News

Newswise —

A computer model developed by scientists at the University of Chicago shows that small increases in transmission rates of the seasonal influenza A virus (H3N2) can lead to rapid evolution of new strains that spread globally through human populations. The results of this analysis, published September 13, 2016 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, reinforce the idea that surveillance for developing new, seasonal vaccines should be focused on areas of east, south and southeast Asia where population size and community dynamics can increase transmission of endemic strains of the flu.

“The transmissibility is a feature of the pathogen, but it's also a feature of the host population,” said Sarah Cobey, PhD, assistant professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Chicago and senior author of the study. “So a host population that potentially has more crowding, larger classroom sizes for children, or even certain types of social contact networks, potentially sustains higher transmission rates for the same virus or pathogen.”

There are four influenza strains that circulate in the human population: A/H3N2, A/H1N1, and two B variants. These viruses spread seasonally each year because of a phenomenon known as antigenic drift: They evolve just enough to evade human immune systems, but not enough to develop into completely new versions of the virus.

The H3N2 subtype causes the most disease each year. Genetic sequencing shows that from 2000 to 2010, 87 percent of the most successful, globally-spreading strains of H3N2 originated in east, south and southeast Asia. Cobey and her colleagues, lead author Frank Wen from the University of Chicago and Trevor Bedford of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, developed a computer model to simulate conditions in these areas.

The team used the model to test several hypotheses about why antigenically new, seasonal flu strains tend to emerge from this part of the world, including:

• Seasonality: 85 percent of Asia’s population lives in tropical or subtropical regions with no distinct winter, allowing continuous transmission of endemic flu strains and more opportunities for evolution of new strains. • Host population size: This area contains more than half of the world’s population. The sheer number of people could contribute a larger fraction of strains that spread globally.• Host population turnover: Birth rates have historically been higher in these areas than other temperate regions. This may contribute to a larger number of infants and young children who are more susceptible to the flu.• Initial conditions: H3N2 first emerged in Hong Kong in 1968. One hypothesis states that this gives the viral population an evolutionary head start, thus new epidemics will almost always begin in the area.• Transmission rates: Differences in the transmission rate of a given virus, or the expected number of secondary cases caused by a single infection, can affect the evolution of new strains.

Cobey and her colleagues simulated climate conditions, population dynamics and patterns of flu epidemics in these regions and found that only the transmission rate had a significant effect on the evolution of new strains that had the potential to spread globally. A transmission rate 17-28 percent higher in one region could explain historically observed patterns of flu epidemics.

“We basically find that increasing the transmission rate just a little bit greatly accelerates the rate at which antigenically novel strains can displace one another,” Cobey said.

Understanding how and why seasonal flu tends to originate in these areas reinforces the need for surveillance to identify new strains, not just in the affected parts of Asia, but other parts of the world with high-density populations, like west Africa. It also highlights how public health efforts to limit the spread of flu, namely widespread vaccination, can also limit the emergence of new strains.

Cobey said that while the team’s analysis focused initially on flu, it can also apply to any fast-evolving, human transmissible viruses like enteroviruses and colds.

“They spread from continent to continent over a pretty short time scale, so it will be exciting to see if we find similar patterns down the road once we have better surveillance of all these viruses,” she said.

The study, “Explaining the geographic origins of seasonal influenza A (H3N2)” was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

###

Newswise — PHILADELPHIA –

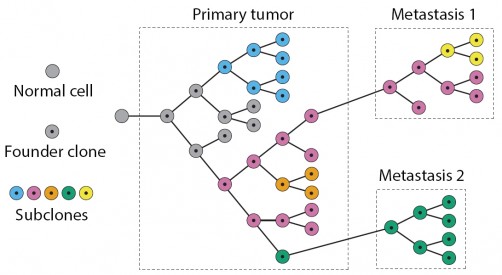

Individual cells within a tumor are not all the same. This may sound like a modern medical truism, but it wasn’t very long ago that oncologists assumed that taking a single biopsy from a patient’s tumor would be an accurate reflection of the physiological and genetic make-up of the entire mass.

Researchers have come to realize that cancer is a disease driven by the same “survival of the fitter” forces that Darwin proposed drove the evolution of life on Earth. In the case of tumors, however, individual cells are constantly evolving as a tumor’s stage advances. Mobile cancer cells causing metastasis are a deadly outcome of this process.

Tumors also differ among patients with the same type of cancer, so how is a physician able to prescribe a tailored regimen for the patient? To start to address this conundrum, an interdisciplinary team from the Perelman School of Medicine and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania developed Canopy, an approach to infer the evolutionary track of tumor cells by surveying two types of mutations – somatic copy number alterations and single-nucleotide alterations – derived from multiple samples taken from a single patient. They demonstrated the approach on samples from leukemia and ovarian cancer, along with samples from a human breast cancer cell line. Overall, the evolution of a tumor involves the accumulation of mutations of all types collectively influencing the fitness of tumor cells.

The team, Yuchao Jiang, a doctoral student in the Genomics and Computational Biology program, Yu Qiu, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of coauthor Andy Minn, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Radiation Oncology, and Nancy R Zhang, PhD, an associate professor of Statistics in the Wharton School, published their findings online in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The make-up of a tumor for a given patient is often a mixture of multiple distinct cell populations that differ in genetic make-up, gene expression, and physiology,” Jiang said. “This heterogeneity contributes to failures of targeted therapies and to drug resistance based on old thinking that tumors are homogenous masses.”

However, Canopy takes these differences into account because it uses data from multiple slices of the same tumor in space and time, as opposed to sampling in one spot at one time point, the way it is currently done in most sequencing studies. Canopy is an open-source software so oncologists will be able to use it to identify potential biomarkers for different cancer cell populations within tumor specimens that are associated with drug resistance and invasive malignancy, among other characteristics.

“Data input for Canopy from the clinic would come from tissue samples from the same patient - from normal tissue and from different places on the tumor and at different times,” Jiang said. “Canopy can then be used to infer the evolutionary history of the tumor to better understand how the tumor evolved and to find potential biomarkers.” The goal for Canopy is to help new patients at an early stage, using biomarkers to ascertain a correct diagnosis and prognosis.

The team also used animal models to refine their understanding of a metastasis model for breast cancer. After injecting human breast cancer cells into mice they observed where the primary breast cancer cells metastasized -- lung, bone, or other tissues. The site-specific metastatic samples, as well as the primary cancer cell lines were sequenced by whole-exome sequencing, from which somatic single-nucleotide alterations and copy number mutations were profiled. The relationships reconstructed by Canopy showed that, compared to the primary breast cancer cell lines, the metastatic samples from different organs had distinct genotypic patterns. Canopy identified metastasis-site-specific mutations for this specific malignant breast cancer cell line. The concept behind this proof-of-concept study can be applied to larger studies with the goal of identifying genomic changes that serve as prognostic markers for the development of distant metastasis.

By assigning mutation types to different parts of a tumor’s “evolutionary tree,” oncologists will be able to predict the site and severity of metastasis, and potentially, better courses of treatment. Applying Canopy to a larger cohort of samples is one of the team’s future directions.

In addition, says Zhang, recent advances in single-cell sequencing make possible the study of tumors at the single-cell level. However, reliable simultaneous profiling of copy number and single nucleotide mutations by single-cell sequencing is still in its infancy. “Our work shows that traditional bulk sequencing can lead to accurate tumor subclone identification, if the researcher is willing to sequence multiple slices of the tissue,” she said. “Bulk tissue sequencing can play an important part in our understanding of tumor heterogeneity, and in the coming years, experimental designs that combine bulk tissue sampling and single cell analysis need to be better explored.”

This work was funded by the NIH (R01-HG006137) and the PA Breast Cancer Coalition.

Newswise —

Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease are most likely to work if started early in the disease’s course, when amyloid plaques accumulate in the brain but memory is still intact. In their quest to recruit subjects in this preclinical disease state, clinicians must test people for AD risk factors such as brain amyloid accumulation or ApoE genotype, and then disclose that information to them so they can enroll in a trial. At the Alzheimer's Association International Conference, researchers presented early findings regarding the ethical, psychological, and societal impacts of such disclosure, and laid out their plans for the best ways to deliver the information. Cancer risk disclosure is more advanced, and guides their way. Beyond clinical trials, having smart disclosure procedures in place will be crucial if an AD therapy is approved, as then scores of people will want to get tested to head off the disease. Jessica Shugartexamines the dilemma.

About UsFounded in 1996, Alzforum is a news and information resource website dedicated to helping researchers accelerate discovery and advance development of diagnostics and treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.

Our site expands the traditional mode of scientific communication by reporting the latest scientific findings and industry news with insightful analysis that puts breaking news into context. We advance research by developing open-access databases of curated, highly specific scientific content to visualize and facilitate the exploration of complex data. Alzforum is a platform to disseminate the evolving knowledge around basic, translational, and clinical research in the field of AD.

Alzforum is supported by a team with backgrounds in science, journalism, information technology, design, and data science. Together with a distinguished Scientific Advisory Board, and the active participation of a global network of scientists, we strive to produce unbiased content to a rigorous editorial standard.

Alzforum is operated by the Biomedical Research Forum (BRF) LLC. BRF is a wholly owned subsidiary of FMR LLC. FMR LLC and its affiliates invest broadly in many companies, including life sciences and pharmaceutical companies. Alzforum does not endorse any specific product or scientific approach.

Newswise — BOSTON —

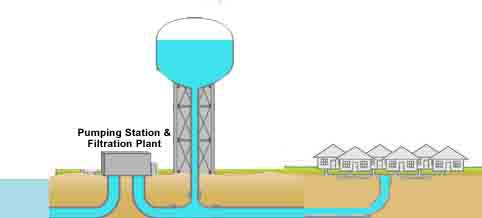

A new analysis of 100 million Medicare records from U.S. adults aged 65 and older reveals rising healthcare costs for infections associated with opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens—disease-causing bacteria, such as Legionella—which can live inside drinking water distribution systems, including household and hospital water pipes.

A team led by researchers from the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University and Tufts University School of Medicine found that between 1991 and 2006, more than 617,000 hospitalizations related to three common plumbing pathogens resulted in around $9 billion in Medicare payments—an average of $600 million a year. The costs may now exceed $2 billion for 80,000 cases per year, write the study authors. Antibiotic resistance, which can be exacerbated by aging public water infrastructure, was present in between one and two percent of hospitalizations and increased the cost per case by between 10 to 40 percent.

“Premise plumbing pathogens can be found in drinking water, showers, hot tubs, medical instruments, kitchens, swimming pools—almost any premise where people use public water. The observed upward trend in associated infections is likely to continue, and aging water distribution systems might soon be an additional reservoir of costly multidrug resistance,” said lead study author Elena Naumova, Ph.D., professor at the Friedman School and Director of the Initiative for the Forecasting and Modeling of Infectious Disease at Tufts University. “This is a clear call for deepened dialogue between researchers, government agencies, citizens, and policy makers, so that we can improve data sharing and find sustainable solutions to reduce the public health risks posed by these bacteria.”

The study was published in the Journal of Public Health Policy on Sept. 12.

State and federal oversight has ensured generally safe and good quality public drinking water in the U.S. However, premise plumbing systems—the pipes and fixtures in homes and buildings that transport water after delivery by public water utilities—are largely unregulated, which can lead to inconsistent monitoring and reporting of potentially harmful deficiencies. This is highlighted by the ongoing crisis in Flint, Michigan, where a water source change, aging pipes, and lack of corrosion control not only exposed thousands of children to elevated lead levels in drinking water, but is also thought to have triggered an outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease that led to 10 deaths.

Opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens, such as the bacteria that causes Legionnaire’s disease, Legionella pneumophila, can thrive in low-nutrient conditions and grow as biofilms on the inner surfaces of pipes. Biofilms allow these pathogens to resist disinfectants and environmental stressors, and aid in the spread of antibiotic resistance and virulent genes. As water distribution systems age, their susceptibility to contamination increases. However, few large-scale studies have examined the economic and public health burden of these bacteria.

To investigate, Naumova and her colleagues analyzed 100 million medical claims from 1991 through 2006 from the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which provides exhaustive coverage of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older. The team focused on hospitalizations related to three opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can cause a range of serious respiratory, systemic, or localized infections, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly or immunocompromised individuals.

Based on clinical diagnostic codes, reported cases for all three infections totaled 617,291, with the majority due to pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas and related bacteria (560,504). Legionnaire’s disease and Mycobacteria infections accounted for 7,933 and 48,854 cases respectively. On average, each hospitalization represented $45,840 in Medicare charges and $14,920 in payments. Antibiotic resistance, recorded in a little under two percent of cases, increased the average costs to $60,870 in Medicare charges and $16,690 in payments per case.

Over the past decade, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a substantial increase in incidence of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens, with Pseudomonas alone accounting for 51,000 hospitalizations per year with more than 6,000 multi-drug resistant infections in 2011. The annual costs for these pathogens may now exceed a total of $2 billion for more than 80,000 cases per year, as increased antibiotic resistance leads to greater hospital charges, longer lengths of stay, and increased risk of complications. Antibiotic resistance is likely underreported, and this number is a conservative estimate for the Medicare population based on the study findings and reported data on hospitalization costs per case, says Naumova.

“While public drinking water is safe, it is clearly more safe if you are healthy than if you have medical conditions that enhance your vulnerability to infections. The risk of becoming ill from drinking water is much less than the risk of becoming ill from food, but it is not zero,” said last author Jeffrey K. Griffiths, M.D., professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine. Griffiths is also former chair of the Drinking Water Committee for the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Science Advisory Board. “These infections can cause a lot of illness and cost us a lot of money, and targeted disinfection of premise piping could save us from these consequences.”

The authors caution that their data cannot draw conclusions about the percentage of infections directly caused by contaminated water. The link between aging water distribution systems and drug resistance is highly plausible, but has yet to be firmly established, say the authors. However, this study highlights the need for improved surveillance systems and targeted investigations of water-related outbreaks in order to determine the direct link between water contamination and drug-resistant infection.

A 2010 report from the national Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System, a partnership between the Centers for Disease Control, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, urged serious attention to be paid to the growing proportion of outbreaks associated with premise plumbing deficiencies in public water systems. However, budgets for state and federal water regulators have decreased. In 2013, the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators reported that "federal officials had slashed drinking-water grants, 17 states had cut drinking-water budgets by more than a fifth, and 27 had cut spending on full-time employees," with "serious implications for states’ ability to protect public health.”

“The Flint Water Crisis revealed many unsolved social, environmental, and public health problems for US drinking water,” Naumova said. “Unfortunately, water testing for pathogens is not done routinely; furthermore, most water tests are not accessible, are too complicated, or are too costly. Well-controlled, experimental studies of the influence of microbial ecology, disinfectant type, pipe materials, and water age, on opportunistic pathogen occurrence and persistence are needed in order to establish their relationships to drug resistance.”

##

Additional authors on this study are Alexander Liss, M.B.A., Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in the School of Engineering at Tufts University, Jyotsna S. Jagai, M.S., M.P.H., Ph.D., assistant professor in the Division of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Irmgard Behlau, M.D., research assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Biology and Microbiology at Tufts University School of Medicine.

This study was in part supported by awards from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES013171) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI062627 and AI050032), both of the National Institutes of Health.

Naumova, EN, Liss, A, Jagai, JS, Behlau, I, Griffiths, JK, “Hospitalizations due to selected infections caused by opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens (OPPP) and reported drug resistance in the United States older adult population in 1991-2006,” Journal of Public Health Policy. 2016.

About the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and PolicyThe Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University is the only independent school of nutrition in the United States. The school's eight degree programs – which focus on questions relating to nutrition and chronic diseases, molecular nutrition, agriculture and sustainability, food security, humanitarian assistance, public health nutrition, and food policy and economics – are renowned for the application of scientific research to national and international policy.About Tufts University School of Medicine and the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical SciencesTufts University School of Medicine and the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences are international leaders in medical and population health education and advanced research. Tufts University School of Medicine emphasizes rigorous fundamentals in a dynamic learning environment to educate physicians, scientists, and public health professionals to become leaders in their fields. The School of Medicine and the Sackler School are renowned for excellence in education in general medicine, the biomedical sciences, and public health, as well as for innovative research at the cellular, molecular, and population health level. The School of Medicine is affiliated with six major teaching hospitals and more than 30 health care facilities. Tufts University School of Medicine and the Sackler School undertake research that is consistently rated among the highest in the nation for its effect on the advancement of medical and prevention science.

Newswise — DURHAM, N.C. –

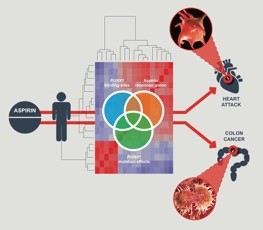

Aspirin’s ability to reduce the risk of both cardiovascular disease and colon cancer has been a welcome, yet puzzling, attribute of the pain reliever that has been a mainstay in medicine cabinets for more than 100 years.

Now researchers at Duke Healthhave identified a new mechanism of aspirin’s action that appears to explain the drug’s diverse benefits.

Publishing in the journalEBioMedicine, the researchers describe how aspirin directly impacts the function of a gene regulatory protein that not only influences the function of platelets, but also suppresses tumors in the colon.

“This research identifies a new way in which aspirin works that was not predicted based on the known pharmacology,” said lead author Deepak Voora, M.D., assistant professor in Duke’s Center for Applied Genomics & Precision Medicine. Voora said aspirin’s pain-reducing and blood thinning powers have long been traced to its ability to block COX-1, an enzyme involved in both inflammation and blood clotting.

“But COX-1 has only partially explained how aspirin works for cardiovascular health,” he said, “and it has not been shown to be implicated in cancer at all.”

Instead, Voora and colleagues focused on a pattern of gene activity they call an aspirin response signature the team had previously developed. The signature identified a network of genes that correlated with platelet function and heart attack.

“This approach to comprehensively evaluate the actions of a drug using genomic data -- as we have done here with aspirin -- is a paradigm shift that could change how drugs are developed and positioned for clinical use, said co-author Geoffrey Ginsburg, M.D., director of the Center for Applied Genomics & Precision Medicine. “We intend to use this approach to explore the pleiotropic effects of drugs more broadly to anticipate their side effects and understand their full repertoire of actions clinically.”

In addition to Voora and Ginsberg, study authors from Duke include Rachel Myers, Emily Harris and Thomas L. Ortel. They were joined by A. Koneti Rao and Gauthami S. Jalagadugula of Temple University.

The National Institute of Health provided grant funding (RC1GM091083, R01HL109568, R01HL118049).

###

Newswise —

Living a heart healthy lifestyle is not about doing just one thing. Other steps are important too.

“Diet, exercise and even a positive attitude are all factors that can help you avoid heart disease,” says Dr. Sheila Sahni, an interventional cardiology fellow at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

How to get started? Begin with small, incremental changes, Sahni says.

Eat well. Go for nutrient-rich foods from a wide range of food groups. Focus on eating meals or snacks with high-protein such as white meat, fish, eggs, low-fat milk and soy. Good fats are OK. These include avocado, nuts and peanut butter. Don’t forget to eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables a day.

When it comes to starches, stick to complex carbohydrates such as whole grains, beans and most vegetables. They’ll keep you feeling full for a longer period of time.

The best fish for heart health are firm, fatty, cold-water fish like salmon, halibut and tuna. These have the highest levels of heart healthy omega 3 fats. If you don’t like fish, use fish oil supplements.

Limit or avoid certain foods. Saturated fat and trans fat can increase cholesterol, which can harm your heart. These are commonly found in margarines, partially hydrogenated vegetables fats, processed and fast foods.

Red meats taste great but are associated with worse health outcomes. Choose white meat such as chicken or pork.

Sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages and refined grains like white rice, white bread or sweetened cereals are associated with more weight gain and worse health outcomes. Instead, eat whole grain foods such as brown rice, whole wheat bread and oatmeal.

Burn those calories throughout the day. Exercise is key! Taking the stairs, walking while you’re on the phone, parking further away at the shopping center or work can help you get more exercise. The American Heart Association recommends 150 minutes of moderately intense exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous activity each week. Intensity is defined relative to an individual’s capacity, but some examples of moderate intensity activity are walking briskly, water aerobics, ballroom dancing and gardening. Some examples of vigorous intensity activity include swimming laps, jumping rope, race walking or jogging, or hiking uphill. Remember that you are in control of how you fit movement into your daily schedule.

Be optimistic!Optimism has been shown to be associated with better health. Many studies have shown that heart patients with a healthier psychological state have better outcomes. And people with a positive outlook tend to have better health behaviors, which tend to lead to better overall health outcomes.

Know your heart’s health.The best way to know if you’re “heart healthy” is to see your doctor for a physical examination to determine any heart disease risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol or a family history of premature heart disease or diabetes.

“Once you know your risk factor profile, you can gauge your health by getting those risk factors under control,” says Dr. Gaurav Banka, a clinical cardiology fellow at UCLA. “For instance, if you have high blood pressure and you start to exercise and your blood pressure decreases, you know you’re moving in the “heart healthy” direction. Risk factor control and management is the optimum way to care for your heart because it’s a preventive measure against heart disease.”

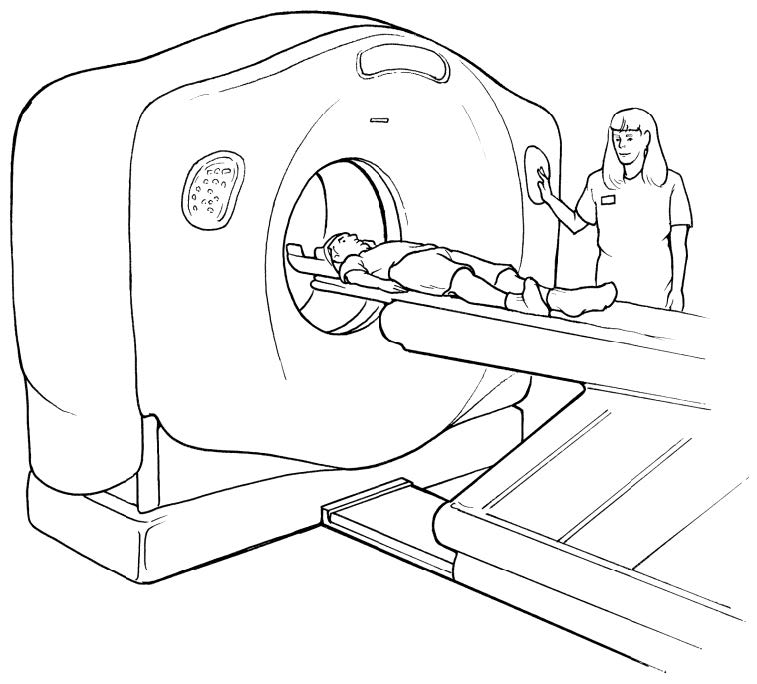

Newswise — Hospitals on average charged more than 20 times their own costs in 2013 in their CT scan and anesthesiology departments ― suggesting that hospitals strategically use “chargemaster” markups to maximize revenue, according to new research from Johns Hopkins University.

Appearing in the September issue of Health Affairs, the study notes that many hospital executives say the chargemaster prices determined by individual hospitals for billable items are irrelevant to patients.

However, the relation between chargemaster markups and hospital revenue and the variation in markups across hospitals and departments show that the hospitals are still using their chargemaster markups to enhance revenues, say the study’s authors, Ge Bai of the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School and Gerard F. Anderson of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“Hospitals apparently mark up higher in the departments with more complex services because it is more difficult for patients to compare prices in these departments,” states lead author Bai, a Carey Business School assistant professor whose expertise is in accounting issues within the health care industry.

As the chart below indicates, average charge-to-cost ratios for hospital departments vary from a low of 1.8 for inpatient general routine care to a high of 28.5 for computed tomography (CT) scan, with anesthesiology right behind at 23.5. This means that a hospital whose costs in the CT department are $100 will charge a patient without health insurance and an out-of-network privately insured patient $2,850 for a CT scan.

Anderson, a professor in the Bloomberg School’s Department of Health Policy and Management, says the impact of hospital markups is vast: “They affect uninsured and out-of-network patients, auto insurers and casualty and workers’ compensation insurers. The high charges have led to personal bankruptcy, avoidance of needed medical services, and much higher insurance premiums.”

Hospitals with strong market power, through either system affiliations or dominance of regional markets, were more likely to set high markups, as revealed by financial data in 2013 collected by the authors from all Medicare-certified hospitals with more than 50 beds.

In their paper, the authors examine the average hospital’s overall charge-to-cost ratio, which expresses the ratio of what the hospital charged compared to the hospital’s actual medical expense. In 2013, the average hospital with more than 50 beds had a charge-to-cost ratio of 4.32 ― that is, the hospital charged $4.32 when the cost was only $1.

However, certain types of hospitals had higher markups. In government-run hospitals, the ratio was 3.47; in nonprofit hospitals, 3.79; and in for-profit hospitals, 6.31. System-affiliated hospitals had an average ratio of 4.76, versus 3.54 for independent hospitals, and hospitals with regional market power had an average ratio of 4.56, versus 4.16 for hospitals that lacked such clout ― supporting the researchers’ finding that hospitals that can mark up prices will do so. The markups help their bottom lines; a one-unit increase in markup, such as from 3.0 to 4.0, is linked with a $64 higher revenue per adjusted discharge.

Besides the setting of a cap on the maximum markup hospitals can charge, Bai and Anderson recommend two solutions to high markups. First, improve the transparency of markups by requiring hospitals to provide a benchmark rate, such as what Medicare would pay for the same services, on all medical bills so that patients can compare the amounts, while also requiring hospitals to disclose the total charges as a separate line item on their annual income statements. Second, improve the consistency of the charge-to-cost ratios across all departments and services within each hospital.

“Mandatory disclosure on medical bills and financial statements will be an important step toward markup transparency,” says Bai.

“We realize that any policy proposal to limit hospital markups would face a very strong challenge from the hospital lobby,” says Anderson, “but we believe the markup should be held to a point that’s fair to all concerned ― hospitals, insurers, and patients alike.”

“US Hospitals Were Still Using Chargemaster Markups to Maximize Revenues In 2013” was written by Ge Bai and Gerard F. Anderson and appears in the September 2016 issue of Health Affairs.------ Average Charge-to-Cost Ratios for Selected Hospital Patient Care Departments, 2013

RANK DEPARTMENT CHARGE-TO-COST RATIO*1 Computed tomography scan 28.52 Anesthesiology 23.53 Magnetic resonance imaging 13.64 Electrocardiology 12.4 5 Electroencephalography 9.36 Cardiac catheterization 8.77 Laboratory 8.58 Medical supplies charged to patients 8.39 Radioisotope 7.210 Renal dialysis 6.511 Radiology-diagnostic 6.412 Drugs charged to patients 5.913 Emergency 5.714 Respiratory therapy 5.515 Recovery room 5.316 Operating room 5.117 Occupational therapy 5.018 Speech pathology 4.819 Labor room and delivery room 4.420 Implantable device charged to patients 3.621 Clinic 3.022 Physical therapy 3.023 Nursery 2.724 Intensive care unit 2.125 Inpatient General routine care 1.8

* Charge-to-cost ratio is the dollar charge for every $1 of actual patient care cost incurred by the hospital. For example, a ratio of 7.2 means a hospital charge of $7.20 for every dollar of actual patient care cost.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from Medicare cost reports and Final Rule Data obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2013.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

With nearly sixty percent of American adults now taking prescription medications—from antidepressants to cholesterol treatments—there is growing concern about how many drugs are flowing through wastewater treatment facilities and into rivers and lakes. Research confirms that pharmaceutical pollution can cause damage to fish and other ecological problems—and may pose risks to human health too.

Scientists have assumed that people flushing their unused medications down the drain or toilet was a major source of these drugs in the water.

But a new first-of-its-kind study tells a different story.

“Less than one percent of students we surveyed report flushing any drugs down the drain in the last year,” says University of Vermont scientist Christine Vatovec. And what she and her colleagues found in the water backs up the students’ self-reporting.

In Burlington, Vermont, Vatovec co-led a team of five scientists from the University of Vermont and the United States Geological Survey who sampled wastewater outflow for ten days during the spring when students from UVM and Champlain College were moving out. They detected fifty-one pharmaceuticals pouring into Lake Champlain—and they expected to see a spike in concentrations of some of these drugs as students dumped unused meds down the drain while they were departing their dorm rooms and apartments. But they didn’t see it.

Concentrations of caffeine and nicotine decreased slightly after the students left (no surprise), but there was no data suggesting that students were flushing their unwanted medications. Many students reported having leftover prescription meds, but only a small portion of them disposed of these drugs, mainly in the trash.

“This contradicts the common assumption that down-the-drain disposal is an important source of pharmaceuticals to the wastewater stream in the environment,” the team writes in their study, published August 29 in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

A surprise

“Our study is the first time that scientists have correlated data about how people are purchasing, using and disposing of their pharmaceuticals with data on what's actually coming down the pipe,” Vatovec says. Several surveys in recent decades indicated that a majority of Americans flush unfinished or unwanted medications. But the new study found a very different result in its survey of more than 300 students. “Flushing does not appear to be an important source,” says Patrick Phillips, a hydrologist with the US Geological Survey who co-led the new study. “I was surprised.”

The scientists did detect a rise in allergy medications in the water that correlated to a rise in seasonal pollen. They also saw a relative rise in drugs used by older people—like diabetes and heart medications—after the younger people moved out.

Current advice encourages people to take unneeded medications to drop-off days at police stations and pharmacies so they can be incinerated, and almost none of the students indicated that they were in the habit of tossing unwanted meds down the drain. However, some people who were, in earlier decades, encouraged to flush may still be doing that. “So we have more to learn about other parts of the population,” Vatovec says, but education efforts with students may not be the best investment since excretion and other sources of drugs, like pharmaceutical manufacturing, appear to be much more important sources of drugs in wastewater.

Safe to drink

Vatovec—who holds a joint faculty appointment in UVM's Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources and the College of Medicine—is quick to note that there is no evidence that the extremely low concentrations of pharmaceuticals found in their survey and other similar studies pose any direct risk to human health.

“These results should not make people nervous about swimming or drinking water,” she says, “because, to the best of scientific knowledge we have available right now, the concentrations are so low that you’d need to drink about the football field’s worth of lake water to get an actual dose of any one individual pharmaceutical.” And the team’s results in Burlington for Lake Champlain are not unusual. “Pharmaceuticals are found in about eighty percent of the surface waters tested in the United States,” Vatovec says.

Which is one reason why she is eager to see the development of practices to help people manage their health with fewer medications—and to see the development of “green pharmacy” drugs that fully break down in the body. “We know these drugs in our surface waters can create ecological problems and there are more and more of them,” she says. Though there is no evidence yet that human health is threatened by pharmaceutical pollution, “there are many unanswered questions,” she says.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — CLEVELAND –

Case Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers, a research collaboration which includes University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center and Case Western Reserve University, who last year identified new gene mutations unique to colon cancers in African Americans, have found that tumors with these mutations are highly aggressive and more likely to recur and metastasize. These findings partly may explain why African Americans have the highest incidence and death rates of any group for this disease.

The study is published online (http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/108/12/djw164.full.pdf+html) and will be printed in the December 2016 issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI) by members of a research team that a year ago found 15 genes in African Americans that are rarely or never detected as mutated in colon cancers from Caucasians. The current study investigated the outcomes associated with these mutations in African American colorectal cancer.

The researchers examined 66 patients who had stage I – III colorectal cancer and found those patients positive for the mutations had an almost three times higher rate of metastatic disease, and stage III patients positive with mutations were nearly three times more likely to relapse compared to patients without the mutations.

“This study is significant because it helps shed further light on why colorectal cancers are more aggressive in African Americans compared to other groups,” said the study’s senior author Joseph E. Willis, MD, Chief of Pathology at University Hospitals Case Medical Center and Professor of Pathology at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. “While mortality rates for Caucasian men with colorectal cancer have decreased by up to 30 percent, they have increased by 28 percent for African American men since 1960,” said Dr. Willis, who is also director of tissue management in the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center.

These findings and the earlier study only became possible because of technological advances in gene sequencing and computational analysis. These studies ultimately involved review of 1.5 billion bits of data.

“This study builds on our previous genetic research on colorectal cancer,” said Sanford Markowitz, MD, PhD, a co-author and principal investigator of the $11.3 million federal gastrointestinal cancers research program (GI SPORE) that includes this project. ”It illustrates the extraordinary impact that dedicated, collaborative teams can make when they combine scientific experience and ingenuity with significant investment.”

Announced in 2011, this GI SPORE program is one of just five in the country. Dr. Markowitz, Ingalls Professor of Cancer Genetics at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and a medical oncologist at UH Seidman Cancer Center, included studies of the disease’s behavior in minority patients as part of his team’s original grant application. The disparity between colorectal cancer rates in African Americans and other groups has long existed; the most recent federal statistics, for example, put age-adjusted incidence at 46.8 cases for every 100,000 African Americans, and 38.1 cases for every 100,000 Caucasian Americans. Yet scientists have struggled to determine what factors — biological, economic, environmental, or others — account for this disparity.

From the very start, Dr. Markowitz and colleagues believed the answer to this question would be found through genetic analysis.“Identifying gene mutations has been the basis of all the new drugs that have been developed to treat cancer in the last decade,” Dr. Markowitz said. “Many of the new cancer drugs on the market today were developed to target specific genes in which mutations were discovered to cause specific cancers.”

“We wondered if colon cancer is the same disease molecularly in African American individuals as it is in Caucasian individuals. Or could colon cancer be the same disease behaving differently in one population compared to another,” he said. “This study gave us our answer. Colon cancer in African American patients is a different disease molecularly.”

The scientists made their discovery by using DNA sequencing to compare 103 colorectal cancer samples from African American patients with 129 colorectal cancer samples from Caucasian patients, all of whom had received care at UH Case Medical Center in Cleveland. The scientists examined 50 million bits of data from 20,000 genes in every cancer.

This research was supported by Public Health Service Awards Case GI SPORE P50 CA150964 and KO8 CA148980 and Career Development Program of Case GI SPORE Awards P50 CA150964; R21 CA149349, and P30 CA043703. Substantial and generous gifts also came from the Marguerite Wilson Foundation, the Leonard and Joan Horvitz Foundation, and the Richard Horvitz and Erica Hartman-Horvitz Foundation.

Other collaborating authors for this paper were Zhenghe Wang, PhD; Li Li, MD, PhD; Kishoe Guda, PhD; Zhengyi Chen, PhD; Jill Barnholtz-Sloan, PhD; and Young Soo Park, PhD.# # #

Newswise —

Heavy drinking frequently causes liver inflammation and injury, and fatty acids (FAs) involved in pro- and anti-inflammatory responses could play a critical role in these processes. This study evaluated heavy drinking and changes in levels of omega-6 (ω-6, pro-inflammatory) and omega-3 (ω-3, anti-inflammatory) FAs in alcohol dependent (AD) patients who showed no clinical signs of liver injury.

Researchers assigned 114 heavy drinking AD patients recruited from an AD treatment program to one of two groups based on the levels of a specific liver enzyme, alanine aminotransferase--ALT, elevated levels of which reflect liver injury. The patients were aged 21–65 years and showed no signs of liver injury. Patient group one (34 males, 24 females) had normal levels of ALT and patient group two (40 males, 16 females) had mildly elevated ALT levels.

Results indicated that changes in the ω-3 and ω-6 FA levels and the ω-6:ω-3 ratio reflected a pro-inflammatory shift in patients with elevated ALT—mild liver injury. At comparable levels of alcohol consumption, women in the study showed greater liver injury than men. The authors speculated that women may be at greater risk of developing alcoholic liver disease than men, even when consuming less alcohol.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY