News

Newswise — (NEW YORK —)

Funding and publication of gun violence research are disproportionately low compared to other leading causes of death in the United States, according to new research from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai published online today in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The study also determined that over a ten-year period, in relation to mortality rates, gun violence was the least-researched cause of death and the second-least funded cause of death, after falls.

Researchers analyzed mortality statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2004 to 2014 to determine the top 30 causes of death in the U.S. Findings indicated that gun violence killed about as many people as sepsis; however, funding for gun violence research was about 0.7% of that for sepsis, and publication volume was about 4%.

“We’re spending and publishing far less than what we ought to be based on the number of people who are dying,” said David E. Stark, MD, MS, Assistant Professor, Department of Health System Design and Global Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and lead author of the study. “Research is the first stop on the road to public health improvement, and we’re not seeing that with gun violence the way we did with automobile deaths.”

More than 30,000 people die each year from gun violence in the U.S., a higher rate of death than any industrialized country in the world. Historically, research on gun violence has been limited in the U.S., mainly due to language inserted in a 1996 congressional appropriations bill that states, “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” Although the legislation does not ban gun-related research outright, funding remains anemic for the research community.

“Dr. Stark’s research is important because the data is compelling; gun violence had less funding and fewer publications than comparable injury-related causes of death including motor vehicle accidents and poisonings,” said Prabhjot Singh, MD, PhD, Chair, Department of Health System Design and Global Health, Icahn School of Medicine. “We know that gun violence disproportionately affects vulnerable communities, including young people, and inflicts many more nonfatal injuries than deaths. As a result, we suspect the magnitude of this disparity in research funding, when considering years of potential life lost or lived with disability, is even greater,” said Dr. Singh.

Additional study collaborators include Nigam H. Shah, M.B.B.S., PhD, of the Stanford University School of medicine, Stanford, California. The research was supported by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number T15LM007033.

About the Mount Sinai Health SystemThe Mount Sinai Health System is an integrated health system committed to providing distinguished care, conducting transformative research, and advancing biomedical education. Structured around seven hospital campuses and a single medical school, the Health System has an extensive ambulatory network and a range of inpatient and outpatient services—from community-based facilities to tertiary and quaternary care.

The System includes approximately 7,100 primary and specialty care physicians; 12 joint-venture ambulatory surgery centers; more than 140 ambulatory practices throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, Long Island, and Florida; and 31 affiliated community health centers. Physicians are affiliated with the renowned Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is ranked among the highest in the nation in National Institutes of Health funding per investigator. The Mount Sinai Hospital is on the “Honor Roll” of best hospitals in America, ranked No. 15 nationally in the 2016-2017 “Best Hospitals” issue of U.S. News & World Report. The Mount Sinai Hospital is also ranked as one of the nation’s top 20 hospitals in Geriatrics, Gastroenterology/GI Surgery, Cardiology/Heart Surgery, Diabetes/Endocrinology, Nephrology, Neurology/Neurosurgery, and Ear, Nose & Throat, and is in the top 50 in four other specialties. New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai is ranked No. 10 nationally for Ophthalmology, while Mount Sinai Beth Israel, Mount Sinai St. Luke's, and Mount Sinai West are ranked regionally. Mount Sinai’s Kravis Children’s Hospital is ranked in seven out of ten pediatric specialties by U.S. News & World Report in "Best Children's Hospitals."

For more information, visit http://www.mountsinai.org/, or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

# # #

Newswise —

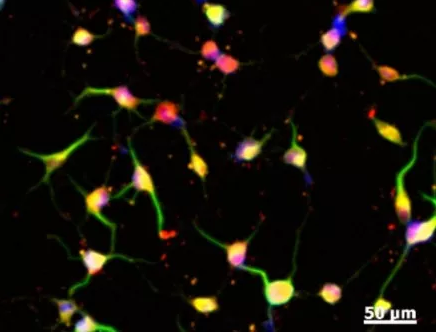

Researchers from North Carolina State University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University have developed a synthetic version of a cardiac stem cell. These synthetic stem cells offer therapeutic benefits comparable to those from natural stem cells and could reduce some of the risks associated with stem cell therapies. Additionally, these cells have better preservation stability and the technology is generalizable to other types of stem cells.

Stem cell therapies work by promoting endogenous repair; that is, they aid damaged tissue in repairing itself by secreting “paracrine factors,” including proteins and genetic materials. While stem cell therapies can be effective, they are also associated with some risks of both tumor growth and immune rejection. Also, the cells themselves are very fragile, requiring careful storage and a multi-step process of typing and characterization before they can be used.

Ke Cheng, associate professor of molecular biomedical sciences at NC State University, associate professor in the joint biomedical engineering program at NC State and UNC and adjunct associate professor at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, led a team in developing the synthetic version of a cardiac stem cell that could be used in off-the-shelf applications.

Cheng and his colleagues fabricated a cell-mimicking microparticle (CMMP) from poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) or PLGA, a biodegradable and biocompatible polymer. The researchers then harvested growth factor proteins from cultured human cardiac stem cells and added them to the PLGA. Finally, they coated the particle with cardiac stem cell membrane.

“We took the cargo and the shell of the stem cell and packaged it into a biodegradable particle,” Cheng says.

When tested in vitro, both the CMMP and cardiac stem cell promoted the growth of cardiac muscle cells. They also tested the CMMP in a mouse model with myocardial infarction, and found that its ability to bind to cardiac tissue and promote growth after a heart attack was comparable to that of cardiac stem cells. Due to its structure, CMMP cannot replicate – reducing the risk of tumor formation.

“The synthetic cells operate much the same way a deactivated vaccine works,” Cheng says. “Their membranes allow them to bypass the immune response, bind to cardiac tissue, release the growth factors and generate repair, but they cannot amplify by themselves. So you get the benefits of stem cell therapy without risks.”

The synthetic stem cells are much more durable than human stem cells, and can tolerate harsh freezing and thawing. They also don’t have to be derived from the patient’s own cells. And the manufacturing process can be used with any type of stem cell.

“We are hoping that this may be a first step toward a truly off-the-shelf stem cell product that would enable people to receive beneficial stem cell therapies when they’re needed, without costly delays,” Cheng says.

The research appears in the journal Nature Communications. Cheng is corresponding author. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, NC State Chancellor’s Innovation Fund and University of North Carolina General Assembly Research Opportunities Initiative grant. The co-first authors of this paper are. Junnan Tang, Deliang Shen, and Thomas Caranasos. Cheng’s collaborators are Quancheng Kan and Jinying Zhang at The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Henan, China.

-peake-

Note to editors: An abstract of the paper follows.

“Therapeutic microparticles functionalized with biomimetic cardiac stem cell membranes and secretome”

DOI: 10.1038/NCOMMS13724

Authors: Junnan Tang, Deliang Shen, Thomas George Caranasos, Zegen Wang, Tyler A. Allen, Adam Vandergriff, Michael Taylor Hensley, Phuong-Uyen Dinh, Jhon Cores, Taosheng Li, Jinying Zhang, Quancheng Kan, Ke Cheng

Published: Dec. 26, 2016 in Nature Communications

Abstract: Stem cell therapy represents a promising strategy in regenerative medicine. However, cells need to be carefully preserved and processed before usage. In addition, cell transplantation carries immunogenicity and/or tumorigenicity risks. Mounting lines of evidences indicate that stem cells exert their beneficial effects mainly through secretion (of regenerative factors) and membrane-based cell-cell interaction with the injured cells. Herein, we fabricated a synthetic cell-mimicking microparticle (CMMP) that recapitulates stem cell functions in tissue repair. CMMPs carries similar secreted proteins and membranes as genuine cardiac stem cells do. In a mouse model of myocardial infarction, injection of CMMPs leads to preservation of viable myocardium and augmentation of cardiac functions similar to cardiac stem cell therapy. CMMPs (derived from human cells) do not stimulate T cells infiltration in immuno-competent mice. In conclusion, CMMPs act as “synthetic stem cells” which mimic the paracrine and biointerfacing activities of natural stem cells in therapeutic cardiac regeneration.

Newswise — BIRMINGHAM, Ala. –

Many people start the new year with a list of lofty goals for self-improvement, but statistics say most of the 45 percent of Americans who typically make resolutions don’t keep them all year long. In fact, according to the Statistic Brain Research Institute, only 8 percent of Americans who make resolutions are successful in achieving them, and other studies suggest that 80 percent of people will abandon those resolutions by February.

The No. 1 resolution on most lists? Losing weight. But even though statistics say resolutions do not typically yield results, they can still be worthwhile .

According to UAB Director of Employee Wellness Anna Threadcraft, RDN, there are four ways in which people can manage expectations of being healthy and keep their New Year’s resolutions:

•Start Small: When it comes to making health goals, start small. Begin incorporating small, sustainable changes into your lifestyle that you can stick with, not just the ones that sound good but you know you’ll never maintain.

•Plan Ahead: Whether you’re married or single, your first date in 2017 needs to be with your grocery story. It’s much easier to make wise choices if you have healthy options readily available.

•Be Accountable: A lot of people fall off the wellness wagon within a few short weeks after setting goals, so set yourself up for success. Place a reminder or check-in on your phone, or send a prescheduled email to yourself. Include reminders of why you’re working on the goals, and ask yourself the questions you know you want to confidently answer when the reminder comes through.

•Rest: We underestimate the simple power of being rested. Before you start making any huge health changes that require great effort, consider your sleeping patterns. There may be room for some simple improvement that goes a long way. Changes might include making a point to get more sleep in general, or working on improving the quality of what you already get. When you are well-rested, you make better decisions, plan better and typically embrace life with a better attitude all the way around.

But many people do not focus just on physical health. UAB clinical psychologist Josh Klapow, Ph.D., says people should focus on mental wellness as well.

“Our thoughts and feelings have a direct impact on our overall well-being,” he said.

Klapow says taking hold of stress can have a lasting impact on mental wellness.

“Daily stresses have a funny way of building up to a point where people can feel overwhelmed,” he said. “Stressful situations can’t always be stopped, but there are ways to manage the feelings of stress.”

Klapow suggests writing down those stressful situations and putting checkmarks next to the ones that can be changed.

“Monitoring stress levels is a good habit to make, and taking short mental breaks can be helpful in breaking up the high-tension moments,” Klapow said. “Carving out a little time for something as simple as a daily walk can also reduce feelings of stress.”

Threadcraft and Klapow agree that having a plan to move forward, setting specific goals and keeping track of progress are great action items to keep in mind when heading toward the new year.

Newswise — (Cambridge, Mass.) —

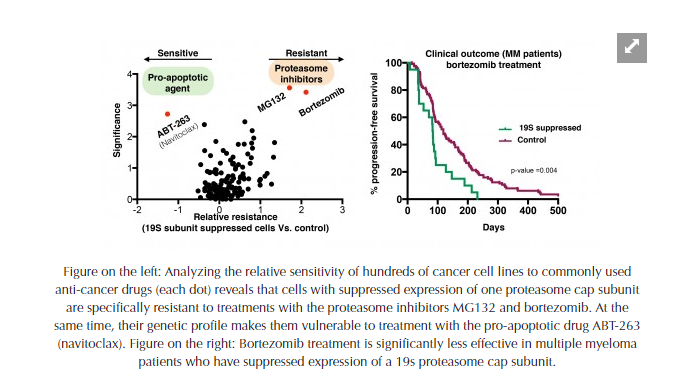

The use of proteasome inhibitors to treat cancer has been greatly limited by the ability of cancer cells to develop resistance to these drugs. But Whitehead Institute researchers have found a mechanism underlying this resistance—a mechanism that naturally occurs in many diverse cancer types and that may expose vulnerabilities to drugs that spur the natural cell-death process.

This finding—which also identifies a biomarker that can be used to gain a deeper understanding of the proteasome inhibitor-resistant state— is reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in an article entitled, Suppression of 19S proteasome subunits marks emergence of an altered cell state in diverse cancers.

Proteasomes are large protein complexes that mediate protein degradation and play a crucial role in maintaining protein equilibrium within the cell. When cells become cancerous, tremendous stresses are placed on the cellular machinery responsible for maintaining protein equilibrium—and that machinery is the target of anti-cancer drugs called proteasome inhibitors. Although proteasome inhibitors are very efficient in selective killing of cancer tumor cells grown in a dish (in-vitro), their success in the clinic has largely been undermined by the development of resistance—mechanisms of which are poorly understood.

“However, recently, we discovered a counterintuitive mechanism by which cells can acquire resistance to proteasome inhibitors in vitro,” explains Peter Tsvetkov, lead author of the PNAS article and a post-doctoral researcher at Whitehead Institute. “Now, in this report, we show that this mechanism is at work in many human cancers. Moreover, we have determined that the mechanism is symptomatic of a broadly altered state in the cell, with a unique gene signature and newly exposed vulnerabilities that can be targeted with existing drugs.” Notably, the mechanism was clearly associated with poor outcome in patients with the blood cancer myeloma, where proteasome inhibitors are a mainstay of treatment.

Analyzing data from thousands of cancer lines and tumors, the researchers found that those demonstrating resistance to proteasome inhibitor drugs were marked by suppressed expression of one or more of the cells’ proteasome cap subunits (which are a subsets of the larger proteasome). Suppressing the expression of even one of the many subunits making up the cap will impair the assembly of the whole cap, resulting in a proteasome-inhibitor resistant state. “This fact reinforces just how complex the mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapy can be,” says Luke Whitesell, a senior author of the PNAS paper and senior scientist at Whitehead Institute

Nevertheless, this new report reveals a strategy to address such resistance which may have broad utility. The researchers found that, beyond conferring resistance to proteasome inhibitors, the suppressed expression of proteasome subunits reflects a broad remodeling of the cell’s gene signature. Furthermore, this can also serve as a biomarker to stratify patients for treatment. “That signature marks a heritably altered and therapeutically relevant state in diverse cancers—a state that may expose vulnerability to specific drugs that are already in use in the clinic,” Tsvetkov observes. “Cancers can achieve this resistance by multiple mechanisms, genetic or epigenetic. But these findings point us to new strategies and novel compounds that can be developed as treatments that will be more effective for an array of cancer types because they are less susceptible to the emergence of resistance.”

This work was supported by EMBO fellowship ALTF 739-2011 and the Charles A. King trust postdoctoral fellowship program.

Written by Merrill S. Meadow

* * *

Luke Whitesell is Senior Science at Whitehead Institute.

Peter Tsvetkov is a post-doctoral researcher at Whitehead Institute.

* * *

Full Citation:

Suppression of 19S proteasome subunits marks emergence of an altered cell state in diverse cancers

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, online publication: Dec. 26, 2016

Peter Tsvetkov*,1, Ethan Sokol1,2, Dexter Jin1,2, Zarina Brune1, Prathapan Thiru1, Mahmoud Ghandi3, Levi A. Garraway3,4,5, Piyush Gupta1,2,6,7, Sandro Santagata8, Luke Whitesell1, Susan Lindquist **,1,2,9,

1 Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA, 02142 2 Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA3 Broad Institute, 415 Main St. Cambridge, MA 021424 Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA5 Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 6 Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Cambridge, MA7 Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Cambridge, MA 021388 Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA9 HHMI, Department of Biology, MIT, Cambridge MA 02139* Corresponding author**Deceased

Whitehead Institute is a world-renowned non-profit research institution dedicated to improving human health through basic biomedical research. Wholly independent in its governance, finances, and research programs, Whitehead shares a close affiliation with Massachusetts Institute of Technology through its faculty, who hold joint MIT appointments.

Newswise —

Human papillomavirus-positive oropharynx cancers (cancers of the tonsils and back of the throat) are on rise. After radiation treatment, patients often experience severe, lifelong swallowing, eating, and nutritional issues. However, new clinical trial research shows reducing radiation for some patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas can maintain high cure rates while sparing some of these late toxicities.

“We found there are some patients have very high cure rates with reduced doses of radiation,” said Barbara Burtness, MD, Professor of Medicine (Medical Oncology), Yale Cancer Center, Disease Research Team Leader for the Head and Neck Cancers Program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, and the chair of the ECOG-ACRIN head and neck committee. “Radiation dose reduction resulted in significantly improved swallowing and nutritional status,” she said.

The study, published in the December 26 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology, showed that patients treated with reduced radiation had less difficulty swallowing solids (40 percent versus 89 percent of patients treated with standard doses of radiation) or impaired nutrition (10 percent versus 44 percent of patients treated with regular doses of radiation).

“Today, many younger patients are presenting with HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx,” said Dr. Burtness. “And while traditional chemoradiation has demonstrated good tumor control and survival rates for patients, too often they encounter unpleasant outcomes that can include difficulty swallowing solid foods, impaired nutrition, aspiration and feeding tube dependence,” said Dr. Burtness. “Younger patients may have to deal with these side effects for decades after cancer treatment. We want to help improve our patients’ quality of life.”

The study included 80 patients from 16 ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group sites who had stage three or four HPV-positive squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, and were candidates for surgery. Eligible patients received three courses of induction chemotherapy with the drugs cisplatin, paclitaxel, and cetuximab. Patients with good clinical response then received reduced radiation.

Study results also showed that patients who had a history of smoking less than 10 packs of cigarettes a year had a very high disease control compared with heavy smokers.

Newswise —

In a research letter published Dec. 27, 2016, in JAMA, University of Chicago physicians describe a new concern for patients in the hospital: distractions caused by the misfortune of other patients.

The researchers found that when one patient on a typical 20-bed hospital unit took a turn for the worse – a cardiac arrest, for example, or being transferred to an intensive-care unit – the other patients on that ward were at increased risk for their own setbacks.

In the six hours after a critical-illness event, the odds that a second patient in the same unit would undergo a comparable crisis increased by about 18 percent. If there were two such events during a six-hour time period, the risk of yet another occurrence went up by about 53 percent. Risks were slightly higher when the initial critical illness events occurred at night.

Cardiac arrests, urgent ICU transfers or patient deaths were also associated with delayed discharge from the hospital for the other patients on the same unit.

“This should serve as a wake-up call for hospital-based physicians,” said study author Matthew Churpek, MD, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

“Our data suggests that after caring for a patient who becomes critically ill on the hospital wards, we should routinely check to see how the other patients on the unit are doing,” Churpek said.

“Following these high-intensity events, our to-do list should include a thorough assessment of the other patients on the unit, to make sure none of them are at risk of slipping through the cracks.” Luckily, such events were relatively rare. Nearly 84,000 adult patients were admitted to non-ICU beds at the University of Chicago Medicine from 2009 to 2013. About five percent of those patients were subsequently transferred to an intensive-care unit (4,107) or experienced an in-hospital cardiac arrest (179).

Patients who had a cardiac arrest or required ICU transfer tended to be a few years older and male. They had been in the hospital, on average, for 13 days, four times longer than patients who did not have a critical-illness event.

“We suspected this phenomenon based on our own anecdotal experience,” said co-author Samuel Volchenboum, MD, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago and director of the University’s Center for Research Informatics. “But until we had access to a large, well-curated research-data warehouse, we couldn’t perform a study like this.”

“Very few academic centers have access to the kinds of high-quality data needed to perform this type of investigation,” he added.

The study was designed to detect and quantify any increased risk to neighboring patients. The researchers speculate that one potential factor may be that doctors and nurses could have been “temporarily diverted to help care for critically ill patients,” Volchenboum said. “Further study is needed to determine the causes of this effect.”

The study was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Additional authors were Anoop Mayampurath, Gözde Göksu-Gürsoy, Dana P. Edelson and Michael D. Howell, all from the University of Chicago.

Newswise —

Emergency rooms in communities with indoor smoking bans reported a 17 percent decrease in the number of children needing care for asthma attacks, according to new research from the University of Chicago Medicine.

The study, led by pediatric allergy expert Christina Ciaccio, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago, examined 20 metropolitan areas around the country that introduced clean indoor air regulations prohibiting smoking in public places such as restaurants, hotels and workplaces. The study, co-authored by researchers from Brown University and Kansas University, was published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

“Children are in a very unique situation in that they have very little control over their environment,” Ciaccio said, adding that changing public policies is one way to help control the environment for children in public spaces. “This study shows that even those short exposures to secondhand smoke in public spaces like restaurants can have a significant impact on asthma exacerbations.”

The researchers reviewed asthma-related emergency department visits that occurred between July 2000 and January 2014. The data came from 20 hospitals in 14 different states and the District of Columbia. For each hospital, the researchers counted the number of visits during the three years before and the three years after indoor smoking bans took effect.

“Combined with other studies, our results make it clear that clean indoor air legislation improves public health,” said study co-author Theresa Shireman, PhD, professor in the Brown University School of Public Health.

All told, the team reviewed data from 335,588 emergency room visits. When making pre-ban and post-ban comparisons, they controlled for a variety of possible factors including seasonality and things like patient gender, age, race and socioeconomic status.

Results varied by community, but declined in the majority of locales. In the aggregate across all 20 hospitals, the reduction in ER visits became deeper with every passing year following the bans. Children’s ER visits fell 8 percent after one year, 13 percent after two years and, finally, 17 percent after three years.

The researchers also found there was no general, nationwide decline in children's asthma-related emergency room visits beyond those seen in communities with the smoking bans. The researchers acknowledged the study only shows an association and doesn’t prove the bans caused the drop in emergency room visits, but Shireman said the evidence strongly suggests it.

“We should all breathe easier when our children do,” said Tami Gurley-Calvez, PhD, associate professor of health policy and management at Kansas University and the paper’s third author.

The paper was titled “Indoor tobacco legislation is associated with fewer emergency department visits for asthma exacerbation in children.”

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — ANN ARBOR, Mich. -

“Why does a 30-year-old hit their foot against the curb in the parking lot and take a half step and recover, whereas a 71-year-old falls and an 82-year-old falls awkwardly and fractures their hip?” asks James Richardson, M.D., professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Musculoskeletal Center.

For the last several years, Richardson and his team set out to answer these questions, attempting to find which specific factors determine whether, and why, an older person successfully recovers from a trip or stumble. All this in an effort to help prevent the serious injuries, disability, and even death, that too often follow accidental falls.

“Falls research has been sort of stuck, with investigators re-massaging over 100 identified fall ‘risk factors,’ many of which are repetitive and circular,” Richardson explains. “For example, a 2014 review lists the following three leading risk factors for falls: poor gait/balance, taking a large number of prescription medications and having a history of a fall in the prior year.”

Richardson continues, “If engineers were asked why a specific class of boat sank frequently and the answer came back: poor flotation and navigational ability, history of sinking in the prior year and the captain took drugs, we would fire the engineers! Our goal has been to develop an understanding of the specific, discrete characteristics that are responsible for success after a trip or stumble while walking, and to make those characteristics measurable in the clinic.”

Richardson’s latest research finds that it’s not only risk factors like lower limb strength and precise perception of the limb’s position that determine if a geriatric patient will recover from a perturbation, but also complex and simple reaction times, or as he prefers to refer to it, a person’s “brain speed.” The work is published in the January 2017 edition of the American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation.

“Our study wanted to identify relationships between complex and simple clinical measures of reaction time and indicators of balance in elderly subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, nerve damage that can occur in those with diabetes,” Richardson says.

“These patients fall twice as often as people their age typically do, so we wanted to examine each person’s ability to make a decision in less than half a second, or around 400 milliseconds. Importantly, this is also about the length of time the foot is in the air before landing while walking, and about the time available to recover from a stumble or trip.”

He realized they needed a new, easy way to measure that rapid decision-making ability.

Measuring simple and complex reaction time

Using a device developed with U-M co-inventors James T. Eckner, Hogene Kim and James A. Ashton-Miller, simple reaction time is measured much like a drop-ruler test used in many school science classes, but is a bit more standardized.

“The clinical reaction time assessment device consists of a long, lightweight stick attached to a rectangular box at one end. The box serves as a finger spacer to standardize initial hand position and finger closure distance, as well as a housing for the electronic components of the device,” Richardson says.

To measure simple reaction time, the patient or subject sits with the forearm resting on a desk with the hand off the edge of the surface. The examiner stands and suspends the device with the box hanging between the subject’s thumb and other fingers and lets the device drop at varying intervals. The subject catches it as quickly as possible and the device provides a display of the elapsed time between drop and catch, which serves as a measurement of simple reaction time.

Although measuring simple reaction time is useful, Richardson says that the complex reaction time accuracy has been more revealing. The initial set up of the device and subject is the same. However, in this instance, the subject’s task is to catch the falling device only during the random 50 percent of trials where lights attached to the box illuminate at the moment the device is dropped, and to resist catching it when the lights do not illuminate.

“Resisting catching when the lights don’t go off is the hard part,” Richardson says. “We all want to catch something that is falling. The subject must perceive light illumination status and then act very quickly to withhold the natural tendency to catch a falling object.”

In the study, Richardson and team used the device with a sample of 42 subjects, 26 with diabetic neuropathy and 16 without, with an average age of 69.1 years old, to examine their complex reaction time accuracy and their simple reaction time latency, in addition to the usual measures of leg strength and perception of motion.

They then looked to see how well these measures predicted one-legged balance time, the ability to control step width when walking on a hazardous uneven surface in the research lab and major fall-related injuries over the next 12 months.

Examining the results

In the subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, good complex reaction time accuracy and quick simple reaction time were strongly associated with a longer one-legged balance time, and were the only predictors of good control of step width on the uneven surface. In addition, they appeared to identify those who sustained major fall-related injury during the one-year follow up. Surprisingly, the measures of leg strength and motion perception had no influence on step width control on the hazardous surface and did not appear to predict major injury.

“Essentially we found that those who were able to grab the device quickly, or quickly make the decision to let it drop, had quick brains that were somehow helping them stay balanced and avoid aberrant steps on the uneven surface,” Richardson says.

He explains that the ability to avoid aberrant steps after hitting a bump while walking, and stay balanced while performing the trials, were likely based on the participant’s brain processing speed. In particular, the ability to quickly withhold, or inhibit, a planned movement is required for good complex reaction accuracy and responding to a perturbation while walking. In both cases, the original plan of action must be aborted and a new one substituted within approximately a 400 milliseconds time interval.

“With this in mind, it makes perfect sense that brains fast enough to have good complex reaction time accuracy were also fast enough to quickly pay attention to the perturbation while walking, inhibit the step that was planned and quickly execute a safer alternative,” Richardson says. “The faster your brain can oscillate between various external stimuli, or events, and your own internal thinking clutter, the better off you are. When an elderly person falls, it seems likely that their brain is not keeping up with what is happening and so it is not able to quickly, and selectively, attend to a particular stimulus, such as hitting a curb.”

Richardson says this assessment, which cannot be produced from a computer or pen/pencil tests, could be valuable to other health care providers, such as primary care physicians, neurologists, geriatricians and a variety of rehabilitation professionals.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

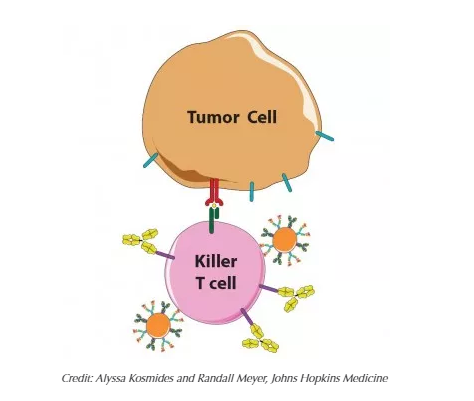

By combining two treatment strategies, both aimed at boosting the immune system's killer T cells, Johns Hopkins researchers report they lengthened the lives of mice with skin cancer more than by using either strategy on its own. And, they say, because the combination technique is easily tailored to different types of cancer, their findings -- if confirmed in humans -- have the potential to enhance treatment options for a wide variety of cancer patients.

"To our knowledge, this was the first time a 'biomimetic,' artificial, cell-like particle -- engineered to mimic an immune process that occurs in nature -- was used in combination with more traditional immunotherapy," says Jonathan Schneck, M.D., Ph.D., professor of pathology, who led the study together with Jordan Green, Ph.D., associate professor of biomedical engineering, both of whom are also members of the Kimmel Cancer Center.

A summary of their study results will be published in the February issue of the journal Biomaterials.

Scientists know the immune system is a double-edged sword. If it's too weak, people succumb to viruses, bacteria and cancer; if it's too strong, they get allergies and autoimmune diseases, like diabetes and lupus. To prevent the immune system's killer T cells from attacking them, the body's own cells display the protein PD-L1, which "shakes hands" with the protein PD-1 on T cells to signal they are friend, not foe.

Unfortunately, many cancer cells learn this handshake and display PD-L1 to protect themselves. Once scientists and drugmakers figured this out, cancer specialists began giving their patients a recently developed class of immunotherapy drugs including a protein, called anti-PD-1, a so-called checkpoint inhibitor, that blocks PD-1 and prevents the handshake from taking place.

PD-1 blockers have been shown to extend cancer survival rates up to five years but only work for a limited number of patients: between 15 to 30 percent of patients with certain types of cancer, such as skin, kidney and lung cancer. "We need to do better," says Schneck, who is also a member of the Institute for Cell Engineering.

For the past several years, Schneck says, he and Green worked on an immune system therapy involving specialized plastic beads that showed promise treating skin cancer, or melanoma, in mice. They asked themselves if a combination of anti-PD1 and their so-called biomimetic beads could indeed do better.

Made from a biodegradable plastic that has been FDA-approved for other applications and outfitted with the right proteins, the tiny beads interact with killer T cells as so-called antigen-presenting cells (APCs), whose job is to "teach" T cells what threats to attack. One of the APC proteins is like an empty claw, ready to clasp enemy proteins. When an untrained T cell engages with an APC's full claw, that T cell multiplies to swarm the enemy identified by the protein in the claw, Schneck explains.

"By simply bathing artificial APCs in one enemy protein or another, we can prepare them to activate T cells to fight specific cancers or other diseases," says Green, who is also part of the Institute for NanoBioTechnology, which is devoted to the creation of such devices at Johns Hopkins.

To test their idea for a combined therapy, the scientists first "primed" T cells and tumor cells to mimic a natural tumor scenario, but in a laboratory setting. In one tube, the scientists activated mouse T cells with artificial APCs displaying a melanoma protein. In another tube, they mixed mouse melanoma cells with a molecule made by T cells so they would ready their PD-L1 defense. Then the scientists mixed the primed T cells with primed tumor cells in three different ways: with artificial APCs, with anti-PD-1 and with both.

To assess the level of T cell activation, they measured production levels of an immunologic molecule called interferon-gamma. T cells participating in the combined therapy produced a 35 percent increase in interferon-gamma over the artificial APCs alone and a 72 percent increase over anti-PD-1 alone.

The researchers next used artificial APCs loaded with a fluorescent dye to see where the artificial APCs would migrate after being injected into the bloodstream. They injected some mice with just APCs and others with APCs first mixed with T cells.

The following day, they found that most of the artificial APCs had migrated directly to the spleen and liver, which was expected because the liver is a major clearing house for the body, while the spleen is a central part of the immune system. The researchers also found that 60 percent more artificial APCs found their way to the spleen if first mixed with T cells, suggesting that the T cells helped them get to the right spot.

Finally, mice with melanoma were given injections of tumor-specific T cells together with anti-PD-1 alone, artificial APCs alone or anti-PD-1 plus artificial APCs. By tracking blood samples and tumor size, the researchers found that the T cells multiplied at least twice as much in the combination therapy group than with either single treatment. More importantly, they reported, the tumors were about 30 percent smaller in the combination group than in mice that received no treatment. The mice also survived longest in the combination group, with 45 percent still alive at day 20, when all the mice in the other groups were dead.

"This was a great indication that our efforts at immunoengineering, or designing new biotechnology to tune the immune system, can work therapeutically," says Green. "We are now evaluating this dual strategy utilizing artificial APCs that further mimic the shapes of immune cells, such as with football and pancake shapes based on our previous work, and we expect those to do even better."

Other authors of the report include Alyssa Kosmides, Randall Meyer, John Hickey, Kent Aje and Ka Ho Nicholas Cheung of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI072677, AI44129), the National Cancer Institute (CA108835, R25CA153952, 2T32CA153952-06, F31CA206344), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01-EB016721), the Troper Wojcicki Foundation, the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins, the JHU-Coulter Translational Partnership, the JHU Catalyst and Discovery awards programs, the TEDCO Maryland Innovation Initiative, the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists, the National Science Foundation (DGE-1232825), and sponsored research agreements with Miltenyi Biotec and NexImmune.

Under a licensing agreement between NexImmune and The Johns Hopkins University, Jonathan Schneck is entitled to a share of royalty received by the university on sales of products derived from this article. Jordan Green is on the scientific advisory board for NexImmune. The terms of these arrangements are being managed by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Newswise — MANHATTAN, Kan. —

An important part of holiday meal-planning is deciding which high-calorie foods to splurge on and which not to invite onto the plates, according to a Kansas State University researcher.

Sam Emerson, doctoral student in food, nutrition, dietetics and health, Midlothian, Texas, offers tips for battling overindulgence of holiday treats.

Emerson's No. 1 piece of advice for people trying to maintain weight and stay healthy over the holidays is to have a plan before they are faced with a buffet or table full of options.

"Eating food that is not nutritious is commonly part of celebrating, but it can become problematic if we make no effort to curb the splurging," Emerson said. "We need to go in with a plan for how active we're going to be, how much we're going to eat, and whether we'll allow ourselves dessert. That way, you can know later to not eat a second piece of pie because you already ate the one piece of pie you were going to have."

Emerson advocates moderation rather than strict avoidance because typically even if people plan to not eat dessert, they usually end up partaking. At that point, their "all or nothing" mentality switches to "all" and the floodgates open for seconds and thirds.

Emerson, who specializes in post-meal metabolism research, said some desserts will impact your waistline more than others. Pecan pie is the heftiest of the traditional Christmas pies. A one-eighth piece, which is a small sliver, is about 500 calories. In comparison, the same size slice of pumpkin pie is 320 calories. Sweet potato pie is the least calorically dense, weighing in at just under 300 calories, Emerson said.

To avoid saving room for dessert, Emerson advises loading your plate with green beans, salad or other plant-based offerings. He said the evidence is clear that if you fill your plate with vegetables first, you will eat up to 10 percent fewer calories overall.

Non-dessert dishes and drinks that are calorically dense include stuffing, mashed potatoes and eggnog. According to Emerson, a standard 1-cup serving of stuffing has 350 calories; a cup of mashed potatoes has nearly 250 calories; and eggnog has about 450 calories per cup.

"Many people don't drink just one cup," Emerson said. "If you drink two cups, that's nearly 1,000 calories, which is about half a moderately active person's recommended intake for the whole day."

Emerson advocates exercising to help balance caloric intake and output. He said research shows just one session of exercise up to 15 hours before a large, high-fat meal helps the body to healthfully digest the meal with fewer effects on glucose levels, blood lipids and inflammation.

"You could exercise in the morning, eat a really large meal that evening and still see benefits from your earlier exercise in terms of how your body processes the meal, which is pretty incredible," Emerson said.

Between meals, Emerson advises putting away sweets, like chocolates or cookies. Research shows that when food is readily available, people eat more than is best.

"If you leave sweets out where you'll walk past them several times a day, no matter how hard you try, you're going to grab that brownie every now and then," Emerson said.

Emerson also offers these tips:

• Don't skip meals. Some people avoid eating breakfast on Thanksgiving or skip dinner the night before a Christmas meal, thinking they are "saving up," but research shows they usually end up eating so many calories later at the larger meal that the calorie tally comes out to work against them.

• Wait after your first portion. Before going for seconds, spend 5-10 minutes talking to the people around you. After you socialize, see if you're still hungry.

"Overall, I recommend trying to focus on being with family and friends," Emerson said. "Eating is a part of the holidays, but if we aim to make it more about enjoying time with people and less about eating a lot, that can help us make more beneficial decisions for our health."