been recognized as a characteristic of cancer, but its cause has remained unclear.

To determine if centromeres play a role in chromosome instability in human cancers, the researchers analyzed many public datasets from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, the Broad Institute and other organizations that together contained thousands of human clinical tumor samples from at least a dozen types of cancers. The researchers screened 31 genes involved in regulating centromere and kinetochore function to find the 14 that were consistently overexpressed in cancer tissue.

The extensive records included information on DNA mutations and chromosome rearrangements, the presence and levels of specific proteins, the stage of tumor growth at the time the patient was diagnosed, treatments given, and patient status in the years following diagnosis and treatment. This allowed the researchers to correlate the centromere and kinetochore gene expression score (CES) with patient outcomes either with or without treatments.

Genome Instability and Cancer Therapy

"We were surprised to find such a strong correlation between CES and things like whether the patient survived five years later," said Karpen. "Another finding – one that is counterintuitive – is that high expression of these centromere genes is also related to more effective chemotherapy and radiation therapy."

The researchers hypothesized that the degree of chromosomal instability may also make cancer cells more vulnerable to the effects of chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

"In other words, there's a threshold of genome instability," said Zhang. "At low to medium-high levels, the cancer thrives. But at much higher levels, the cancer cells are more susceptible to the additional DNA damage caused by the treatment. This is a really key point."

The researchers pointed out that they found no link between very high levels of genome instability and improved patient survival without adjuvant treatments.

Translating these findings into clinical advice and practice will take more research, the study authors caution. They are working to find that threshold of genome instability so that in the future, doctors and patients can make informed decisions about how to move forward.

“Future steps will include investigating the CES in prospective clinical studies for validation in carefully selected patient cohorts," said Jain. "By establishing the clinical significance of the CES, oncologists will have greater confidence in guiding cancer patients toward treatments with the greatest benefit.”

Other co-authors of the study are Jian-Hua Mao at Berkeley Lab’s Division of Biological Systems and Engineering; Wei Zhu at the Cellular Biomedicine Group in Shanghai; and Ke Liu and James Brown at Berkeley Lab's Division of Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology. Mao and Zhu provided critical expertise in bioinformatics for this research.

The National Institutes of Health supported this work.

###

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE –

Starting dialysis treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) should be a shared decision made by an informed patient based on discussions with a physician and family members. However, many older dialysis patients say they feel voiceless in the decision-making process and are unaware of more conservative management approaches that could help them avoid initiating a treatment that reduces their quality of life, according to a study led by Tufts University researchers.

The study, published online in Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation in advance of print, also found that patients who perceived they did not have a choice in starting dialysis reported low satisfaction with the treatment, despite acknowledging its life-extending benefits.

The research coincides with the recent increase of attention to poor end-of-life care in the United States. The study’s link between the process of decision-making and satisfaction with treatment choices affirms the need to prioritize better understanding of shared decision-making in the older patient population.

The findings also highlight how decisions about dialysis initiation are made by members of the growing dialysis population in the United States, which has increased nearly 60 percent between 2000 and 2012, most dramatically among those aged 75 and older, according to the U.S. Renal Data System’s 2014 Annual Data Report. The study also demonstrates that patients who actively engage in decision-making are more satisfied with their outcomes, according to researchers.

“For some patients, dialysis may be the best treatment that aligns with their preferences and goals. But our study found that many of our respondents did not know that starting dialysis was voluntary and that they had a different option,” said Keren Ladin, Ph.D., first author on the paper. Ladin is an assistant professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine. “Patient-centered care requires better communication between patients and providers, including better understanding how potential treatments may affect patients’ goals of care and lifestyle preferences.”

Recent studies show that for elderly ESRD patients, dialysis and conservative management are similarly effective at extending life, although dialysis significantly impacts quality of life. Consequently, the decision to start dialysis for elderly patients should be driven by their priorities and personal goals, said Ladin. The study found that key decision-making factors for patients include: independence, ability to travel, social participation, not burdening loved ones, continuing meaningful activities, and avoiding pain and fatigue.

The qualitative study, which focused on 31 patients in greater Boston age 65 and older with an average age of 78, found multiple barriers to shared decision-making, including:

• A perception among patients that dialysis was necessary to prevent imminent death; • A perception among patients that the decision to begin dialysis was solely up to their physicians;• A lack of communication of important prognostic information for the patient from a doctor; and• A patient’s deference to the views of clinicians and family members who often override a patient’s expressed preferences, fueled by a desire to be a “good patient.”

As a result, most patients who said they felt less engaged in the decision-making process reported feeling dissatisfied with their treatment outcomes. Many focused on unexpected setbacks from dialysis and expressed feelings of distress about the impact of the treatment on their independence and overall energy.

By contrast, the research found that patients reported actively making choices between peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. In this process, most patients reported their choice involved careful research and conversations with clinicians and family members.

Ladin said the research illustrates the value of delivering the highest quality care while respecting patient autonomy.

“While we cannot cure ESRD at this point, we can help patients achieve their goals and live out their last state of life according to their wishes,” said Ladin.

Additional authors of this study are Naomi Lin, a graduate student in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the Research on Aging, Ethics and Community Health (REACH Lab) both at Tufts University; Emily Hanh and Gregory Zhang, both former undergraduate students in the Department of Community Health and research assistants in the REACH Lab, who graduated in 2016; Susan Koch-Weser, Ph.D., of the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine; and Daniel E. Weiner, MD, MS, of the Department of Medicine at Tufts Medical Center.

This study was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number KL2TR001063 and the Neubauer Faculty Fellowship at Tufts University. Dr. Weiner receives indirect salary support for research projects from Dialysis, Inc. paid through Tufts Medical Center.

Keren Ladin, Naomi Lin, Emily Hahn, Gregory Zhang, Susan Koch-Weser, Daniel E. Weiner, “Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions,” Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, published online August 30 in advance of print, DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfw307.

Newswise —

Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine have identified 34 neural factors that predict adolescent alcohol consumption. The list, based upon complex algorithms analyzing data from neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging studies, was significantly more accurate —approximately 74 percent — than demographic information alone.

The findings are published in the current issue of American Journal of Psychiatry.

“Underage alcohol consumption is a significant problem in this country,” said senior author Susan F. Tapert, PhD, professor of psychiatry. “Being able to identify at-risk children before they begin drinking heavily has immense clinical and public health implications. Our findings provide evidence that it’s possible to predict which adolescents are most likely to begin drinking heavily by age 18.”

Underage drinking is common in the United States, with approximately two-thirds of 18-year-olds reporting alcohol use. Though illegal, the Centers for Disease Control says drinkers between the ages of 12 and 21 account for 11 percent of all alcohol consumed in the United States.

The adverse consequences of adolescent drinking are well-documented: higher rates of violence, missing school, drunk driving, driving with a drunk driver, suicide and risky sexual behavior. Alcohol consumption accounts for more than 5,000 adolescent deaths each year in the U.S.

Individual consequences are no less onerous, with adolescent drinking contributing to memory, learning and behavioral problems, changes in brain development with long-lasting effects and greater likelihood for abuse of other drugs.

A mix of social, psychological and biological mechanisms are believed to contribute to alcohol use during adolescence. Demographic risk factors include being male, having higher levels of psychological problems and associating positive outcomes with alcohol (i.e. drinking is fun).

The authors note that past neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies have suggested it might be possible to quantify the underlying behavioral mechanisms of risk for substance abuse. These include poorer performance on tests of executive functioning, comparatively less brain activation of working memory, inhibition and reward processing and less brain volume in regions associated with impulsivity, reward sensitivity and decision making.

In the American Journal of Psychiatry study, 137 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 14 who were “substance-naïve” (97 percent had never tried alcohol) underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests and functional magnetic resonance imaging of their brains. They were then assessed annually. By age 18, just over half of the youths (70) were moderate to heavy users of alcohol (based on drinking frequency and quantity); the remaining 67 study participants continued to be nonusers.

The scientists employed a machine learning algorithm known as “random forests” to develop a predictive model. Random forest classification is capable of accommodating large sets of variables while using smaller study samples to produce consistently robust predictions.

Among the findings, 12- to 14-year-olds were more likely to begin drinking by age 18 if:

They were male and/or came from a higher socioeconomic background

They reported dating, possessed more externalized behaviors, such as lying or cheating, and believed alcohol would benefit them in social settings

They performed poorly on executive function tests

Their neuroimaging results indicated thinner cortices – the outer layer of neural tissue covering the brain

The authors said neuroimaging significantly increased predictive accuracy, both in terms of clarifying implicated brain morphology and noting the activation of 20 diffusely distributed brain regions involved in alcohol initiation.

The study did not extend to the question of early marijuana use because only 15 percent of the sample reported eventually using marijuana more than 30 times, but the authors said it was possible that the reported risk factors for alcohol use also apply to marijuana and other illicit substances. They said further and larger studies are necessary.

“The value of this particular study is that it provides a documented path for other researchers to follow, to replicate and expand upon our findings,” said Tapert. “Ultimately, of course, the goal is to have a final, validated model that physicians and others can use to predict adolescent alcohol use and prevent it.”

Co-authors include: Lindsay M. Squeglia, Medical University of South Carolina; Tali M. Bali, Stanford University; Joanna Jacobus, Ty Brumback, and Scott F. Sorg , UC San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System; Benjamin S. McKenna, and Tam T. Nguyen-Louie, UC San Diego; and Martin P. Paulus, Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Tulsa, OK.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA13149, U01 AA021692, T32 AA013525, R01 DA016663, P20 DA027843) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01 DA041089, K12 DA031794, T32 DA031098).

###

Newswise — Westminster, Colo. —

The popular Paleo diet is based on eating foods thought to be available to our ancestors during the Paleolithic era, before the advent of dairy or processed grains. Findings from a small study suggest that people who followed the Paleo diet for only eight weeks experienced positive effects on heart health. Preliminary findings from this research will be presented at the American Physiological Society’s Inflammation, Immunity and Cardiovascular Disease conference.

“Very few studies have examined the Paleo diet in seemingly healthy participants, despite the prevalence of this dietary practice in health and fitness enthusiasts,” said study author Chad Dolan, a graduate student researcher at University of Houston Laboratory of Integrative Physiology.

The researchers asked eight healthy people who normally consumed a traditional Western diet high in processed foods to switch to the Paleo diet—which consists of minimally processed foods—for eight weeks. The participants received a sample Paleo diet menu and recipe guide, as well as initial counseling on how to incorporate the Paleo diet into their everyday lives. They were told to eat as much food as they wanted while following the diet.

The researchers found that the study participants experienced a 35 percent increase in levels of interlukin-10 (IL-10), a signaling molecule secreted by immune cells. A low IL-10 value can predict increased heart attack risk in people who also have high levels of inflammation. Scientist think that high IL-10 levels may counteract inflammation, providing a protective effect for blood vessels.

Although the researchers have not yet analyzed inflammation levels in the study participants, the increase in IL-10 could suggest a lower risk for cardiovascular disease after following the Paleo diet. The researchers also observed changes in other biomarkers of inflammation, but further investigation is needed to understand whether these changes indicate increased inflammation or a protective mechanism at work.

Even though the study was not designed to promote weight loss, the participants did drop some pounds during the eight-week trial. Compared with what they regularly ate before the study, participants reported consuming around 22 percent fewer calories and 44 percent fewer grams of carbohydrates on the Paleo diet.

This preliminary feasibility study did not include a control group of people not following the diet, making it difficult to determine if the changes observed in inflammation biomarkers resulted from specific food choices, reduced calories, fewer carbohydrates or weight loss.

“This study’s findings add to the possibility that short-term dietary changes from a traditional Western pattern of eating to foods promoted in the Paleo diet may improve health—or, at the very least, the diet does not have negative health implications in terms of the parameters we studied,” Dolan said. “If our research continues to show that the Paleo diet produces detectable changes in healthy individuals, it will substantiate claims made by those supporting this diet for the past few decades and provide preliminary evidence for another therapeutic strategy for cardiovascular disease and coronary artery disease prevention.”

The researchers caution that the current findings are both preliminary and incomplete in this group of participants. They plan to conduct a study with a greater number of people who follow the diet for a longer period of time to analyze how it affects various risk factors for cardiovascular and coronary artery disease, cellular immune function and metabolic health.

The study was a collaborative effort between the Human Performance Laboratory at Chatham University in Pittsburgh and the University of Houston Laboratory of Integrative Physiology.

Dolan will present “Effects of an 8-week Paleo dietary intervention on inflammatory cytokines” at a poster session on Friday, Aug. 26, from 12:45 to 2:45 p.m. in the Westminster IV room of the Westin Westminster Hotel.

Newswise —

Researchers know that youth with a family history of alcoholism have a greater risk of developing an alcohol use disorder; this heightened vulnerability may be due to impulsive behavior. For this study, researchers examined “waiting” impulsivity – a tendency toward prematurely responding to a reward, and previously associated with a predisposition to drinking. The study sample comprised young, moderate-to-heavy social drinkers who were either positive (FHP) or negative (FHN) for a family history of alcoholism. Impulsivity was assessed after an alcoholic or non-alcoholic drink.

Two groups of young male and female social drinkers (34 women, 30 men; 18-33 years old) were given alcohol (0.8g/kg) or a placebo. The FHP group (n= 24) had first-degree relatives with problems of alcohol misuse; the FHN group (n=40) did not. Participants completed four variants of the Five-Choice Serial Reaction Time task, which measures waiting impulsivity. Other types of impulsive behavior were also tested, using the Stop Signal Reaction Time, Information Sampling Task, Delay Discounting Questionnaire, Two-Choice Impulsivity Paradigm, and Time Estimation.

The FHP drinkers showed higher waiting impulsivity levels than FHN drinkers when tested for attentional load. However, the FHP group showed less impulsive behavior on the Information Sampling Task. All participants showed alcohol-impaired inhibitory control on the Stop Signal Reaction Time test. In summary, assessing exaggerated waiting impulsivity may help identify those offspring of alcoholics who are at risk for developing alcohol addiction.

Newswise — Westminster, Colo.—

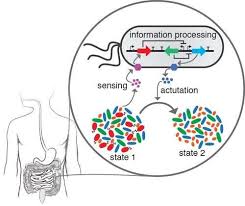

A new therapy that involves engineered gut bacteria may one day help reduce the health problems that come with obesity. Incorporating the engineered bacteria into the guts of mice both kept them from gaining weight and protected them against some of the negative health effects of obesity. Researchers will present their findings today at the American Physiological Society’s Inflammation, Immunity and Cardiovascular Disease conference.

More than one-third of adults in the U.S. are obese, putting them at greater risk for conditions such as fatty liver disease—caused by fatty deposits building up in the liver—and atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of the arteries. Scientists have recently discovered that the microorganisms living in our gut, known as the gut microbiota, play an important role in obesity and may offer a new therapeutic target.

Researchers led by Sean Davies, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology at Vanderbilt University, are studying whether obesity-related diseases might be treated or even prevented by altering the gut microbiota. To find out, they engineered gut bacteria that produce a small lipid that helps suppress appetite and reduce inflammation. People who are obese typically produce less of this lipid, which is made by the small intestine.

“We have previously shown that this approach with engineered bacteria could inhibit obesity when standard mice were fed a high-fat diet,” Davies said. “Our new studies focused on mice highly prone to develop atherosclerosis and fatty liver disease, and we showed that the engineered bacteria were beneficial not only in inhibiting obesity, but also in protecting against fatty liver disease and somewhat against atherosclerosis.”

The researchers found that standard mice fed a high-fat diet while also receiving the engineered bacteria via drinking water gained less body weight and body fat than mice given standard drinking water or control bacteria. They also gave the engineered bacteria to mice with increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis and fatty liver disease. These mice accumulated less fat in the liver and showed reduced expression of markers of liver fibrosis, compared to mice that did not receive the treatment. The treated mice also exhibited a modest trend toward reduced atherosclerotic plaques.

“Some day in the future, it might be possible to treat the worst effects of obesity simply by administering these bacteria,” Davies said. “Because of the sustainability of gut bacteria, this treatment would not need to be every day.”

Davies will present “Altering the microbiota for weight control” at the Inflammation and Hypertension during Pregnancy and Gender Differences symposium on Friday, Aug. 26, from 8:30 to 9 p.m. in the Westminster III room of the Westin Westminster Hotel.

Newswise —

Texas A&M researchers have shown, for the first time, evidence that standing desks in classrooms can slow the increase in elementary school children’s body mass index (BMI)—a key indicator of obesity—by an average of 5.24 percentile points. The research was published today in the American Journal of Public Health.

“Research around the world has shown that standing desks are positive for the teachers in terms of classroom management and student engagement, as well as positive for the children for their health, cognitive functioning and academic achievement,” said Mark Benden, PhD, CPE, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at the Texas A&M School of Public Health and an author of the study. “It’s literally a win-win, and now we have hard data that shows it is beneficial for weight control.”

Twenty-four classrooms at three elementary schools (eight in each of the three schools) in College Station, Texas, participated in the study. At each school, four classrooms were outfitted with stand-biased desks (which allow students to sit on a stool or stand at will) and four classrooms in each school acted as a control and utilized standard classroom desks. The researchers followed the same students—193 in all—from the beginning of third grade to the end of fourth grade.

The researchers found that the students who had the stand-biased desks for both years averaged a three percent drop in BMI while those in traditional desks showed the two percent increase typically associated with getting older. However, even those who spent just one year in classrooms with stand-biased desks had lower mean BMIs than those students in traditional seated classrooms for their third and fourth grade years. In addition, there weren’t major differences between boys and girls, or between students of different races, suggesting that this intervention works across demographic groups.

“Classrooms with stand-biased desks are part of what we call an Activity Permissive Learning Environment (APLE), which means that teachers don’t tell children to ‘sit down,’ or ‘sit still’ during class,” Benden said. “Instead, these types of desks encourage the students to move instead of being forced to sit in poorly fitting, hard plastic chairs for six or seven hours of their day.”

Many school-based initiatives for weight loss focus on better, more nutritious cafeteria lunches, and although these programs are important, they don’t focus on the other side of weight control: calories expended.

Previous studies from Benden’s lab have shown that children who stand burn 15 percent more calories, on average, than those who sit in class, but this is the first study showing, over two years, that BMI decreases over time (versus controls) when using a stand-biased desk.

“It is challenging to just measure weight loss with children,” Benden said, “because children are supposed to be gaining weight as they get older and taller.”

At the beginning of this study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), roughly 79 percent of the students were of normal weight category, 12 percent were overweight and nine percent were obese, according to height and weight measurements made by the researchers. These are better numbers than nationally, where 14.9 percent of children were overweight and 16.9 percent were obese in 2012. The fact that the students who started at a healthy weight benefited from stand-biased desks as much as they did might indicate that these desks help students who aren’t overweight maintain their BMI, while at the same time help those who start out overweight or obese get to a healthier weight.

These desks, designed by Benden and his team, are called stand-biased, not “standing” because they do include a tall stool the students can perch on if they so choose. They also include a footrest, a vital feature because it allows children to get their lower backs out of tension and reduce leg fatigue to stand more comfortably over time. These United States-patented desk designs are now licensed to Stand2Learn, which has commercialized the products through translational research focused on moving university studies to publicly available solutions.

“Sit less, move more,” Benden said. “That’s our message.”

###

Newswise —

Neurons in the brain interact by sending each other chemical messages, so-called neurotransmitters. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter, which is important to restrain neural activity, preventing neurons from getting too trigger-happy and from firing too much or responding to irrelevant stimuli.

Researchers led by Dr Tobias Bast in the School of Psychology at The University of Nottingham have found that faulty inhibitory neurotransmission and abnormally increased activity in the hippocampus impairs our memory and attention.

Their latest research -- "Hippocampal neural disinhibition causes attentional and memory deficits" -- published in the academic journal Cerebral Cortex, has implications for understanding cognitive deficits in a variety of brain disorders, including schizophrenia, age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's, and for the treatment of cognitive deficits.

The hippocampus -- a part of the brain that sits within our temporal lobes -- plays a major role in our everyday memory of events and of where and when they happen -- for example remembering where we parked our car before going shopping.

This research has shown that a lack of restraint in the neural firing within the hippocampus disrupts hippocampus-dependent memory; in addition, such aberrant neuron firing within the hippocampus also disrupted attention -- a cognitive function that does not normally require the hippocampus.

Increased activity can be more detrimental than reduced activity

Dr Bast, said: "Our research carried out in rats highlights the importance of GABAergic inhibition within the hippocampus for memory performance and for attention. The finding that faulty inhibition disrupts memory suggests that memory depends on well-balanced neural activity within the hippocampus, with both too much and too little causing impairments. This is an important finding because traditionally, memory impairments have mainly been associated with reduced activity or lesions of the hippocampus.

"Our second important finding is that faulty inhibition leading to increased neural activity within the hippocampus disrupts attention, a cognitive function that does not normally require the hippocampus, but depends on the prefrontal cortex. This probably reflects that there are very strong neuronal connections between hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Our finding suggests that aberrant hippocampal activity has a knock-on effect on the prefrontal cortex, thereby disrupting attention."

"Overall, our new findings show that increased activity of a brain region, due to faulty inhibitory neurotransmission, can be more detrimental to cognitive function than reduced activity or a lesion. Increased activity within a brain region can disrupt not only the function of the region itself -- in this case hippocampus-dependent memory -- but also the function of other regions to which it is connected -- in this case prefrontal cortex-dependent attention."

Adding to existing research findingsDr Bast's research is motivated by recent clinical findings that patients in early stages of schizophrenia, age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's show faulty inhibition and increased activity within the hippocampus. The new study, where inhibition in the hippocampus of rats was disrupted before the animals took part in tests of attention and memory, revealed that such faulty inhibition and aberrant activity within the hippocampus causes the type of memory and attentional impairments seen in patients.

This research adds to the team's recent findings, where they found that attention was disrupted by faulty inhibition and increased activity within the prefrontal cortex, a brain region important for attention.

Dr Bast, said: "Overall, these findings highlight that higher brain functions, such as attention and memory, depend on well-balanced neural activity within the underlying brain regions."

Potential target for new treatments

This research has important implications for treating cognitive impairments.

The findings show that simply 'boosting' the activity of the key memory and attention centres in the brain (the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex), which has been a long-standing strategy for cognitive enhancement, will not necessarily improve memory and attention, but can actually impair these functions. What's important is to re-balance activity within these regions.

Dr Bast, said: "One emerging idea is that early stages of cognitive disorders, such as schizophrenia and age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's, are characterised by faulty inhibition and too much activity; this excess neural activity leads then to neuronal damage and the reduced brain activity characterizing later stages of these disorders. So, rebalancing aberrant activity early on may not only restore attention and memory, but also prevent further decline.

"We have new studies on the way where we aim to identify medicines that might be able to re-balance neural activity within hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and to restore memory and attention."

Newswise — New Brunswick, N.J., –

Thanks to a two-year, $70,000 commitment from Embrace Kids Foundation, the Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center housed at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey is expanding to include a Pediatric Sickle Cell and Hemoglobinopathies Nurse Navigator position. The Center receives referrals from the state’s newborn screening program and from pediatricians in the central New Jersey region.

Sickle cell disease, an inherited disorder in which the red blood cells become hard and sticky, clogging the blood flow, affects approximately 100,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease, which can result in repeated episodes of severe pain, infections and anemia, occurs in one in every 365 African-American births and in one out of every 16,300 Hispanic-American births. Other affected populations include those whose ancestors are from Latin America, the Caribbean, Saudi Arabia, India, and Mediterranean countries.

The primary focus of the Pediatric Sickle Cell and Hemoglobinopathies Nurse Navigator is to enhance patient services, remove barriers to care, and improve care coordination. The nurse navigator supports the families of infants identified by newborn screening, beginning at the first point of contact, and facilitates communication between the family and care team. This includes collaborating with psychosocial counselors and service organizations to direct families to various resources. The navigator also educates families about their disease and treatment process including identifying clinical trials for which the patient may be eligible. And as adolescent patients begin to transition into an adult hematology care setting, the navigator plays a vital role in making sure the teenager is informed and connected to treatment and other resources.

Sickle cell disease is a lifelong condition that is marked by episodic medical setbacks. “The impact of this disease is disruptive to the family unit on many levels,” notes Embrace Kids Foundation Executive Director Glenn Jenkins. “The role of the Pediatric Sickle Cell and Hemoglobinopathies Nurse Navigator is integral in getting families back on track and returning a youngster to a normal childhood. Embrace Kids Foundation is pleased to be able to support this critical work in partnership with Jason and Devin McCourty through their Tackle Sickle Cell campaign.”

“Due to research and clinical advancements, the average life expectancy of babies born today with sickle cell disease has greatly improved, and many likely will live late into adulthood. However, this goal cannot be achieved unless medical care takes a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach with emphasis placed on prevention of long-term complications and timely treatment,” notes Richard Drachtman, MD, section chief, pediatric hematology/oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute and professor of pediatrics at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “With this commitment from Embrace Kids Foundation, we will be able to further empower patients and families with the knowledge and resources necessary to assume self-care to maximize longevity and quality of life. We thank Embrace Kids Foundation for its dedication to this population.”

About Rutgers Cancer Institute of New JerseyRutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (www.cinj.org) is the state’s only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. As part of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, the Cancer Institute of New Jersey is dedicated to improving the detection, treatment and care of patients with cancer, and to serving as an education resource for cancer prevention. Physician-scientists at Rutgers Cancer Institute engage in translational research, transforming their laboratory discoveries into clinical practice. To make a tax-deductible gift to support the Cancer Institute of New Jersey, call 848-932-8013 or visitwww.cinj.org/giving. Follow us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/TheCINJ.

The Cancer Institute of New Jersey Network is comprised of hospitals throughout the state and provides the highest quality cancer care and rapid dissemination of important discoveries into the community. Flagship Hospital: Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital. System Partner: Meridian Health (Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Ocean Medical Center, Riverview Medical Center, Southern Ocean Medical Center, and Bayshore Community Hospital). Affiliate Hospitals: JFK Medical Center, Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Hamilton (CINJ Hamilton), and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Somerset.

###

Newswise —

A study by Johns Hopkins researchers of more than 13,000 people has found that even after accounting for such risk factors as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes, so-called morbid obesity appears to stand alone as a standout risk for heart failure, but not for other major types of heart disease.

In a report on the research, published online on July 28 in theJournal of the American Heart Association, the Johns Hopkins team says morbidly obese individuals were more than two times more likely to have heart failure than comparable people with a healthy body mass index, after accounting for high blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar levels. And yet, after accounting for these factors, people with morbid obesity weren't any more likely to have a stroke or coronary heart disease -- basically disease of the heart's arteries," due in part to inflammation and an accumulation of plaque in the heart and surrounding blood vessels.

The researchers caution that their study suggests a strong, independent link between severe obesity and heart failure but does not definitively determine cause and effect.

Nevertheless, they say, their findings suggest that while treating hypertension, diabetes and other conditions associated with obesity may be sufficient to prevent coronary heart disease and stroke, this approach may not be enough to prevent an increased risk of heart failure, for which weight loss may be the only foolproof, currently available preventive measure. The federal government estimates that one in three Americans is obese and more than 5 percent are morbidly obese -- defined as a body mass index of greater than 35. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost 6 million people in the United States are living with heart failure, a condition of aging marked by enlarged and/or weakened heart muscle and diminished blood-pumping efficiency, resulting in shortness of breath, fatigue, weakness, trouble breathing when lying down, and swelling in the ankles and feet. Overall, there is a 50 percent mortality rate for people with heart failure five years after diagnosis.

"Obesity in our study has emerged as one of the least explained and likely most challenging risk factors for heart failure because there is no magic pill to treat it, no drugs that can easily address the problem like there are for high cholesterol and high blood pressure," says Chiadi Ndumele, M.D., M.H.S., assistant professor of medicine and member of the Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Even with diet and exercise, people struggle to lose weight and keep it off, and for the morbidly obese, the struggle is often insurmountable."

Although it isn't completely clear why obesity alone is linked to heart failure independent of risk factors and not to stroke or coronary heart disease, Ndumele says that there is evidence to suggest that extra body weight exerts a higher metabolic demand on the heart and that fat cells in the abdomen may even release molecules toxic to heart cells.

Obesity has long been known to increase the likelihood of high blood pressure, elevated blood cholesterol and diabetes -- all established risk factors for heart and blood vessel diseases. Treating and controlling these conditions have formed the bedrock strategies for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, Ndumele says.

To learn if this was truly the case for all types of cardiovascular disease, Ndumele and his colleagues looked at the medical records of 13,730 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study who had body mass indexes in healthy ranges or higher at the start of the study and no initial heart disease. The group was composed of 63.8 percent women and 16.9 percent African-Americans. The average age was 54, and body mass index ranged from 18 to 50. All were followed for approximately 23 years to assess links between body mass index and heart failure, coronary heart disease or stroke.

The records also included data for participants' height, weight, and levels of blood sugar, cholesterol and triglycerides, along with smoking status, alcohol use, professions and exercise levels. After the final participant follow-up in 2012, there were 2,235 recorded cases of heart failure, 1,653 cases of coronary heart disease and 986 strokes.

In their initial assessment, the Johns Hopkins researchers controlled for differences that might be due to age, sex, race, education level, career, smoking history, exercise and alcohol consumption. Severe obesity was associated with a nearly fourfold higher risk of heart failure and about a twofold higher risk for both coronary heart disease and stroke compared with rates for those with a normal body mass index.

Next, the researchers controlled for other heart disease risk factors, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. After this adjustment, Ndumele's team no longer saw an increase in risk for coronary heart disease or stroke in people with obesity. However, the increased risk for heart failure remained. For every five-unit higher body mass index, there was an almost 30 percent higher risk of developing heart failure across all participants.

"Even if my patients have normal blood sugar, cholesterol and blood pressure levels, I believe I still have to worry that they may develop heart failure if they are severely obese," says Ndumele. "If our data are confirmed, we need to improve our strategies for heart failure prevention in this population."