News

Newswise — BIRMINGHAM, Ala. –

February is American Heart Month, and it is an important time to be informed on the most beneficial foods and nutrients to maintain a heart-healthy diet.

According to the American Heart Association, heart disease is the leading global cause of death; 2,200 Americans die each day from heart disease. Wholesome nutrition is a major factor in combating plaque build-up in coronary arteries, which results in the most common type of heart disease, coronary artery disease. The AHA encourages limiting “sugary drinks, sweets, fatty or processed meats, solid fats, and salty or highly processed foods” to maintain a heart-healthy diet.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that a poor diet — among diabetes, obesity, physical inactivity and excessive alcohol use — is one of the most influential lifestyle choices that put people at a higher risk for heart disease. Americans are advised by organizations such as the CDC and the AHA to consume more fruits and vegetables and less sodium and sugar.

Carleton Rivers, RDN, assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition Sciences in the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and program director of the UAB Dietetic Internship, is an expert on dieting and nutrition. She says eating fresh fruits and vegetables cooked using a low-fat method are great for heart health.

“Choose vegetables that have a rich color like dark leafy greens, sweet potatoes, squash, carrots and zucchini,” Rivers said. “Just be sure not to substitute fresh fruits with 100 percent fruit juice or dried fruit.”

Fruit juice and dried fruit are high in sugar and may be consumed in a greater amount than a whole piece of fruit. Fruit juices also lack the fiber needed to control blood sugar.

Rivers says fiber and protein are important.

“Fiber is important for gastrointestinal motility, blood sugar control and lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol,” Rivers said. “Fiber is great for appetite control because it can fill you up and keep you feeling fuller for longer.”

She says protein is needed to build and maintain muscles and can be found in a variety of sources such as lean meats cooked using a low-fat method, such as baking.

The AHA and CDC advise cooking meals at home to have a healthy, balanced diet, and Rivers agrees it may be easier to eat healthy when one cooks or prepares meals at home.

“Many restaurants add butter and salt to improve the taste of dishes,” Rivers said. “This of course increases the calorie amount for a meal. Before going to a restaurant, look up the nutrition facts for the menu items you think you would want to eat, then make a decision based on which menu items are lower in calories, saturated fat, sodium and sugar.”

As much as the AHA and the CDC encourage a heart-healthy diet, Rivers says a “cheat day” is OK every now and then to allow yourself to have a little bit of what you are craving to help prevent derailing from a diet all together.

Your favorite piece of chocolate or guacamole and tortilla chips are what Rivers recommends as two heart-healthy treats to have on those “cheat days.”

“The occasional bite of dark chocolate or a nice glass of pinot noir is a perfect reward for your efforts to sustain your heart health.”

To find heart-healthy recipes and recommendations, visit the UAB Heart and Vascular Services recipe website.

Newswise —

While obesity is often thought of as a health problem, a new study by a University of Illinois at Chicago sociologist suggests that discrimination by body weight may be the more important factor for obese white female students' lower success in school.

The study, published in the latest issue of the journal Sociology of Education, indicates that the relationship between obesity and academic performance may result largely from educators interacting differently with girls of various sizes, rather than from obesity's effects on girls' physical health.

Even when they scored the same on ability tests, obese white girls received worse high school grades than their normal-weight peers. Teachers rated them as less academically able as early as elementary school, according to the report's author, Amelia Branigan, UIC visiting assistant professor of sociology.

Branigan analyzed elementary school students around age 9 in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, and high school students approximately 18 years old in the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997 cohort. The elementary school students were evaluated by teacher-assessed academic performance, while grade point average was the measured outcome used to assess the high school students.

The study found obesity to be associated with a penalty on teacher evaluations of academic performance among white girls in English, but not in math. There was no penalty observed for white girls who were overweight but not obese.

"Obese white girls are only penalized in 'female' course subjects like English," Branigan said. "This suggests that obesity may be most harshly judged in settings where girls are expected to be more stereotypically feminine."

Consistent with prior work on obesity and wages and other academic outcomes, no similar association was found in either math or English for white boys, or for black students of either sex. This may reflect findings that obesity is more stigmatized among white women than among white men or individuals of other races, according to Brannigan, who says social interventions for teachers may lessen the performance gap.

"As we continue to combat childhood obesity, efforts to also counter negative social perceptions of obese individuals would have advantages in terms of both educational outcomes and social equity more generally," she said.

The study, "(How) Does Obesity Harm Academic Performance? Stratification at the Intersection of Race, Sex, and Body Size in Elementary and High School," was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Newswise — WASHINGTON —

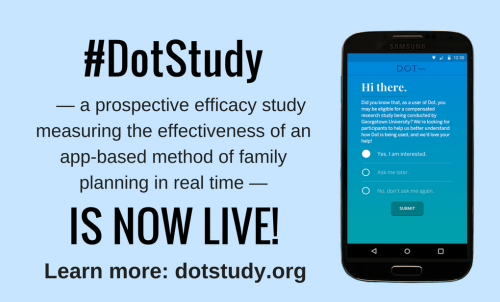

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center’s Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH) announced today the launch of a year-long study to measure the efficacy of a new app, Dot™, for avoiding unintended pregnancy as compared to efficacy rates of other family planning methods. The Dot app, available on iPhone and Android devices, is owned by Cycle Technologies. Up to 1,200 Dot Android users will have the opportunity to participate in the study.

The study, funded by a grant from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), will be the first known study to examine how women use a fertility app in real-time and to evaluate its effectiveness at avoiding unintended pregnancy. In a previous study, a research team found that Dot is theoretically 96 to 98 percent effective at avoiding unintended pregnancy if used correctly. As a woman continues to use it, the app increases its individual accuracy.

While there are thousands of menstrual cycle tracking apps on the market, recent research has demonstrated that the majority are not accurate enough to avoid unintended pregnancy or plan a pregnancy. One study evaluated 100 fertility awareness apps. Only six could correctly identify the fertile window. This finding highlights the importance for app-based family planning tools to rely on scientifically-backed methods and to be evaluated thoroughly for their accuracy.

“Our new study is unique because we’re testing the efficacy of Dot as a method to avoid unplanned pregnancy in a real-time situation,” says Rebecca Simmons, PhD, a senior research officer at IRH.

The study will evaluate Dot’s efficacy in avoiding unplanned pregnancies using a protocol that allows researchers to compare the results to known efficacy rates of other family planning options. It will also explore social factors, such as how Dot affects relationships. The researchers will recruit participants through Dot for Android, issue surveys in the app, and interview participants four times during the study. Participants will receive a gift card each time they enter period start date information and each time they complete a survey.

The IRH study could have global significance because multiple studies suggest that the main reason women stop using the birth control pill is side effects. If Dot can help women avoid pregnancy without the pill’s high abandonment rate, it’s a compelling alternative, says Simmons. The app would be especially useful in the developing world, where there is significant unmet family planning need. Global health experts estimate that 225 million women worldwide are not using effective family planning methods but want to avoid pregnancy.

“Dot users have a historical opportunity to advance the science of birth control and family planning,” said Leslie Heyer, president and founder of Cycle Technologies. “No fertility app has undergone such rigorous testing. Users who join our effort can help make free, effective fertility tools accessible to women throughout the world.”

Cycle Technologies developed the science and algorithm behind Dot™ in collaboration with global health experts from Georgetown University, Duke University and The Ohio State University. Dot is the only family planning app that relies solely on period start dates to determine a user’s individual fertile days.

“A method that only requires a user to enter her period start date is likely to appeal to many women,” said IRH’s Director, Victoria Jennings, PhD. “Our work has shown that simple fertility awareness messages are extremely attractive to a wide range of women and can address their family planning needs.”

About the Institute for Reproductive HealthThe Institute for Reproductive Health at Georgetown University Medical Center has more than 25 years of experience in designing and implementing evidence-based programs that address critical needs in sexual and reproductive health. The Institute’s areas of research and program implementation include family planning, adolescents, gender equality, fertility awareness, and mobilizing technology for reproductive health. The Institute is highly respected for its focus on the introduction and scale-up of sustainable approaches to family planning and fertility awareness around the world. For more information, visit www.irh.org.

About Georgetown University Medical CenterGeorgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC’s mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization, which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health. Connect with GUMC on Facebook (Facebook.com/GUMCUpdate), Twitter (@gumedcenter) and Instagram (@gumedcenter).

Newswise — EAST LANSING, Mich. —

Michigan State University researchers are the first to uncover reasons why a specific type of immune cell acts very differently in females compared to males while under stress, resulting in women being more susceptible to certain diseases.

The novel finding could be considered a good example of the pop culture metaphor that men and women are from two distinct planets and respond very differently under stressful situations.

Led by Adam Moeser, an endowed chair and associate professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine, the federally funded study found that females were more vulnerable to certain stress-related and allergic diseases than males because of distinct differences found in mast cells, a type of white blood cell that’s part of the immune system.

“Over 8,000 differentially expressed genes were found in female mast cells compared to male mast cells,” Moeser said. “While male and female mast cells have the same sets of genes on their chromosomes, with the exception of the XY sex chromosomes, the way the genes act vary immensely between the sexes.”

The study is co-authored by Emily Mackey, a doctoral student in veterinary medicine, and is published in the journal Biology of Sex Differences.

Mast cells are an important immune cell because they play a key role in stress-related health issues that are typically more common in women such as allergic disorders, autoimmune diseases, migraines and irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS.

IBS, for example, is a disorder in the intestine that creates significant abdominal pain and affects almost a quarter of the U.S. population. Women are up to four times more likely to have it than men. A further in-depth analysis of the genes within the RNA genome – a primary building block in all forms of life – revealed an increase in activity that’s linked to the production and storage of inflammatory substances. These substances can create a more aggressive response in the body and result in disease.

“This could explain why women, or men, are more or less vulnerable to certain types of diseases,” Moeser said.

With this new understanding of how different genes act, Moeser said scientists could eventually start developing new sex-specific treatments that target these immune cells and stop the onset of disease.

He added though that an important next step in his research is figuring out when in the development stage these immune cells start to act differently.

“Pinpointing when this variance happens will let us know if it occurs during adulthood or in individuals at an early age,” Moeser said. “Many mast cell diseases exhibit a sex bias in children and if we can identify the timing and the mechanism of what’s influencing the change, we’ll have an even better understanding of how these immune cells cause disease and know when to intervene with potentially new therapies.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

###

Newswise —

A computer interface that can decipher the thoughts of people who are unable to communicate could revolutionize the lives of those living with completely locked-in syndrome, according to a new paper publishing January 31st, 2017 in PLOS Biology. Counter to expectations, the participants in the study reported being “happy”, despite their extreme condition. The research was conducted by a multinational team, led by Professor Niels Birbaumer, at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland.

Patients suffering from complete paralysis, but with preserved awareness, cognition, and eye movements and blinking are classified as having locked-in syndrome. If eye movements are also lost, the condition is referred to as completely locked-in syndrome.

In the trial, patients with completely locked-in syndrome were able to respond “yes” or “no” to spoken questions, by thinking the answers. A non-invasive brain-computer interface detected their responses by measuring changes in blood oxygen levels in the brain.

The results overturn previous theories that postulate that people with completely locked-in syndrome lack the goal-directed thinking necessary to use a brain-computer interface and are, therefore, incapable of communication.

Extensive investigations were carried out in four patients with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) --a progressive motor neuron disease that leads to complete destruction of the part of the nervous system responsible for movement.

The researchers asked personal questions with known answers and open questions that needed “yes” or “no” answers including: “Your husband’s name is Joachim?” and “Are you happy?”. They found the questions elicited correct responses in seventy percent of the trials.

Professor Birbaumer said: “The striking results overturn my own theory that people with completely locked-in syndrome are not capable of communication. We found that all four patients we tested were able to answer the personal questions we asked them, using their thoughts alone. If we can replicate this study in more patients, I believe we could restore useful communication in completely locked-in states for people with motor neuron diseases.”

The question “Are you happy?” resulted in a consistent “yes” response from the four people, repeated over weeks of questioning.

Professor Birbaumer added: “We were initially surprised at the positive responses when we questioned the four completely locked-in patients about their quality of life. All four had accepted artificial ventilation in order to sustain their life, when breathing became impossible; thus, in a sense, they had already chosen to live. What we observed was that as long as they received satisfactory care at home, they found their quality of life acceptable. It is for this reason, if we could make this technique widely clinically available, it could have a huge impact on the day-to-day life of people with completely locked-in syndrome”.

In one case, a family requested that the researchers asked one of the participants whether he would agree for his daughter to marry her boyfriend ‘Mario’. The answer was “no”, nine times out of ten.

Professor John Donoghue, Director of the Wyss Center, said: “Restoring communication for completely locked-in patients is a crucial first step in the challenge to regain movement. The Wyss Center plans to build on the results of this study to develop clinically useful technology that will be available to people with paralysis resulting from ALS, stroke, or spinal cord injury. The technology used in the study also has broader applications that we believe could be further developed to treat and monitor people with a wide range of neuro-disorders.”

The brain-computer interface in the study used near-infrared spectroscopy combined with electroencephalography (EEG) to measure blood oxygenation and electrical activity in the brain. While other brain-computer interfaces have previously enabled some paralyzed patients to communicate, near-infrared spectroscopy is, so far, the only successful approach to restore communication to patients suffering from completely locked-in syndrome.

#####

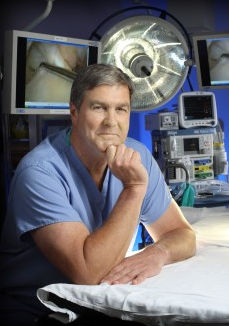

John Wilckens, M.D., is an associate professor of orthopaedic surgery at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. His areas of clinical expertise include baseball injuries, orthopaedic surgery and sports medicine. Dr. Wilckens serves as the medical director of Johns Hopkins Orthopaedics at White Marsh.

Dr. Wilckens holds research interests in sports medicine, adolescent sports injuries, ligament reconstruction, running injuries and arthroscopy.

Wilckens has served as the team physician to the Navy football team for 15 years and played for the Navy team himself during his time at the Naval Academy.

His mission is to keep players safe and playing football and he is currently investigating injuries in players after a recent rash of significant foot injuries occurred across the NCAA and the NFL.

Newswise —

A Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine researcher has received a $2.5 million grant from Gilead Sciences, a California-based biopharmaceutical company, to see if two so-far separately-used AIDS treatments are even more effective when used as a pair.

Lead researcher Michael M. Lederman, MD, Scott R. Inkley Professor of Medicine, and colleagues will combine interleukin-2, a protein made by the body that stimulates human killer-cells, with a lab-engineered monoclonal antibody that targets HIV.

“Administered alone, both Il-2 and certain monoclonal antibodies can reduce—but not necessarily eliminate— the presence of HIV in the body,” said Dr. Lederman. “Our study will go the next step and use them together. We want to see if they produce more of a wallop in tandem than when administered individually.”

Both IL-2 and monoclonal antibodies that neutralize HIV have been given safely to HIV-infected persons but not yet in combination. Study participants will be monitored for safety and tolerance by study staff members.

A key goal of the study is to determine if the new combined treatment can reduce latent HIV reservoirs, which consist of cells infected with HIV but not actively producing HIV. Reservoirs, which are difficult to measure, are present even in cases of treated HIV infection where there are no detectable levels of HIV in the blood. Although not active, the reservoirs are evidence that the infection is not cured since they can be reactivated by any of a number of reasons.

IL-2 is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating certain cancers. It activates killer cells and also activates HIV from latency (a positive development since the activated cells die when expressing virus). Monoclonal antibodies that neutralize HIV are cloned protein antibodies that bind to the surface of HIV and keep it from infecting the body’s immune cells. They also can help killer cells attack HIV infected cells that have been activated from latency to express virus.

In the 64-week study, patients in one treatment group will receive IL-2 and those in a second treatment group will receive IL-2 plus a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes HIV. The hope is that the size of the HIV reservoir will decrease in both groups and that the antibody will make the IL-2 treatment more potent. The study is set to include 16 patients and begin in the second half of 2017.

A previous retrospective study suggested that IL-2 treatment could decrease the size of latent HIV reservoirs. “We think it’s important to try to confirm those findings in a prospective trial and just as important, see if the addition of a monoclonal antibody enhances the activity of IL-2,” said Dr. Lederman.

He and his study colleagues are in discussions with the National Institutes of Health’s Vaccine Research Center to determine which monoclonal antibody to use among several the Center has developed to prevent or treat HIV infection.

Other CWRU School of Medicine researchers involved in the study are Jonathan Karn, PhD, Reinberger Professor of Molecular Biology; Benigno Rodriguez, MD, associate professor of medicine; and Rafick-Pierre Sekaly, PhD, professor of pathology.###

Newswise — LA JOLLA, CA –

Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have identified a brain hormone that appears to trigger fat burning in the gut. Their findings in animal models could have implications for future pharmaceutical development.

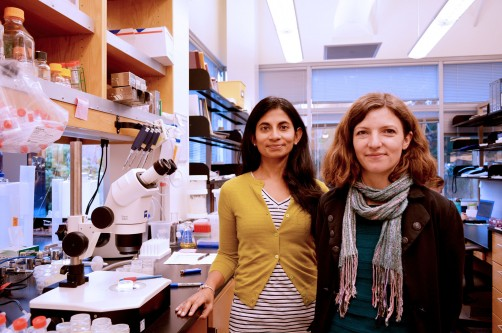

“This was basic science that unlocked an interesting mystery,” said TSRI Assistant Professor Supriya Srinivasan, senior author of the new study, published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Previous studies had shown that the neurotransmitter serotonin can drive fat loss. Yet no one was sure exactly how. To answer that question, Srinivasan and her colleagues experimented with roundworms called C. elegans, which are often used as model organisms in biology. These worms have simpler metabolic systems than humans, but their brains produce many of the same signaling molecules, leading many researchers to believe that findings in C. elegans may be relevant for humans.

The researchers deleted genes in C. elegans to see if they could interrupt the path between brain serotonin and fat burning. By testing one gene after another, they hoped to find the gene without which fat burning wouldn't occur. This process of elimination led them to a gene that codes for a neuropeptide hormone they named FLP-7 (pronounced “flip 7”).

Interestingly, they found that the mammalian version of FLP-7 (called Tachykinin) had been identified 80 years ago as a peptide that triggered muscle contractions when dribbled on pig intestines. Scientists back then believed this was a hormone that connected the brain to the gut, but no one had linked the neuropeptide to fat metabolism in the time since.

The next step in the new study was to determine if FLP-7 was directly linked to serotonin levels in the brain. Study first author Lavinia Palamiuc, a TSRI research associate, spearheaded this effort by tagging FLP-7 with a fluorescent red protein so that it could be visualized in living animals, possible because the roundworm body is transparent. Her work revealed that FLP-7 was indeed secreted from neurons in the brain in response to elevated serotonin levels. FLP-7 then traveled through the circulatory system to start the fat burning process in the gut.

“That was a big moment for us,” said Srinivasan. For the first time, researchers had found a brain hormone that specifically and selectively stimulates fat metabolism, without any effect on food intake.

Altogether, the newly discovered fat-burning pathway works like this: a neural circuit in the brain produces serotonin in response to sensory cues, such as food availability. This signals another set of neurons to begin producing FLP-7. FLP-7 then activates a receptor in intestinal cells, and the intestines begin turning fat into energy.

Next, the researchers investigated the consequences of manipulating FLP-7 levels. While increasing serotonin itself can have a broad impact on an animal’s food intake, movement and reproductive behavior, the researchers found that increasing FLP-7 levels farther downstream didn’t come with any obvious side effects. The worms continued to function normally while simply burning more fat.

Srinivasan said this finding could encourage future studies into how FLP-7 levels could be regulated without causing the side effects often experienced when manipulating overall serotonin levels.

In addition to Srinivasan and Palamiuc, authors of the study, “A tachykinin-like neuroendocrine signalling axis couples central serotonin action and nutrient sensing with peripheral lipid metabolism,” were Tallie Noble of Mira Costa College and Emily Witham, Harkaranveer Ratanpal and Megan Vaughan of TSRI.

Newswise —

Could inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer be prevented by changing the shape of a single protein?

There is an intimate link between uncontrolled inflammation in the gut associated with inflammatory bowel disease and the eventual development of colon cancer. This uncontrolled inflammation is associated with changes in bacteria populations in the gut, which can invade the mucosal tissue after damage to the protective cellular barrier lining the tissue.

But Virginia Tech researchers found that modifying the shape of IRAK-M, a protein that controls inflammation, can significantly reduce the clinical progression of both diseases in pre-clinical animal models.

The altered protein causes the immune system to become supercharged, clearing out the bacteria before they can do any damage. The team’s findings were published in eBioMedicine.

“When we tested mice with the altered IRAK-M protein, they had less inflammation overall, and remarkably less cancer,” said Coy Allen, an assistant professor of inflammatory disease in the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine and a Fralin Life Science Institute affiliate.

The next step, he said, will be to evaluate these findings in human patients through ongoing collaborations with Carilion Clinic and Duke University. The team is also evaluating their findings in laboratory-assembled ‘mini-guts’—live tissue models that Allen and his team assembled by growing intestinal stem cells on petri dishes to form highly complex small intestinal and colon tissue.

“Ultimately, if we can design therapeutics to target IRAK-M, we think it could be a viable strategy for preventing inflammatory bowel disease and cancer,” said Allen.

Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and the third most common cancer in men and women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

More than ten Virginia Tech faculty members and students are working on the project, including co-principal investigator Liwu Li, a professor of biological sciences in the College of Science; Clay Caswell, an assistant professor of bacteriology in the veterinary college; Rich Helm, an associate professor of biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences; Dan Slade, an assistant professor of biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences; and Tanya LeRoith, a clinical associate professor of anatomic pathology in the veterinary college.

Daniel Rothschild of Nevada City, California, currently in the combined Ph.D./D.V.M program in the veterinary college, is working in Allen’s lab, and was first author on the paper.

“Working on this project alongside Dr. Allen and our fellow collaborators has personally been a great experience,” said Rothschild. “It’s really exciting when your findings have the potential for clinical implications that can be applied to help patients. From a scientist’s perspective, that’s what it’s all about, and hopefully our findings provide a good avenue for development of future therapeutics to treat maladies such as inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer.”

Newswise —

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can develop after a traumatic event or events. Although it is most often associated with military personnel exposed to the trauma of combat, it can also disproportionately affect vulnerable American Indian and Alaskan-Native (AI/AN) populations. Because alcohol use disorders (AUDs) also have a disproportionate impact on AI/ANs, this study compared both lifetime PTSD and past-year AUD among AI/ANs and non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs).

Researchers analyzed data from the 2012-2013 U.S. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III, the fourth national survey conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The researchers estimated the odds of AUD among adults with and without PTSD by race. Of the 19,705 participants, 511 (301 women, 210 men) were AI/AN and 19,194 (10,639 women, 8,555 men) were NHW.

The investigators found that both PTSD and AUD were more common among AI/ANs than NHWs. Although PTSD was significantly associated with AUD in both populations, the association was significantly more prevalent among AI/ANs. Thus, among men the rate of both PTSD and AUD in AI/ANs was more than three times that of NHW men (9.5% vs. 3.1%). The authors suggested that screening and interventions for PTSD in tribal-government programs and in AI/AN health services could help to reduce the greater risk for AUD in AI/ANs. They also called for studies that measure trauma resulting from cultural losses and their chronic effects, as well as childhood and adolescent traumas that are specific to AI/ANs.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY