News

Newswise —

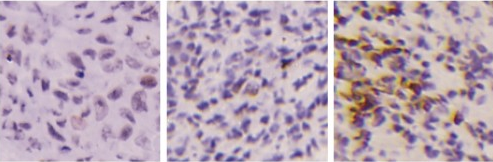

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have discovered that the metabolic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (PGAM1) helps cancer cells repair their DNA and found that inhibiting PGAM1 sensitizes tumors to the cancer drug Olaparib (Lynparza). Their findings in the study “Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 regulates dNTP pool and promotes homologous recombination repair in cancer cells,” which has been published in The Journal of Cell Biology, suggest that this FDA-approved ovarian cancer medicine has the potential to treat a wider range of cancer types than currently indicated.

Cancer cells often alter their metabolic pathways in order to synthesize the materials they need for rapid growth. By producing the metabolite 2-phosphoglycerate, PGAM1 regulates several different metabolic pathways, and the levels of this enzyme are abnormally elevated in various human cancers, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer.

Min Huang, Jian Ding, and colleagues at the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences, discovered that inhibiting PGAM1 made cancer cells more sensitive to drugs that induce breaks in both strands of the cells’ DNA. This was because the cells were unable to activate a pathway called homologous recombination that repairs this type of DNA damage. The researchers found that cells synthesized fewer deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs)—the building blocks of DNA—when PGAM1 was inhibited. This, in turn, activated a cellular stress response pathway that culminated in the degradation of a protein called CtIP that is required for homologous recombination repair.

Cancers carrying mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes are unable to undergo homologous recombination and therefore rely on a different pathway to repair their DNA and continue growing. Olaparib blocks this second repair pathway by inhibiting an enzyme called poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP). Olaparib was approved by the FDA in 2014 to treat ovarian cancers with BRCA mutations.

In this study, the researchers tested the effects of Olaparib on the tumors formed by human breast cancer cells injected into mice. Olaparib had no effect on tumors formed by breast cancer cells containing functional BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. But by combining the drug with a PGAM1 inhibitor to impair both homologous recombination and PARP-dependent DNA repair, the researchers were able to significantly suppress tumor growth.“This suggests that PGAM1 inhibitors can sensitize cancers to PARP inhibitors such as Olaparib, thereby expanding the benefits of PARP inhibitors to BRCA1/2-proficient cancers, particularly triple-negative breast cancers that currently lack effective therapies,” says author Min Huang.

Qu et al., 2017. J. Cell Biol. http://jcb.rupress.org/cgi/doi/10.1083/jcb.201607008?PR

# # #

Newswise —

Believe it or not, winter has officially begun! And, although there has been a lack of significant snowfall and cold temperatures in our area, we should still be prepared for the possibility of more seasonable weather.

Typical winters in the Northeast are beautiful, especially after a fresh snowfall. However, as many of us know, the arrival of snow means that it is time to dust off our shovels and get to digging! “We understand that shoveling snow is our winter norm, but did you know that shoveling snow can actually pose a serious cardiac health risk to some of us?” asks George Becker, M.D., Director, Emergency Department, The Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, NJ.

In fact, although most people are not in danger from shoveling, the American Heart Association (AHA) still shares useful tips for anyone shoveling snow in the winter. To begin with, the AHA recommends that those who don’t exercise on a regular basis, those that have a medical condition, or those that are middle age or older consult with a doctor before shoveling.

The AHA also has the following general tips for staying safe while shoveling:

• Take frequent rest breaks during shoveling.• Don’t eat a heavy meal prior or soon after shoveling.• Use a small shovel or consider a snow thrower.• Don’t drink alcoholic beverages before or immediately after shoveling.• Be aware of the dangers of hypothermia. • Learn the heart attack warning signs and listen to your body.Some signs that you might be having a heart attack are pain in the chest, arm(s), back, neck, jaw or stomach. You might also break out in a cold sweat, feel short of breath, nauseated, lightheaded, or uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness in the center of your chest.

Adds Dr. Becker, “If you are concerned that you may be having a heart attack, you should not hesitate about seeking medical treatment—every minute is crucial when experiencing a heart attack. Call 911 immediately or head directly to the closest emergency room.”

Shoveling Snow: Winter Chore or Health Hazard?

Believe it or not, winter has officially begun! And, although there has been a lack of significant snowfall and cold temperatures in our area, we should still be prepared for the possibility of more seasonable weather.

Typical winters in the Northeast are beautiful, especially after a fresh snowfall. However, as many of us know, the arrival of snow means that it is time to dust off our shovels and get to digging! “We understand that shoveling snow is our winter norm, but did you know that shoveling snow can actually pose a serious cardiac health risk to some of us?” asks George Becker, M.D., Director, Emergency Department, The Valley Hospital.

In fact, although most people are not in danger from shoveling, the American Heart Association (AHA) still shares useful tips for anyone shoveling snow in the winter. To begin with, the AHA recommends that those who don’t exercise on a regular basis, those that have a medical condition, or those that are middle age or older consult with a doctor before shoveling.

The AHA also has the following general tips for staying safe while shoveling:

• Take frequent rest breaks during shoveling.• Don’t eat a heavy meal prior or soon after shoveling.• Use a small shovel or consider a snow thrower.• Don’t drink alcoholic beverages before or immediately after shoveling.• Be aware of the dangers of hypothermia. • Learn the heart attack warning signs and listen to your body.Some signs that you might be having a heart attack are pain in the chest, arm(s), back, neck, jaw or stomach. You might also break out in a cold sweat, feel short of breath, nauseated, lightheaded, or uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness in the center of your chest.

Adds Dr. Becker, “If you are concerned that you may be having a heart attack, you should not hesitate about seeking medical treatment—every minute is crucial when experiencing a heart attack. Call 911 immediately or head directly to the closest emergency room.”

Our Emergency Department, located at 223 N. Van Dien Avenue in Ridgewood, NJ is open 24/7, 365 days a year and is staffed with physicians who are board certified in emergency medicine.

Newswise — TORONTO, Canada –

In a bold and very challenging move, thoracic surgeons at Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network removed severely infected lungs from a dying mom, keeping her alive without lungs for six days, so that she could recover enough to receive a life-saving lung transplant.

This is believed to be the first such procedure in the world, made possible by advanced life support technology, a dedicated and diverse surgical, respirology, intensive care and perfusion team, as well as the grit and gumption of the patient and her close-knit family.

“This was bold and very challenging, but Melissa was dying before our eyes,” recalls Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, Surgeon-in-Chief, Sprott Department of Surgery at University Health Network (UHN), one of three thoracic surgeons who operated together on Melissa to remove both her lungs. “We had to make a decision because Melissa was going to die that night. Melissa gave us the courage to go ahead.”

Melissa Benoit, then 32, was brought into Toronto General Hospital’s (TGH) Medical Surgical Intensive Care Unit (MSICU) in early April 2016, sedated and on a ventilator to help her laboured breathing. For the past three years, Melissa, who has cystic fibrosis, had been prescribed antibiotics to fight off increasingly frequent chest infections.

A recent bout of influenza just before her hospital admission had left Melissa gasping for air, with coughing fits so harsh that she fractured her ribs. Her inflamed lungs began to fill with blood, pus and mucous, decreasing the amount of air entering her lungs, similar to a person drowning.

As Dr. Niall Ferguson, Head of Critical Care Medicine at the University Health Network (UHN) and Mount Sinai, describes it, the influenza “tipped her over the edge into respiratory failure. She got into a spiral from which her lungs were not going to recover. Her only hope of recovery was a lung transplant.”

Melissa’s oxygen levels dipped so low, conventional ventilation was no longer enough. To help her breathe, and to gain more time until donor lungs became available, physicians placed her on Extra-Corporeal Lung Support (ECLS), a temporary life-support medical device that supports the work of the lungs and heart. Despite this, Melissa’s condition worsened.

The bacteria in her lungs developed resistance to most antibiotics, and spread throughout her body. Her blood pressure dropped. She slid into septic shock, triggering inflammation, leaky blood vessels and reduced blood flow. One by one, her organs began to shut down. She had to have kidney dialysis.

Melissa was now on maximum doses of three medications to maintain her blood pressure, along with the most advanced respiratory support, and on last-line powerful antibiotics, the last option for patients resistant to other available antibiotics. The team was still waiting for donor lungs but, by this time, Melissa was too sick to have a lung transplant.

Dr. Marcelo Cypel, the thoracic surgeon on call that late April weekend, kept a careful watch on Melissa. On a Sunday afternoon, with the clock ticking, he kept weighing her risk of death versus the risk of trying something which had never been done before.

It was bold, but scientifically sound. Removing both her lungs - the source of bacterial infection – could save her life.

Dr. Cypel gathered his colleagues, calling in Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, Dr. Tom Waddell, Head of Thoracic Surgery at UHN, Dr. Niall Ferguson, and respirologist Dr. Mathew Binnie – all seasoned and well-known for their skills in navigating complex cases, along with Melissa’s husband, mom and dad.

The surgical team had been discussing the concept of this procedure for several years. They had observed patients with cystic fibrosis, waiting for a lung transplant, who developed severe lung infections. These infections spread through the bloodstream into their bodies, resulting in septic shock and death, despite maximum support on the ECLS device.

While the team faced many unknowns – risk of bleeding into an empty chest cavity, whether her blood pressure and oxygen levels could be supported afterwards, and if she would even survive the operation – they agreed that Melissa was a possible candidate, and that it was her only chance, although a slim one.

As Dr. Keshavjee explained, she likely still had enough strength to withstand the procedure and get better afterwards, the source of the infection was clear-cut and difficult to control in current circumstances, the family understood the risks and explained that Melissa had often told them she would want to try everything possible to live for her husband Christopher and two-year-old daughter, Olivia.

“Things were so bad for so long, we needed something to go right,” remembers, Chris, “and this new procedure was the first piece of good news in a long time. We needed this chance.”

As Melissa tells it, Chris was the one who “held my life in his hands...He had to trust in himself, knowing me, relying on past conversations, and he chose exactly what I would have told him to.”

Melissa’s mom, Sue, was so eager to save her daughter’s life, she urged the team to go ahead: “Melissa always volunteers for any study or clinical trial. She would want to do this. Let’s not waste any more time and get her into the OR.”

At 9:00 pm that Sunday evening in mid-April, a team of 13 operating room staff, including three thoracic surgeons – Drs. Cypel, Keshavjee and Waddell - removed Melissa’s lungs, one at a time, in a nine-hour procedure. Her lungs had become so engorged with mucous and pus that they were as hard as footballs, recalls Dr. Keshavjee. “Technically, it was difficult to get them out of her chest.” But within hours of removing her lungs, Melissa improved dramatically. She did not need blood pressure medication, and most of her organs began to improve.

To keep Melissa alive, she was placed on the most sophisticated support possible for her heart and lungs. Two external life support circuits were connected to her heart via tubes placed through her chest.

A Novalung device, a small portable artificial lung, was connected by arteries and veins to her heart to function as the missing lungs. Working with the pumping heart, the device added oxygen to her blood, removed carbon dioxide, while helping to maintain continuous blood flow. At the same time, another external device, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which has an external pump, circuit and oxygenator for the gas exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, also helped to circulate oxygen-rich blood throughout her body.

TGH is a leader in using these technologies, with the largest such program in Canada, performing up to 100 ECLS cases per year. ECLS specialists or perfusionists and MSICU nurses are specially trained in caring for patients on various ECLS devices. Six days later, a pair of donor lungs became available and Melissa was stable enough to receive a lung transplant in late April 2016.

“The transplant procedure was not complicated because half of it was done already,” noted Dr. Cypel, “Her new lungs functioned beautifully and inflated easily. Perfect.” For the past several months, Melissa has been steadily improving. Her previously thick hair is growing back, she can play with her daughter for whole days without getting tired, and she has not needed a walker or cane for the past month. She is still on kidney dialysis.

“It’s the simple things I missed the most,” she said, “I want to be there for Chris and Olivia, even through her temper tantrums! I want to hear Olivia’s voice, play with her and read her stories.”

The medical team is developing criteria for the select types of patients who could be candidates for this novel procedure while waiting for a lung transplantation. The report of this case by Drs. Marcelo Cypel, Shaf Keshavjee, Tom Waddell, Lianne Singer, Lorenzo del Sorbo, Eddy Fan, Mathew Binnie and Niall Ferguson on Melissa Benoit entitled, “Bilateral pneumonectomy to treat uncontrolled sepsis in a patient awaiting lung transplantation” is published online in The Journal of Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, November, 2016.

Newswise —

Adding further to its expanding scope of pediatric and neurological services, NYU Lutheran Medical Center is now making it easier for families to identify and treat neurological and psychological issues that could impair childhood development.

The development of the brain in childhood has life-long effects on overall health and well-being, including cognition, learning ability, behavior, and social skills. When an injury involving the brain or the possibility of a developmental delay is presented early in life, it needs to be identified and treated to prevent future problems into adulthood.

Gianna Locascio, PsyD, NYU Lutheran’s new pediatric neuropsychologist, has devoted her career to helping families identify these conditions and develop appropriate treatment plans for a healthy future.

“When I evaluate a child, I create a neurocognitive profile to identify strengths and weaknesses in all areas of cognitive function,” says Locascio. Specifically, she looks at intellect, attention, concentration, memory, motor coordination, personality, language skills, and other factors. Planning, organizing, and shifting attention from one task to another efficiently also are key areas she assesses.

Once an evaluation is completed, Locascio often refers patients to an appropriate, conveniently located therapist or specialist within the NYU Langone health system, and continues to monitor the child’s progress through development. Over time, she may update her comprehensive recommendations to maximize the child’s functioning at home and in social, community, and academic settings.

“The key to providing comprehensive care is to ensure that the patient is healthy and thriving in a range of areas,” says Steven L. Galetta, MD, the Philip K. Moskowitz, MD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Neurology at NYU Langone Medical Center. “Monitoring progress and adjusting care recommendations based on lifestyle changes is important in all medical practices, but particularly neurological care. Dr. Locascio is a valuable addition to NYU Langone health system’s neuropsychological testing services and will play an important role in the comprehensive approach at NYU Lutheran.”

Locascio specializes in cognitive issues related to traumatic brain injury, concussion, stroke, epilepsy, brain tumors, encephalitis, cerebral palsy, sickle cell disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, Down syndrome, autism spectrum, spina bifida, Sturge-Weber syndrome, and other childhood and adolescent disorders.

Her passion for pediatric neuropsychology is rooted in her love of science and desire to help young people develop into healthy adults. “It’s very rewarding to work with children and adolescents,” she says. “There are so many ways to help maximize function. I have seen patients go on to extraordinary progress.”

Locascio is the only pediatric neuropsychologist in Brooklyn board certified in both clinical neuropsychology and pediatric neuropsychology. An undergraduate alumna of Lafayette College, she earned her master’s degree and doctorate from Rutgers University with dual concentration in school psychology and neuropsychology. She completed a fellowship in neuropsychology at Kennedy Krieger Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

To make an appointment with Gianna Locascio, PsyD, or for more information please call 718.630.7316.

Newswise — New York and Boston —

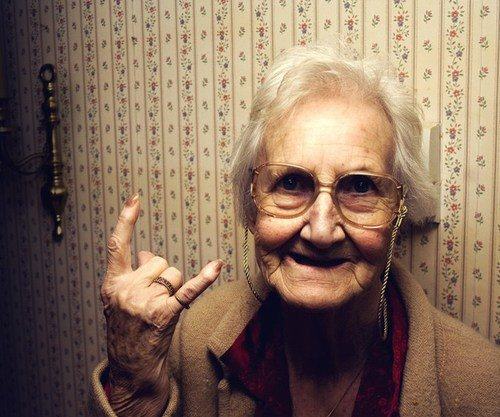

Improving dietary resilience and better integration of nutrition in the health care system can promote healthy aging and may significantly reduce the financial and societal burden of the “silver tsunami.” This is the key finding of a “Nutritional Considerations for Healthy Aging and Reduction in Age-Related Chronic Disease,” a new paper initiated under the auspices of the Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science Working Group on Nutrition for Aging Population, and published in Advances in Nutrition.

By 2050, the number of persons aged 80 years old and over will reach 392 million, about three times the 2013 population. According to the report, an increasingly large portion of the population will be vulnerable to nutritional frailty, a state commonly seen in older adults, characterized by sudden significant weight-loss and loss of muscle mass and strength, or an essential loss of physiologic reserves, making the person susceptible to disability. Ironically, while increasing numbers of older adults are obese, many are also susceptible to nutritional frailty and, as a result, age-related diseases including sarcopenia, cognitive decline, and infectious disease.

The review concludes that exploring dietary resilience, defined as a conceptual model to describe material, physical, psychological and social factors that influence food purchase, preparation and consumption, is needed to better understand older adults’ access to meal quality and mealtime experience. A recent model to frame food intake includes the addition of more randomized clinical trials that include older adults with disease and medication. This will help to identify their specific nutrient needs, biomarkers to understand the impact of advancing age on protein requirements, skeletal muscle turnover and a re-evaluation of how BMI guidelines are used.

“A nutritional assessment model that takes into consideration the effect of aging on muscle mass, weight loss and nutrient absorption is crucial to overall wellness in our elderly population,” said Gilles Bergeron, Ph.D., executive director, The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science at the New York Academy of Sciences, New York, NY. “However, nutrition recommendations are usually based on that of a typical healthy adult, and fail to consider the effect of aging on muscle mass, weight loss, and nutrient absorption and utilization.”

Simin Nikbin Meydani, D.V.M., Ph.D., director of the Nutritional Immunology Laboratory at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston, MA concurs. “Much greater emphasis needs to be placed on prioritizing research that will fill the knowledge gaps and provide the kind of data needed by health and nutrition experts if we’re going to address this problem,” she said. “There also needs to be more education about on-going nutritional needs for those involved with elder-care – not only in a clinical setting, but also for family members who are responsible for aging adults.”

Additional authors of this review are Julie Shlisky, Ph.D., consultant at The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science; David E. Bloom, Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston; Amy R. Beaudreault, World Food Center, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA; Katherine L. Tucker, Department of Clinical Laboratory and Nutritional Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA; Heather H Keller, Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging, Applied Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Yvonne Freund-Levi, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society (NVS), Division of Clinical Geriatrics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, Department of Geriatrics, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden and Department of Psychiatry, Tiohundra Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; Roger A Fielding, Nutrition, Exercise Physiology and Sarcopenia Laboratory at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts; Feon W. Cheng, University of Vermont College of Medicine, Burlington, VT; and Gordon L. Jensen, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA; and Dayong Wu, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA. Please see the review for conflicts of interest.

Shlisky, J., Bloom, D. E., Beaudreault, A. R., Tucker, K. L., Keller, H. H., Freund-Levi, Y., Fielding, R. A., Cheng, F. W., Jensen, G. L., Wu, D., Meydani, S. M.. (2017, January); 8:17-26. Nutritional considerations for healthy aging and reduction in age-related chronic disease. Advances in Nutrition. doi:10.3945/an.116.013474.

# # #

Newswise — AMES, Iowa –

If your New Year’s resolution was to exercise more in 2017, chances are you’ve already given up or you’re on the verge of doing so. To reach your goal, you may want to consider joining a gym, based on the results of a new study from a team of Iowa State University researchers.

Duck-chul (DC) Lee, an assistant professor of kinesiology and corresponding author of the paper, says the study found people who belonged to a health club not only exercised more – for both aerobic activity and strength training – they also had better cardiovascular health outcomes. Those health benefits were even greater for people who had a gym membership for more than a year, Lee said. The research is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“It’s not surprising that people with a gym membership work out more, but the difference in our results is pretty dramatic,” Lee said. “Gym members were 14 times more aerobically active than non-members and 10 times more likely to meet muscle-strengthening guidelines, regardless of their age and weight.” The results were similar in both men and women.

It’s recommended that adults get 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity each week, such as brisk walking or running. The Physical Activity Guidelines also suggest two days of weight lifting or other muscle-strengthening activities. Despite strong evidence of the health benefits, only half of Americans are getting enough aerobic activity and about 20 percent meet the guidelines for strength training.

Iowa State researchers found 75 percent of study participants with gym memberships, compared to 18 percent of non-members, met the guidelines for both types of activity. In fact, the majority of those who went to a health club exceeded standards and spent 300 minutes or more running, biking or doing some type of cardio workout each week. That adds up to nearly six hours of additional activity, compared to non-members.

Gym members overall had a more active lifestyle. Researchers say members were just as active outside the gym and in their daily lives, which combined contributed to better health outcomes. Here are a few of the results for members:

• Lower odds of being obese – weight loss is a main reason for joining a gym• Smaller waist circumference – about 1.5 inches less for men and a similar trend for women• Lower resting heart rate – about five beats lower than non-members• Higher cardiorespiratory fitness – this measures heart strength, lung function, blood circulation and muscle mass

Elizabeth Schroeder, lead author and a former Iowa State graduate student, says while most people join a gym to lose weight, the research shows the many benefits of exercise.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for individuals in the U.S. As our paper shows, a health club membership is associated with more favorable cardiovascular health,” Schroeder said. “I hope the results help people be more active, potentially at a health club where they can easily perform resistance exercise, and see that exercise may help prevent cardiovascular disease.”

This is also one of the first studies to measure weight lifting and resistance exercise. Lee says this type of activity is beneficial because it builds muscle mass, which burns more energy and lowers the risk of obesity and the risk of sarcopenia for older adults.

Researchers did not ask participants if they spend time at the gym running on a treadmill, riding a bike, attending a group fitness class or other activity. However, Warren Franke, a co-author and professor of kinesiology, says health clubs offer a variety of options and benefits for people who are new to exercise. Franke is director of Iowa State’s Exercise Clinic.

“By joining a quality fitness facility, a new exerciser will be around like-minded people and have access to professionals who can help them be successful,” Franke said. “Access to quality exercise equipment, social support and even the financial commitment may help spur someone to continue exercising. Not all facilities are the same, so it’s important to find the ‘right’ fit.”

Incentivizing workouts

Most people spend much of their day sitting at a desk, and do little heavy lifting to create resistance against their muscles. Increasing activity levels lowers the risk for diseases such as Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, Lee said. However, only 18 percent of Americans have a gym membership. Based on the research results, incentives to boost membership could be beneficial, Lee said.

Several companies have on-site workout facilities for employees or provide some form of reward for going to the gym. Greg Welk, a co-author and professor of kinesiology, says efforts to increase these opportunities not only improves employee health, but also reduce sick days and lower insurance costs. As a coordinator of the ISU’s Wellness Works, Welk provides companies with the tools and support to implement effective wellness programming.

“Access to fitness facilities can provide employees with an incentive to take responsibility and adopt regular habits of physical activity,” Welk said. “A fitness center can promote improved fitness, but employees may also need support for eating habits, managing stress and other health needs.”

Researchers say it’s important to note that some data for the study were collected while people were at the gym, which would exclude people who have a membership, but are not using it. It is also a cross-sectional study, so researchers cannot directly state a cause and effect.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

STEROID ORIGINALLY DISCOVERED IN THE DOGFISH SHARK ATTACKS PARKINSON’S-RELATED TOXIN IN ANIMAL MODEL

Newswise — WASHINGTON —

A synthesized steroid mirroring one naturally made by the dogfish shark prevents the buildup of a lethal protein implicated in some neurodegenerative diseases, reports an international research team studying an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. The clustering of this protein, alpha-synuclein (α-synuclein), is the hallmark of Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies, suggesting a new potential compound for therapeutic research.

The finding, published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also demonstrated that the synthesized steroid, called squalamine, reduced the toxicity of α-synuclein clumps that already existed.

The pre-clinical study results show that squalamine prevents and eliminates α-synuclein build up inside neurons by unsticking the protein from the inner wall of nerve cells, where it clings and builds up into toxic clumps, researchers say.

The animal model used for this study, C. elegans, is a nematode worm genetically engineered to produce human α-synuclein in its muscles. As these worms age, α-synuclein builds up within their muscle cells causing cell damage and paralysis.

“We could literally see that squalamine, given orally to the worms, did not allow α-synuclein to cluster, and prevented muscular paralysis inside the worms,” says the study’s co-senior author, Michael Zasloff, MD, PhD, professor of surgery and pediatrics at Georgetown University School of Medicine and scientific director of the MedStar Georgetown Transplant Institute.The study’s lead author, graduate student Michele Perni, and other co-senior authors, Michele Vendruscolo, PhD and Christopher M. Dobson, DPhil, ScD, are from Cambridge University. An additional co-senior author, Adriaan Bax, PhD, is from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. Scientists from the Netherlands, Italy and Spain also contributed to this research.

Zasloff, an expert in innate immune systems, has been studying squalamine for more than 20 years. He discovered it in dogfish sharks in 1993 and synthesized it in 1995 (in a process that does not involve use of any natural shark tissue). His research, as well as that by other scientists, has established antiviral and anticancer properties of the compound. This is the first study to show it has neurological benefits in in vivo models of Parkinson’s.

In Parkinson’s disease, α-synuclein, a normal protein present within the nervous system, forms toxic clumps that damage and ultimately destroy the neurons in which they form. Considerable research has been directed at discovering compounds that prevent the formation of these masses, thereby representing potential therapeutics for Parkinson’s disease.

In this study, the researchers demonstrated in a series of in vitro experiments that squalamine, a positively charged molecule with a high affinity for negatively charged membranes, could literally “kick off” α-synuclein from negatively charged membranes, where the protein binds, preventing the formation of the toxic clumps. The research team also showed that squalamine could protect healthy human neuronal cells from being damaged by exposure to pre-formed toxic masses of α-synuclein, by preventing them from adhering to the outer membrane of the neuronal cells.

The researchers then extended these studies to a living system, C. elegans, a well-studied model of Parkinson’s disease. “Orally administered squalamine prevented the formation of toxic α-synuclein clumps in this complex animal, and rescued the animal from loss of mobility,” Zasloff explains. “This experiment taught us that the basic mechanism demonstrated in vitro achieved the anticipated outcome in an animal.”

The study's co-senior author, Professor Christopher Dobson, DPhil, Master of St John's College, University of Cambridge says, "Squalamine gives us a first generation compound, which we believe that we can incrementally improve through further studies of the underlying mechanism by which it affects the aggregation of alpha-synuclein."

Zasloff says a clinical trial with squalamine in Parkinson’s disease is being planned. “Squalamine could be especially suited to work in the gut with the goal of treating the gastrointestinal symptoms of Parkinson’s,” he adds.

Zasloff is the inventor on a patent application that has been filed related to the technology described in this paper. The other authors report having no personal financial interests related to the study.

Additional authors include Celine Galvagnion, Georg Meisl, Martin B. D. Müller, Pavan K. Challa, Patrick Flagmeier, Samuel I. A. Cohen, Pietro Sormanni, Gabriella T. Heller, Francesco A. Aprile, Tuomas P. J. Knowles, Michele Vendruscolo, Serene W. Chen, Ryan Limbocker and Julius Kirkegaard from the University of Cambridge, England; Alexander S. Maltsev, from NIDDK; Ellen A. Nollen, from the European Research Institute for the Biology of Aging, Groningen, The Netherlands; Roberta Cascella, Cristina Cecchi, and Fabrizio Chiti, from the University of Florence; and Nunilo Cremades, from the University of Zaragoza, Spain.

The study was funded by the NIH Intramural Research Program, the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, the European Research Council (ERC), and the Centre for Misfolding Diseases at Cambridge.

About Georgetown University Medical CenterGeorgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC’s mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization, which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health. Connect with GUMC on Facebook (Facebook.com/GUMCUpdate), Twitter (@gumedcenter) and Instagram (@gumedcenter).

Newswise —

Many infectious diseases are one and done; people get sick once and then they are protected from another bout of the same illness. For some of these infections – chickenpox, for example – a small number of microbes persist in the body long after the symptoms have gone away. Often, such microbes can reactivate when the person’s immunity has waned with age or illness, and cause disease again.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis studying leishmaniasis, a tropical disease that kills tens of thousands of people every year, believe they have found an explanation for the seemingly paradoxical connection between long-term infection and long-term immunity. By constantly reminding the immune system what the parasite that causes leishmaniasis looks like, a persistent infection keeps the immune system on alert against new encounters, even while it carries the risk of causing disease later in life, the researchers found.

Understanding how persistent infection leads to long-term immunity could help researchers design vaccines and treatments for persistent pathogens.

The research is published the week of Jan. 16 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“People had been thinking of the role of the immune system in persistent infection in terms of mowing down any pathogens that reactivate in order to protect the body from disease,” said Stephen Beverley, PhD, the Marvin A. Brennecke Professor of Molecular Microbiology and the study’s senior author. “What was often overlooked was that in the process of doing this, the immune system is constantly being stimulated, which potentially promotes protection against future illness.”

In a persistent infection, a small population of microbes remains in the body long after the patient’s symptoms are gone. In addition to the parasite that causes leishmaniasis, many kinds of microbes can cause persistent infections, including bacteria responsible for tuberculosis and viruses that lead to herpes and chickenpox.

“A lot of pathogens cause persistent infections, but the process was something of a black box,” said Michael Mandell, PhD, the first author on the study. Mandell, who conducted the research for the study as a graduate student, is now an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico. “Nobody really knew what was going on during persistent infection and why it was associated with immunity.”

To find out, Mandell and Beverley studied Leishmania, a group of parasites that cause ulcers on the skin and can infect internal organs. An estimated 250 million people worldwide are infected with the parasite – found in tropical areas – and 12 million have active disease. The disease can be disfiguring or even fatal, but once a person is infected, he or she is protected from getting sick a second time. In other words, infection confers long-term immunity.

People are thought to continue to harbor the parasite at low numbers for years after they recover from the disease, including some people treated with anti-leishmania drugs. This persistence may be to the benefit of their human hosts; studies in mice have shown that completely clearing the parasite often makes the animals susceptible to another bout of disease if they encounter the parasite again.

Studying mice, the researchers used fluorescent markers to distinguish different types of mouse cells, and found that most of the parasites live in immune cells capable of killing the parasites. Yet, despite their dangerous homes, the parasites appeared normal in shape and size.

Further, most of the parasites continued to multiply, yet the total number of parasites stayed the same over time.

“Mike Mandell called it the ‘Jimmy Hoffa effect’ because we couldn’t locate the body,” Beverley said. “We were unable to show directly that the parasites were being killed. But some of them must have been dying because the numbers weren’t going up.”

The immune cells that housed the parasites are responsible for killing pathogens and activating a more robust immune response. It is this process – the ongoing multiplication and killing of parasites – that the researchers believe underlies the long-term immunity associated with persistent infection, and thus explains why people typically can’t get sick with the same pathogen twice.

“It seems that our immunologic memory needs reminding sometimes,” Mandell said. “As the persistent parasites replicate and get killed, they are continually stimulating the immune system, keeping it primed and ready for any new encounters with the parasite.”

These findings suggest that there are benefits as well as dangers to persistent infection, and, for some organisms at least, developing a vaccine that elicits life-long immunity might require a live vaccine that has the ability to persist without sickening people.

“Usually scientists design vaccines to get sterilizing immunity. They’re trying to just kill all the bugs,” Beverley said. “But what you really need is protection against the pathologic consequences of the disease, not necessarily sterilizing immunity. For some of these organisms, solid, long-term protection may come at the price of persistent infection.”

Newswise —

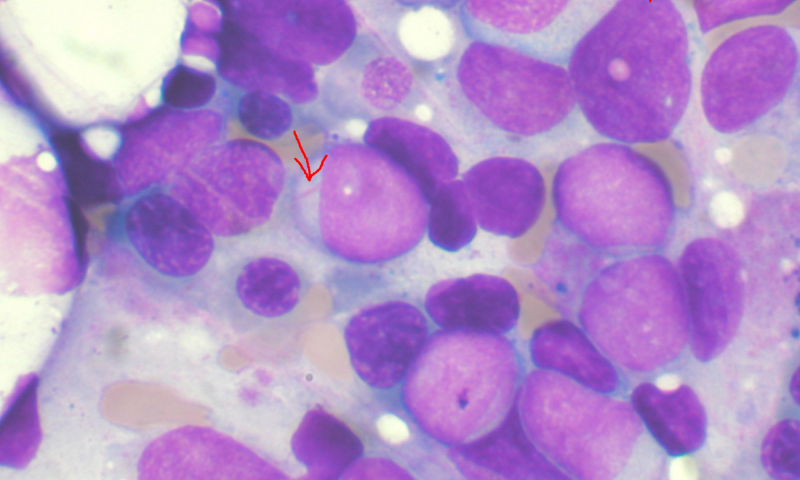

An international collaboration led by clinical researchers at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute has shown proof-of-concept that truly personalised therapy will be possible in the future for people with cancer. Details of how a knowledge bank could be used to find the best treatment option for people with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) are published today in Nature Genetics.

AML is an aggressive blood cancer that develops in bone marrow cells. Earlier this year, the team reported there are 11 types of AML, each with distinct genetic features. Now they report how a patient's individual genetic details can be incorporated into predicting the outcome and treatment choice for that patient.

They built a knowledge bank using data from 1,540 patients with AML who participated in clinical trials in Germany and Austria, combining information on genetic features, treatment schedule and outcome for each person. From this, the team developed a tool that shows how the experience captured in the knowledge bank could be used to provide personalised information about the best treatment options for a new patient.

There are two major treatment options for young patients with AML - a stem cell transplant or chemotherapy. Stem cell transplants cure more patients overall but up to one in four people die from complications of the transplant and a further one in four experience long-term side effects. Weighing up the benefits of better cure rates with transplant against the risks of worse early mortality is a harrowing decision for patients and their clinicians. The team showed that these benefits and risks could be accurately calculated for an individual patient, enabling therapeutic choices to become personalised.

The team estimates that up to one in three patients would be prescribed a different treatment regimen using the tool compared with current practice. In the long term they hope the tool could spare one in ten young AML patients from a transplant while maintaining overall survival rates.

Senior author Dr Peter Campbell of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute said: "The knowledge bank approach makes far more detailed and accurate predictions about the likely future course of a patient with AML than what we can make in the clinic at the moment. Current guides use a simple set of rules based on only a few genetic findings. For any given patient, using the new tool we can compare the likely future outcomes under a transplant route versus a standard chemotherapy route - this means that we can make a treatment choice that is personally tailored to the unique features of that particular patient."

The tool is currently available for scientists to use in research but needs further testing before it can be used to prescribe treatments in AML clinics.

Lead author Dr Moritz Gerstung of the European Bioinformatics Institute said: "It has long been recognised that cancer is a complex genetic disease. Our study provides an example of how detailed genetic and clinical information can be rationally incorporated into clinical decisions for individual patients. We tested this philosophy in one type of leukaemia, but the concept could theoretically be applied in other cancers with difficult clinical decisions as well. Our analysis reveals that knowledge banks of up to 10,000 patients would be needed to obtain the precision needed for routine clinical application."

Using large scale genetic studies as a source to predict the best treatment option for future patients is an idea that Genomics England is trying to build alongside similar programmes around the world, such as the National Institutes of Health Precision Medicine Initiative in the US.

The authors believe this paper is a step towards validation of genetic techniques as a route to personalised medicine.

Co-senior author Dr Hartmut Döhner of University of Ulm said: "Building knowledge banks is not easy. To get accurate treatment predictions you need data from thousands of patients and all tumour types. Furthermore, such knowledge banks will need continuous updating as new therapies become approved and available. As genetic testing enters routine clinical practice, there is an opportunity to learn from patients undergoing care in our health systems. Our paper gives the first real evidence that the approach is worthwhile, how it could be used and what the scale needs to be."

###

Newswise — New Brunswick, N.J. -

Cervical cancer is almost always caused by the high-risk types of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which nearly every sexually active person will be exposed to in their lifetime. People with healthy immune systems are able to clear the virus, but when the high risk strains “hijack” or infect specific cells of the cervix it can lead to abnormal cell growth and precancerous changes. Over time and with persistent infection, this leads to cervical cancer. HPV infection can also lead to penile, anal and throat and mouth cancers. Unfortunately, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), incidence rates of HPV-associated cancers have continued to rise, with approximately 39,000 new HPV-associated cancers diagnosed each year in the United States. People who smoke or have lowered immune systems also have increased risk of developing HPV-related cancers.

How is it prevented?

HPV infection and therefore cervical cancer can be prevented by vaccination. There are now two FDA vaccines approved for males and females between ages nine and 26, and according to the latest recommendations from the CDC, all children between nine and 13 should complete the vaccine series. Children younger than 15 should receive two doses of the vaccine six months apart and those over age 15 should complete a three-dose series. Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey is joining with the nation’s 68 other National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers in supporting these newly revised recommendations. Keep in mind, for a woman, vaccination does NOT mean she should refrain from receiving a routine gynecological screening known as a Pap smear since the vaccine does not 100 percent guarantee against the development of cervical cancer.

How is it detected?

Pap smears detect precancerous changes that occur in cells and also can now test for HPV infection. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women begin annual screening for cervical cancer at age 21. A woman should consult with her doctor about the frequency of screening, as it depends on age, results from prior testing, and other health factors.Symptoms are also important for detection. These can include abnormal vaginal bleeding, discharge, bleeding after intercourse, or back pain. A woman should seek care if she develops any of these warning signs as well as maintain routine and appropriate screenings with her gynecologist.

How is it treated?

Precancerous changes of the cervix are treated with simple procedures. Treatment can prevent precancerous changes from becoming cervical cancer. Early stage cervical cancer is curable with surgery.

Remember, by quitting smoking, vaccinating against HPV, undergoing regular Pap smears and protecting yourself against sexually-transmitted diseases, you can help reduce your risk to developing cervical cancer.

Ruth Stephenson, DO, is a gynecologic oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.